By Ashleigh Fields

AFRO Assistant Editor

afields@afro.com

There are currently 49 seats in the James S. Brady briefing room for White House reporters dedicated to covering the most trying truths of our nation’s present and past. Only one belongs to a Black owned media outlet, well half a seat. The Grio, short for the griot, a term that references a separate class of people in West African culture designated as “oral historians” or “caretakers of the truth.” The entity stands in a league of its own surrounded by a sea of larger media companies and conglomerates. Across from them at the daily briefings stands history maker and trail blazer Karine Jean-Pierre who serves as the first Black press secretary for the President of the United States.

In November, she announced a pivotal decision to rename the lectern from which she unearths news for the American people, after two Black women, Alice Dunnigan and Ethel Payne.

“It’s been an honor and a privilege to serve as the first Black woman in this role. It’s not lost on me that I stand on the shoulders of Alice Dunnigan, Ethel Payne, and the monumental struggle and sacrifice of everyone who looks like me within, before, and beyond this White House,” Jean-Pierre told the AFRO. “It’s my hope that the Dunnigan-Payne lectern will serve as a beacon of what Black communicators can achieve – whether they are seated before it or answering questions behind it.”

The unique triangular structure is filled with uncommon features such as curved inward slants which showcase the speaker’s legs and feet. The object was fused with pieces of black walnut and metal.

“As you can see, the metal speaks to the resilience and strength of our nation, while the black walnut represents the rich history and the deep-rooted foundations upon which this country stands,” Jean-Pierre shared at unveiling during the Nov. 30 press briefing. “The blue paint signifies vigilance, perseverance, and justice.”

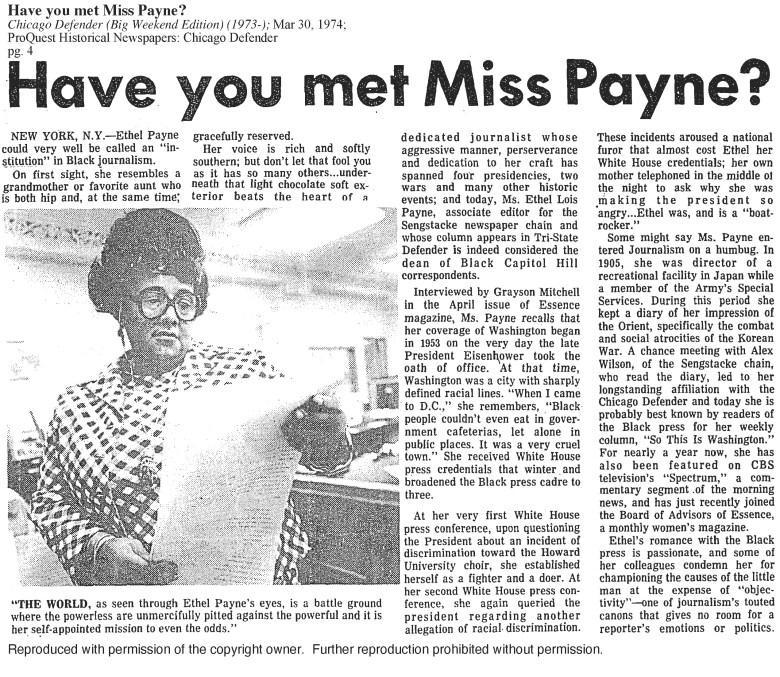

Payne and Dunnigan were the first Black women admitted to the White House Press core where they overcame remarkable challenges in their own right. The two co-authored many pieces together for the renowned Chicago Defender in which they bonded over tongue-lashings and shared traumas during presidential briefings.

“On February 10, 1954, I tried my-fledgling wings as an accredited White House reporter and asked President Eisenhower my first question at his news conferences,” Payne recalled in a Chicago Defender article she penned. “I remember my knees knocking and my voice quavering as Ike cupped a hand” to his ear and asked me to repeat.”

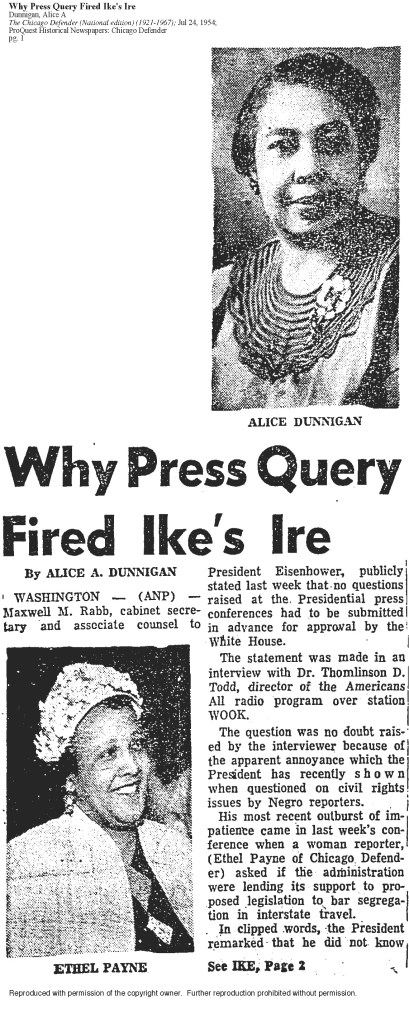

Over the weeks, a boldness began to develop and Payne quickly became known as the “First Lady of the Black Press” for her intense line of questioning based on research and lived experience. Dunnigan documented the most notorious bouts of anger seen by President Eisenhower in an article entitled, “Why Press Query Fired Ike’s Ire.”

“The President’s lack of knowledge on many racial issues, raised by reporters of Negro news- papers, seems to have become embarrassing after awhile, and his impatience began to show,” Dunnigan wrote. “The curt manner in which the President has begun answering the questions posed by Negro reporters has been observed and mentioned by many of the press and radio people present. It has also given rise to a critical “blast” issued upon the women reporters by the lone Negro man who attends the President’s conferences.”

“The disease of professional jealousy seems to be very contagious as it is apparently spreading to other male columnists who are joining the fray and vehemently tossing word stones of un- pleasantness at those who would dare go to the bat for issues affecting ten percent of America’s population,” she continued.

Over the course of their career, Dunnigan would be forced to cover stories from the service section during Eisenhower’s presidency and came out of pocket to pay for her own accommodations during President Harry S. Truman’s entire Western campaign. Payne almost had her credentials revoked due to her complex questions and succumbed to low pay in comparison to her male counterparts while working as a one person bureau in D.C.

Despite these obstacles, the pair fiercely overcame each setback with grace leading to a series of awards presented posthumously. In 2022, the White House Correspondents’ Association created the Dunnigan-Payne Lifetime Achievement Award in their memory.

“For the Chicago Defender, Ms. Payne was a frontline journalist of the highest order and a lion for her people. Even today, few journalists can match her skills, fearlessness, sagacity and curiosity combined with an unquenchable thirst for excellence. Those attributes led her to serve with distinction as our White House correspondent and travel the world and Chicago covering issues that concerned her people, Black people,” Tacuma Roeback, current managing editor for the Chicago Defender expressed. “She is and will always be “The First Lady of the Black Press,” but she deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Ida B. Wells, Helen Thomas and Barbara Walters.”

Payne was a classically trained journalist who studied at the prestigious Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University while Dunnigan earned her degree from Kentucky State University.

“In an endeavor where doggedness and fearlessness are virtues, Alice Dunnigan embodied both more than most journalists, regardless of race, gender or orientation. As someone who had to bear the twin burdens of racism and sexism, what she achieved throughout her career is nothing short of remarkable,” shared Roeback. “When individuals are singled out for being “one of one,” they have the rare ability and self-belief to reach the upper echelons of their professions. Considering the racial and gender bias they endured, Ethel Payne and Alice Dunnigan are truly in that “one of one” category.”

The last lectern was introduced in 2007 under President George W. Bush and remained for a total of 16 years before being replaced. A team comprised of those in the Army, Navy and civilians assigned to the White House Communications Agency designed the new one over the course of 2023. It stands as a silent reminder of Payne’s parting words.

“I stick to my firm, unshakeable belief that the Black press is an advocacy press, and that I, as a part of that press, can’t afford the luxury of being unbiased,” Payne said. “When it comes to issues that really affect my people, and I plead guilty, because I think that I am an instrument of change.”