By Jessica Damiano,

The Associated Press

Women have long been at the forefront of gardening, whether passing agricultural traditions from generation to generation, organizing garden clubs and beautification societies, or — in some cases — making significant contributions to science and landscape design.

Some of these “plant women” gained notoriety for their work. Many are not as well known.

Here are a few who have left permanent marks on American horticultural history:

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer

(Photo courtesy of centerforlearnerequity.org)

A civil rights and agricultural activist, Hamer founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative in the late 1960s to provide land, livestock and vegetable-growing resources to poor Black families and farmers in Sunflower County, Mississippi. The Cooperative facilitated crop-sharing, self-reliance and financial independence. Participating families were also loaned a piglet to raise to maturity, after which they would return it for mating and give the cooperative two piglets from each litter to continue the program. “If you have a pig in your backyard, if you have some vegetables in your garden, you can feed yourself and your family, and nobody can push you around,” Hamer said. Her Cooperative became one of the earliest examples of modern community gardening and a precursor of today’s food justice movement.

Claudia ‘Lady Bird’ Johnson

Claudia ‘Lady Bird’ Johnso. (Photo courtesy of AP via Paul Cox/International Lady Bird Wildflower Center)

Claudia ‘Lady Bird’ Johnso. (Photo courtesy of AP via Paul Cox/International Lady Bird Wildflower Center)

First lady from 1963 to 1969, Johnson was an environmentalist and early native plants proponent who advocated for preserving wild spaces. She led the effort to secure the passage of the 1965 Highway Beautification Act during her husband’s presidency. The law sought to clear highways of billboards and to plant wildflowers along their shoulders to support plant and animal biodiversity and regional identity. Today, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at the University of Texas at Austin honors her legacy.

Marie Clark Taylor

Marie Clark Taylor

Marie Clark Taylor

(Courtesy of Fordham University)

In 1941, Taylor became the first Black woman to receive a doctorate in botany in the United States, and the first woman of any race to gain a Ph.D. in science from Fordham University. As an educator, she applied her doctoral research on the effect of light on plant growth to change the way high school science was taught. She encouraged the use of light microscopes and botanical materials in the classroom for the first time. In the mid-1960s, President Lyndon B. Johnson enlisted her to expand her teaching methods nationwide. Taylor also served as chair of Howard University’s Botany Department for nearly 30 years until her retirement in 1976.

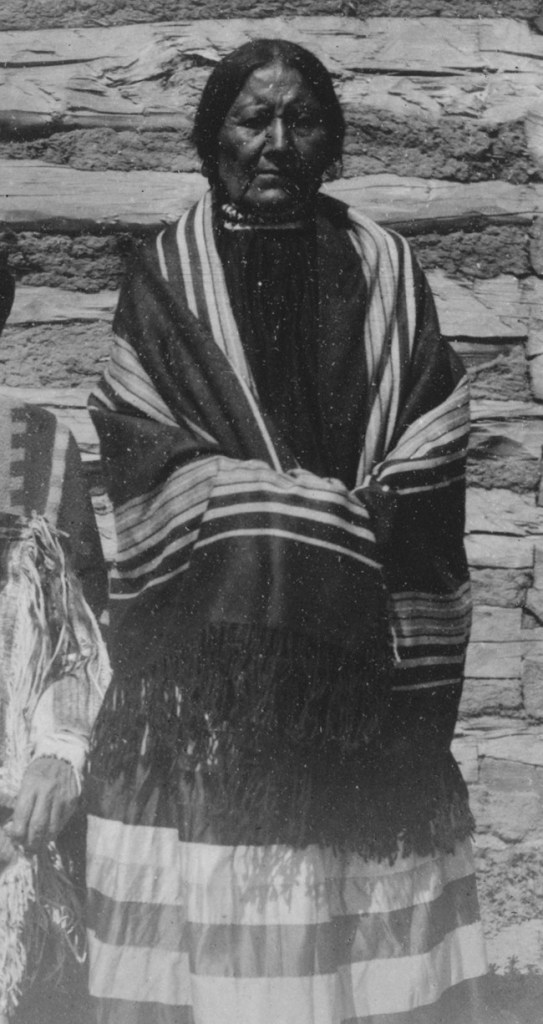

Waheenee (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

Waheenee (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

Waheenee

Also known as Buffalo Bird Woman, Waheenee was a Hidatsa woman born around 1839 in what is now North Dakota. She mastered and shared centuries-old cultivating, planting and harvesting techniques with Gilbert L. Wilson, a minister and anthropologist who studied the tribe in the early 1900s. During visits that spanned 10 years, Wilson, whose work was sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, transcribed Waheenee’s words with her son serving as interpreter. The resulting book, “Buffalo Bird Woman’s Garden: Agriculture of the Hidatsa Indians,” first published in 1917, documented the Hidatsa women’s methods for growing beans, corn, squash, sunflowers and tobacco, as well as the tools they used and their practices for drying and winter storage. Her advice is still relevant today.