By Quintessa Williams

Word in Black

When this year’s National Assessment of Educational Progress showed Black kids’ reading proficiency was the lowest of any racial group, some critics blamed education reforms like the Science of Reading, a phonics-heavy instructional model, for the poor scores. Others argued that teachers should ditch cutting-edge techniques and get back to basics.

However, Diana Greene, CEO of the Children’s Literacy Initiative, says the debate over reading reforms misses the point entirely. If Black kids are coming to school hungry, exhausted, stressed out at home — or not coming to school at all — teaching them to read will be an uphill battle at best.

Sign up for our Daily eBlast to get coverage on Black communities from the media company who has been doing it right for over 132 years.

“When students are dealing with poverty, trauma and chronic absenteeism, they’re not in a position to benefit from reforms,” Greene says. “The Science of Reading works but it’s not enough on its own. We keep looking for a silver bullet when what’s needed is a multi-pronged approach. We have to stop pretending this is just about instruction.”

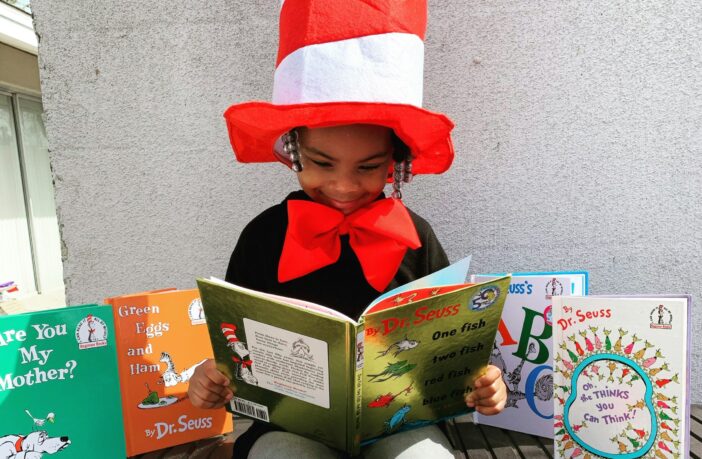

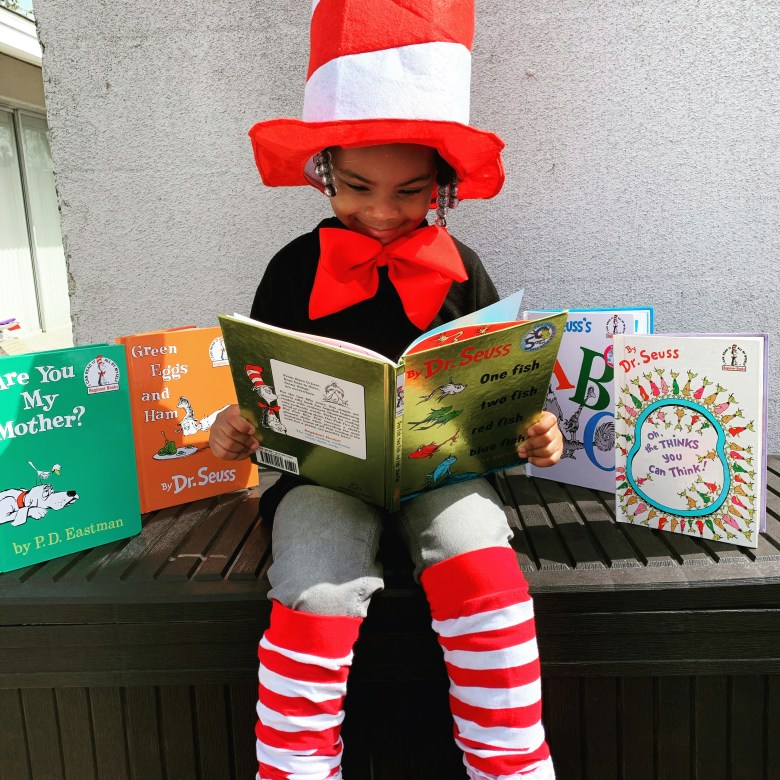

Since family members are a child’s first teachers, families have to be empowered to build the joy of reading and learning at home, not just rely on schools, advocates say. (Credit: Unsplash/ Catherine Hammond)

Since family members are a child’s first teachers, families have to be empowered to build the joy of reading and learning at home, not just rely on schools, advocates say. (Credit: Unsplash/ Catherine Hammond)

Socioeconomic barriers keep Black students behind

To Greene, the real issue is what Black students experience outside the classroom. Barriers to learning are next to impossible to overcome, even with additional support. Tutors, innovative teaching models and tech aren’t effective if a child doesn’t know where she’ll sleep at night or where their next meal is coming from.

]]>

Recent data confirms this reality: The National Center for Education Statistics found in 2023 that nearly 4 in 10 Black students attended high-poverty schools, where access to resources, experienced teachers and intervention programs is limited.

Feed the Children, a nonprofit that addresses child hunger, adds that food insecurity “translates (s) to lower math and reading scores, can also lead to more absences and tardiness.” Hungry children, it states, “are less likely to graduate high school. There are also school-related emotional and social setbacks when a child doesn’t have enough to eat.”

Then there’s the challenge of chronic absenteeism, defined as a student missing 10 percent or more of the school year. Attendance Works, a nonprofit focused on solving truancy, found that, during the 2022-2023 academic year, nearly 60 percent of all majority-minority, low-income schools struggled with extreme, chronic absences.

“You can’t teach a child to read if they’re not in the classroom,” Greene says. “And when they’re navigating unstable housing, community violence, or family trauma, showing up consistently becomes a major barrier.”

]]>

Greene also warned that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is being overlooked.

“We’re still reeling from 2020,” Greene adds. “That disruption created literacy gaps we haven’t recovered from — especially for Black students who were already underserved.”

What’s missing?

Greene argues that today’s reading reforms don’t focus on early intervention and family literacy — meeting kids where they are, not where we want them to be. Through her work with CLI, she prioritizes coaching early childhood educators and helping families see themselves as essential literacy partners.

]]>

“Families are their child’s first teachers,” Greene says. “We have to empower them to build that literacy joy at home, not just rely on schools.”

Data shows that this early foundation matters. Research from the National Institute for Early Education Research shows that Black children are less likely than their White peers to attend high-quality early childhood programs — a gap that leads to early literacy deficits before kindergarten even starts.

Greene points to promising tools like Stanford’s ROAR (Rapid Online Assessment of Reading). ROAR is a digital screening tool designed to catch struggling readers early, helping prevent some students from falling through the cracks.

Though tools like ROAR have potential, “they’re not magic,” Greene says. “They must align with state standards, and schools need resources to act on what those screenings uncover.”

]]>

Locate the root causes, not a “silver bullet”

For Greene, the takeaway is clear: there’s no single fix for Black students’ literacy struggles.

Instead, she calls for a holistic, equity-driven approach that prioritizes the whole child. This includes investments in early childhood literacy programs in marginalized communities, initiatives that emphasize the joy of reading, and training teachers to connect with students’ lived experiences.

“Reading shouldn’t be dreadful,” Greene says. “It should be learning, work and joy. But we can’t get there unless we support the whole child and the family. Until we address the root causes — poverty, absenteeism, lack of access — Black students will continue to be left behind.”

This story was originally published by Word in Black. The original story can be found at this link: https://wordinblack.com/2025/03/reading-the-room-why-black-kids-need-more-than-the-norm/.

Read what we will cover next!

132 years ago we were covering Post-Reconstruction when a former enslaved veteran started the AFRO with $200 from his land-owning wife. In 2022 we endorsed Maryland’s first Black Governor, Wes Moore. And now we celebrate the first Black Senator from Maryland, Angela Alsobrooks!