Even before Dusty Baker led the Astros to a World Series title this past season, the baseball lifer was already among the most revered and admired in sports.

The dignity and honor with which Baker carries himself have made him a hero to many. But interestingly, that’s not the reflection he necessarily sees.

“No. 1, I don’t feel like a hero,” Baker addressed a questioner during Wednesday night’s NAACP’s “An Evening with Dusty Baker.” “I’m serious about that. Maybe I am, but I’m just Dusty. I’m blessed. I was chosen to be in this situation. I didn’t choose this.”

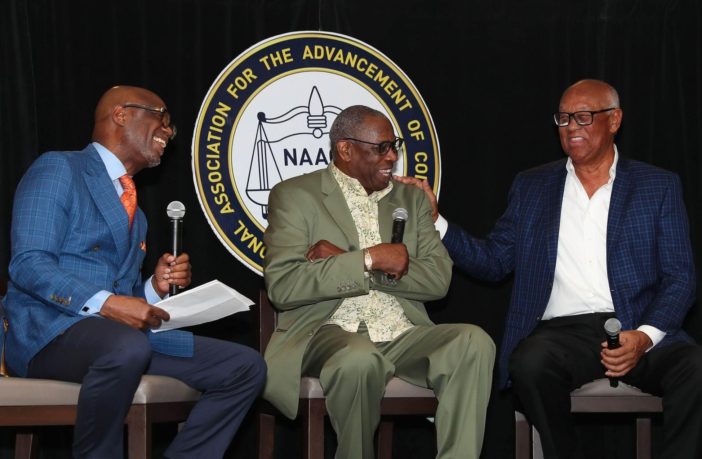

A baseball legend who cemented his future Baseball Hall of Fame nod with his first World Series championship as a manager, the 73-year-old Baker wowed the more than 200 attendees throughout the night at the Minute Maid Park Diamond Club. Baker was joined on stage by former baseball player and now Astros assistant to the general manager Enos Cabell and NAACP Houston Branch president, Bishop James Dixon.

With Dixon, who last year became the chairman of the Harris County Sports Authority, acting as the moderator, the three talked about everything from Baker’s childhood and his family’s involvement with the NAACP. However, the night wouldn’t have been complete without stories of Baker’s and Cabell’s early playing years in the late 1960s and 1970s, along with plenty of laughter.

The trio didn’t fail to entertain while also enlightening the crowd that included dignitaries such as Mayor Sylvester Turner, Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee and Harris County Precinct One Commissioner Rodney Ellis. Baker, who was an NAACP Legends awardee, met with 100 kids from the area and personally took them on a tour of Minute Maid Park.

“It’s about those children in there. This is all for them,” Baker said. “Just like I was reading Proverbs the other day, it said a good man will leave an inheritance for his children’s children. I was like, `Dang, I have enough for my children. I’ve got to keep on working. I’ve got to get something for my children’s children, because that’s what rich white people do.”

Baker spent the evening dropping gems on the audience, while also giving them plenty of his usual humble and down-to-earth self.

“I try not to be judgmental and try not to choose your friends based on their economic prowess in life,” he said. “I’ve got people in my family who’ve been to jail. I’ve got people in my family who are missionaries. I’ve got people in my family who have money and don’t have no money. And they are all my people, and they are all my family. Sometimes I have to jack some of them some time, but they are still all my family.

“Most of my longtime homeboys, I went to elementary school with them. My homeboys are my homeboys. And I will give you a chance until you mess it up.”

Baker talked about his early years, growing up in the Los Angeles area in the 1950s and 1960s, being a product of a two-parent home where his mother was an educator and his dad was the disciplinarian in a home where church and involvement in the NAACP were a way of life. What was most interesting is that Baker’s dad was also his Little League coach and cut him when he was 8, 9 and 10 years old.

“When he cut me when I was 10, he nicknamed me hard-headed because he said, `You don’t learn too quick,’” Baker recalled. “He said I had a bad attitude, and I’m big now on attitude.

“He said I had a bad attitude and if I could take that bad attitude and put it in the proper direction that I could be something one day. That’s what got me on the right trail.”

It was because of the discipline instilled in Baker that he was likely able to navigate the tricky and dangerous waters of playing baseball in the South for the Atlanta Braves organization after being drafted in 1968. Baker, like all Black players at that time, had to adjust to the oppressive laws in the South that restricted where they could stay, eat and socialize.

And to think, Baker had defied his father and went behind his back to sign a contract with the Braves only to be subjected to such treatment. Baker and his father didn’t talk for three years as a result.

“I sneaked away and signed with the Braves,” Baker said. “And I prayed to the Lord, `’Lord whatever you do, don’t let me get drafted by the Atlanta Braves because I don’t want to go to the South.’ This was 1968 and they were having riots and throwing brothas in the swamps. It was tough.

“The next morning I found out I was drafted by the Atlanta Braves. I said, `Lord, you didn’t hear me.’”

It was in Atlanta that baseball legend Hank Aaron took Baker under his wing, introduced him to the local NAACP chapter and he got to meet Civil Rights Leaders like Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young and a young Jesse Jackson.

“Here I was, praying that I didn’t go to the South, and that was the best thing that happened to me,” Baker said.

Cabell and Baker shared some of their war stories from those early years. They talked about how the Black and Hispanic players had to move in packs together and how it was always the responsibility of the Black players from the host team to take the Black visiting players out to dinner after games.

“If you didn’t, you didn’t eat, because we couldn’t go places to eat,” Cabell said. “When I first came to Houston, we couldn’t go to Westheimer in 1974.”

“And when we went to Atlanta, you couldn’t go to Buckhead,” Baker said of the now well-known area. “You could go to Buckhead during the daytime, but not at night.”

After his playing days, Baker went on to an impressive managing career. He has become one of the most decorated and respected managers in the game with 2,093 career wins and numerous playoff appearances and wins during a managerial career that began in 1993 with the San Francisco Giants. But interestingly, Baker didn’t always want to be in baseball after his playing career was over.

He actually began a post-playing career as a stockbroker until there was a push by Major League Baseball to groom more African American managers. When initially approached, Baker wanted no part of coaching until a soul-searching getaway trip gave him the answer he was seeking.

While waiting in line to check into his hotel in Lake Arrowhead, Calif., Baker was tapped on the shoulder and when he turned around it was the San Francisco Giants owner and he told Baker that he needed to come to join the organization as a coach.

“I didn’t see the guy the rest of the weekend and if I had gotten there two minutes later, I would have missed him,” Baker said. “So I called my dad and said, `Pops what do you think? Is that a sign?’

“He said, `Boy, you went up there to pray for direction.’ God sent the coach and I don’t want to see it. That ain’t the sign that I wanted to see.”

So Baker packed up and moved up to Northern California, giving it five years to see how things worked out.

“It was five years and one day and I was named the manager of the Giants,” Baker said.