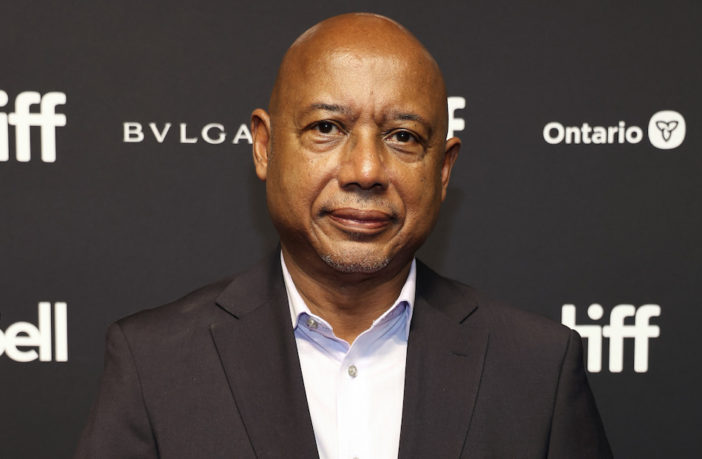

The new documentary Silver Dollar Road from I Am Not Your Negro director Raoul Peck introduces us to the Reels family, a tight-knit unit fighting to retain their rightfully owned land in the heart of Carteret County, North Carolina.

Lying along Adams Creek, patriarch Elijah Reels officially took ownership of the 65 acres known as Silver Dollar Road in 1911, and generations have lived and thrived off the land. But he left no will when he died, and the land went into “heirs property.” A distant family member sold off his share without consulting with those who had resided there all their lives.

Two family members, brothers Melvin and Licurtis, had houses on the property and refused to vacate the land. “They were born on that land. Their grandmother was born there and their great-grandmother. It became a huge fight for decades,” Peck shares.

Melvin and Licurtis, both over 50 at the time, were sent to prison, where they remained for nearly a decade, one of the longest cases of incarceration for civil contempt.

“They stayed in jail for almost eight years for doing nothing and without having committed a crime,” Peck exclaims. “That’s a profound injustice, but they continue to fight for their land.”

Below, Peck reveals more about this riveting true-life tale.

EBONY: Watching this movie, I felt so many emotions like anger and sadness, but also hope. Was your goal to elicit these emotions in me and others watching it?

Raoul Peck: Most of the time, you can’t control how your audience will react. I knew I had a genuine, strong story of injustice and people resisting and not folding to the powers. I knew it would trigger anger, of course, but also show if this family could resist for so long for many decades, there is hope and strength. This is a very common story for Black families. There is always a land story and the stuff that you lose, that you’ve lost. And that is dramatic. I’ve talked to many people about how there was such a story in their family, but they didn’t want to talk about it because it was a loss. Where do you go back to? Where is your home? Where do you come from? Because whether you know it or not, it’s part of your identity.

Knowing that Melvin and Licurtis had one of the longest jail sentences for civil contempt in the United States shocked me.

Sending two elderly Black men to jail and forgetting about them in a jail cell when there is no reason for them to be there is enraging. When you’re condemned for something, you know for how long. But these brothers didn’t know how long they would be there. Imagine that additional trauma and that kind of injustice. When Curtis says, “I try every day not to hate,” that hits you very deep.

Your opening shots are just so beautiful; you really feel the land. Was that the imagery you wanted to capture?

As a filmmaker, you are like a surgeon on the operating table; you don’t have time for feelings, you have to make sure that the patient’s going to survive. So I’m more in that state of mind. It’s only toward the end, when I can sit down and watch the film that the feelings come up, and I’m happy that I have caught something and it’s working. Until you finish, you’re making sure that you get the story right. I didn’t want to make another report about this case. I have all the statistics and numbers, but I needed to put that family, each one of them, on the front line. They are the ones telling their stories. How often do you have a rural Black family on the big screen where you are in their living rooms, forests and waters as they tell their stories? It’s a life that people forget exists. These people were happy and had everything they needed. They didn’t need to work for anybody else. They were farming and hunting and fishing; they had their own boats. So to have the rest of the world crash on them like this, for speculation, money and greed, is a painful realization.

I can’t stop thinking about the family member who sold his portion of the land without the family’s input. Do we know what happened to that person? Did he feel any guilt?

That’s an interesting reaction. I left that out on purpose. Because it’s not about that person. But that guy sold it to a company, and that company sold it to a white man who had a lot of money and never set foot on the property. He bought it on paper. So it’s about the structure that allowed something like this to happen. It’s the justice system, the lawyers and the judges. All of them allowed that to happen. I want people to focus their anger or questions on the system because that’s the problem. It’s a system that has existed since the beginning of this country, which was bought on stolen land. The original inhabitants of South and North America never said this land belonged to them. They were just custodians of the land. It’s a European concept that you could buy, own and exchange land. Through this real family story, you can see all the rest of the structure and the history behind it.

As you say at the film’s beginning, land ownership is power. How do you hope this film helps the Reels family?

I’m making sure that the Reels family has help. You can follow their story at SilverDollarRoad.com. I’m pretty sure the family will manage. The worst part is behind them. We now know that the world is watching, so it’s a different ballgame. I do hope that things will change tremendously.

Watch Silver Dollar Road on Prime Video beginning October 20.