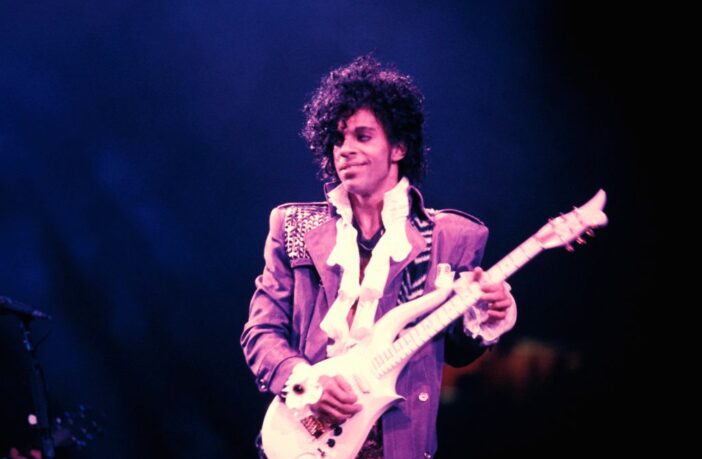

Source: Ebet Roberts / Getty

Forty years ago, Prince released Purple Rain to extraordinary acclaim. It was a stunning reception for a work that didn’t so much break the barrier that separates the sacred and the secular. It was more like he never acknowledged it; barriers were a foreign concept to Prince. And it’s not that he was the first to do it. The Black Diasporic Songbook is filled with revered artists, from Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, and Aretha Franklin, to Bob Marley, Marvin Gaye, and Lauryn Hill who too melded the sacred and the secular. But Prince was the first to do it and sell 13 million albums.

For generations, African American music and culture intentionally traversed two distinct lands. On one land God lived. On the other lived sex and all the temptations of man’s world. They were not meant to meet; their crossing of paths, a blasphemy.

We were the people who carried the ring-shout of Western and Central Africa across the long, terrible waters and crafted them into Negro spirituals sung by the brutally enslaved as they worked the blood-soaked fields of an emerging nation. Our songs, our spirituals, were patient and heart-shattering and yet somehow hopeful songs. There was a Promised Land and it was just there, just past the horizon. The power of that deep-spirit music / guide would travel us through the years and centuries, forever finding home long-past holy sounds made by those in chains. Mahalia Jackson and later, the Winans, Donnie McClurkin, Yolanda Adams.

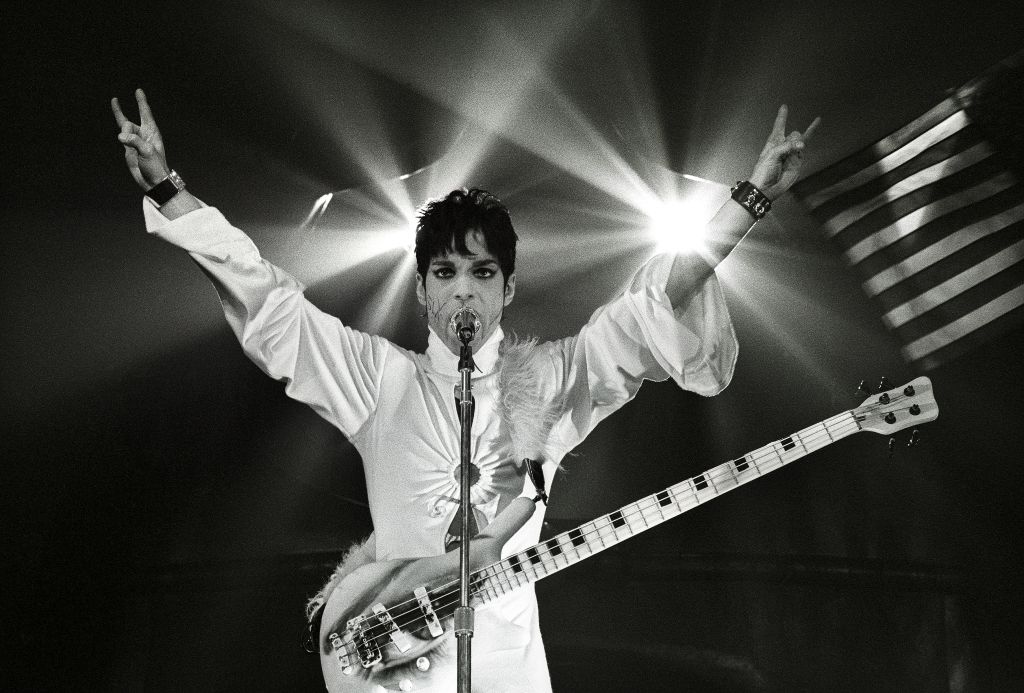

Source: Bob Sacha / Getty

Those prayers set to music were heard, were revered, but were not the sounds–at least not the lyrics of our more worldly selves. Those selves were secreted away mostly. They knew but kept silent about the booze and pheromone-soaked juke joints where the blues came down hard and the love and sex, all the harder. But that was the contained business of Saturday nights. We drank and kissed and we did more than on those nights but we prayed as hard as we played Come Sunday.

And in time, the walls that separated our Saturday nights from our Sunday mornings began to melt, if only a bit. Aretha may have taught a generation of brothers that if they wanted a do-right woman, they needed to be an all night man, but surrounded by her church family, she was Holy, Holy. That’s no criticism. It’s an observation, one about Prince.

He seemed to not notice or at least not be directed by the dichotomy of the secular and the sacred, the Heavenly and the Worldly all as one existence, all a singular plane. If we hadn’t noticed it before, Purple Rain brought that truth home in extraordinary fashion.

Source: Rob Verhorst / Getty

‘Purple Rain’ fuses rock, pop and funk with profound lyrical content that reflects a lineage that extends back to the spirituals, the gospels of the earliest African Methodist Episcopalian Churches. He weaves the sacred word and sound across a loom made of and by the living world of specific Black blues and not the blues gone long and gone far. The blues in Prince’s purple were all about the days here, the days now. And while he would not live to see the vicious murder of George Floyd, Prince knew that Minneapolis Goddamn all the same.

Listen again to “Let’s Go Crazy.” Prince sings,“if de-elevator tries to take you down, go crazy, punch a higher floor.” It was his call to arms for humanity in the war against the ultimate evil – Satan. In the song’s title track, Prince offers us “I only want to see you bathing in the purple rain.” It’s a baptism, a cleansing, a shedding of the former self for the new and higher self (this is wryly implied in the film Purple Rain where Prince’s character, The Kid, tells Apollonia to purify herself in the lake).

But in between “Let’s Go Crazy” and “Purple Rain” which bookend the album, there’s “Darling Nikki,” a recall of a brief and very worldly escapade with a kinky stranger. His compositions of innocent escapism, like “Take Me With U,” or else mournful self-examination, like “When Doves Cry,” “Darling Nikki” arrives unabashedly to celebrate hedonism. But he doesnt stay there long because just a few songs later is “I Would Die 4 U,” a representation of the three stations of the Cross. Each verse, respectively, embodies the Father/God, the Son/Christ, and the Holy Spirit.

Source: MARK RALSTON / Getty

Purple Rain not only represents a peak in Prince’s artistic career but serves as a testament to the enduring cultural and spiritual narrative that has always permeated Black music. But the intertwining of the sacred and the secular in Purple Rain highlights a transformative dialogue within Black music–and by extension, Black people. Navigating between the realms of earthly struggles and divine aspirations, Purple Rain created a space where personal and collective experiences converged in a transcendent artistic expression.

The sounds, the androgynous styling, the fluidity in presentation musically and beyond, no one was freer than Prince it seemed and we loved him for it. Loved him for daring us to love ourselves and just so freely, in the purple rain.

SEE ALSO:

Prince’s ‘Purple Rain’ Movie Is Being Turned Into A Stage Musical

Happy Birthday, Prince! 19 Surprising Facts To Know About ‘The Purple One’

8 photos