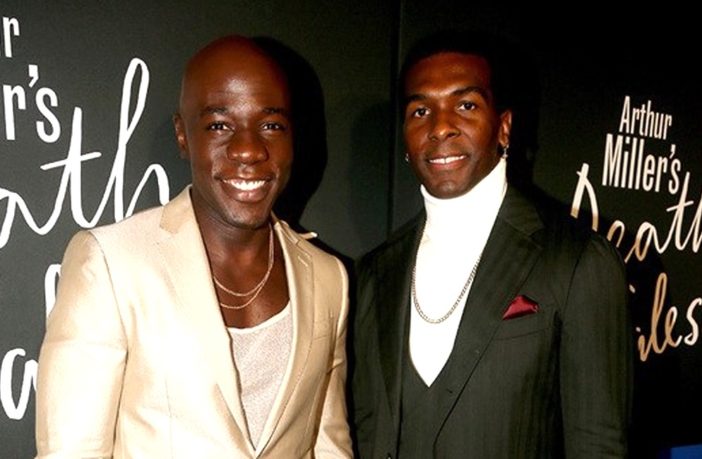

Khris Davis and McKinley Belcher III are making history in Death of a Salesman. As brothers Biff and Happy Loman, respectively, they are part of the first Black cast on Broadway to take on Arthur Miller’s tragic drama that rips apart family structure, dynamics and expectations. It’s an American story that defies color, and one that got the two actors exploring male vulnerability and the demands on Black men to stand strong under all costs.

In true brotherly fashion, the actors sat down with one another to discuss how the suppression of vulnerability can have a devastating toll on Black men, plus their strong connections to their characters, their real-life siblings and each other.

On bringing Black male vulnerability to the stage

McKinley Belcher III: When you talk about what it’s like to be Black in America and the truth of that experience, it’s important to look at the public self and the private self. This play is about the private sector. We’re stepping behind the closed doors, in their home to the inner workings of that family, for better or worse. And I think with each of the characters in this play, we get to see a peek behind the curtain: what they’re feeling, how they’re dealing with it, how they’re struggling and failing in that struggle.

Khris Davis: I think about humanizing our experience to the degree where you see how vulnerable we can be with each other. There’s this thing that you have got to be a strong Black man or the strong Black woman, and we have to hold so much of it inside. The vulnerability only comes by way of yelling or fighting. But I think that this play gives us the opportunity to express more of a nuanced experience as human beings. The brother who just passed away, Stephen “tWitch” Boss, didn’t have anywhere to go, or he thought he didn’t. There is this idea that as a man, especially a Black man, I have to be strong. I have to uphold it. I have to be able to walk with it. I have to carry a lot.

Belcher: It’s an example of that public versus private. In tWitch’s public persona, people saw a really happy person who was vibrant and living fully. But privately, he must have been dealing with something that was heavy and difficult to wrestle.

Davis: And nowhere to be vulnerable. We’re both Black men and I think we both can attest growing up, to how difficult it was to articulate a fear or a doubt or anything of that nature. To be that vulnerable was putting yourself in danger.

Belcher: I feel the essence of true strength or courage is not pretending that you don’t have fear. It’s being able to, as a man, engage with your fear, live with it and find how you overcome it.

On parts they were destined to play

Davis: I connected to Biff on a deeply personal and spiritual level. When I first read the piece, it felt like a story that I had to tell, and it was important for me to do a bit of my own personal healing through it. I felt so close to his experience and his deep desire to be himself. I had a lot of expectations and parameters put on me by my parents and society. I was considered weird and a bit of an outcast, even though I played sports my whole life, I never rode the bench ever. But still, I was a weirdo. Screaming out loud, “This is who I am,” I admire that about Biff. I think it’s such a brave thing to do, especially with a parent. Why did you want to play Happy?

Belcher: It was very much a surprise because I never really thought about playing Happy. And then I was like, “Well, what do I have to say and what is it going to teach me?” In the world, people see me as quite serious, centered and thoughtful. But a lot of people who know me see me as quite funny. I haven’t had a lot of chances to play with levity and have a little fun. So I was excited by the opportunity to play someone who is dealing with some real stuff and feeling deeply connected to his family and reaching out for validation, appreciation and love. But on the other side, he’s chasing joy at all costs. I thought maybe it would force me to investigate myself as an actor in a different way. It’s a powerful thing when you get a chance to show a different side of yourself.

On playing brothers on stage

Davis: I think it’s easy, not because the work is easy. But I think when you build a relationship the way we have, over the course of time, you know, starting with The Royale .

Belcher: Full disclosure. We did a play together six years ago called The Royale at Lincoln Center, where you played a heavyweight fighter and I played your protege. It was our first big thing in New York. That’s a very special thing to experience with somebody who’s close to the same age as you. I feel like we’ve artistically grown up together.

Davis: That’s why playing brothers is easy. Stepping into this piece together, I think that growth is shown on stage. People are always asking if we knew each other before, or if we just started the connection process, because of the chemistry we have on stage. I think that we have it without even trying because of the history that we have and our respect for one another.

Belcher: It’s a blessing. It means that I trust you. We came into this imaginary world with an investment that is different than meeting somebody fresh. One of the things I appreciate most about my experience of doing this show is that we get to live in that.

On their real-life sibling relationships

Davis: I have a lot of siblings and I’m the oldest, so some of them I had the opportunity to experience throughout their lives and others I didn’t. My relationship with most of my siblings is really good. I actually call myself a third parent. I didn’t really have a normal childhood. I spent a lot of time changing diapers, feeding people, giving them baths, dressed and to and from school. I actually took a lot of pride in being an older brother. It meant a lot to me to have them feel safe and secure around me. And to this day, I am someone they continue to call. I create a safe space for them to be vulnerable. It’s a beautiful thing, I believe.

Belcher: I have an older sister, but I function as the oldest. I feel like Mr. Fix It; when people have problems, I’m the person they come to. When things are going well, I rarely hear from them. I’m one of four, but I grew up the middle of three. There’s this thing about being a middle child. My experience is that you become very self-sufficient and independent. So I feel like my parents and siblings just assume I’m fine all the time and don’t need anything. But sometimes you need support and validation and you need someone to just check on you. I think the assumption is that I don’t need those things because I can take care of myself, that’s my relationship with them.

On future dream roles

Belcher: I have two. One is something that came up earlier that I couldn’t say yes to at that time, and I’m praying that it comes back around. So I would love to play Hamlet. I’ve done a good amount of classical work, specifically Shakespeare, and I feel like I’m ready to play Hamlet. And then, talking about things that are not written necessarily for a Black actor. I love Tennessee Williams because I’m a Southern dude, so Lawrence Shannon in The Night of the Iguana. I’m excited by it because it’s a man dealing with his faith, and that’s a complicated thing for me. I would love that to intersect with my work because I’m still figuring some of that out. Williams’ words are beautiful and I hear them in a way that’s familiar which makes me excited about tackling it.

Davis: There’s a play, I saw a friend do it years ago. It’s called Diary of a Mad Man. It’s about this accountant who lives in an attic and he keeps having these accounts of his daughter. She’s showing up in her tutu, doing ballerina moves, and she’s the only one talking to him. But she’s a figment of his imagination and he doesn’t know how many days have passed, but days go by and people are knocking on the door trying to get him to come out. He’s losing his mind in that attic by himself. It’s supposed to be played by someone in their 50s or 60s, but our understanding of mental health is so more in-depth that the possibility of a young individual losing their mind is highly likely. When I saw my boy do it, I was like, “Yo, this piece is what?” It’s bananas.

Death of a Salesman is on limited engagement through January 15, 2023, at the Hudson Theatre in New York City.