The drums roll. The beat starts. Frankie Beverly’s voice belts a familiar elongated “whoa.” Then everything stops for a split second until the electric guitar comes in and blares out of the speakers. In the right crowd, those opening seconds of “Before I Let Go” create a proverbial tsunami where waves of friends, family, and even strangers vibe together. Like many of Beverly’s creations with his band Maze, that song became the soundtrack for family functions for multiple generations.

On Tuesday, the man responsible for those sounds died Tuesday at age 77. Beverly’s career stretched across decades because he built a brand in R&B and funk that was unique to him and his band. It was all about the personal touch with the Black community. Beverly and Maze had toured incessantly since their early days, first opening for Marvin Gaye in 1971.

Even after 40 years, Maze and Frankie Beverly play onRead now

Beverly, whose full name is Howard Stanley Beverly, loved the road so much that he didn’t retire from touring until this year’s I Wanna Thank You Farewell Tour. The group released its last studio album in 1993. How many musicians can hit the road and play in front of packed houses 30 years after their most recent album release? As a Maze cover band drummer once said, “Maze is like the urban version of the Grateful Dead.” Like the late Jerry Garcia’s band, Maze’s music symbolized a lifestyle. Their tunes and the man behind them became more than music.

Beverly never really crossed over to mainstream white listeners. Despite the fact they showed at his concerts, hearing “Happy Feelin’s” or “Joy and Pain” on a radio station catering to white listeners was as rare. Former Capitol Records vice president Larkin Arnold attributes that to racism. “I had a lot of fights with my pop promotion department because they would never expose that album to white FM,” Arnold said. “That first time I saw Maze, the whole audience was white. I know if white people were exposed to Maze, they’d like it, but the belief at the time was, ‘Well, white people really don’t want to listen to Black music.’ ” Arnold tried in vain to convince his colleagues that Beverly’s band was more significant than just “Black” music.

Nine gold albums is nothing to sneeze at, but it’s nowhere near the heights Beverly deserved. Or, probably more importantly, that one might think he achieved, given the ubiquity of his music. Maybe the music never received mainstream attention because the group’s record labels, Capitol Records and Warner Bros., didn’t push it properly. Or perhaps it’s because Beverly stuck to his vision and made his music without compromise for radio play or awards. “I just refuse to compromise the music and, therefore, I’m going to have a problem with radio,” Beverly told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1985. “You start changing your music and it’ll wind up hurting you.”

Like the Grateful Dead, the Philadelphia native stuck to what worked with the people who paid to watch him and his band perform. Even as the genre gave way to Michael Jackson, Prince, Whitney Houston, and later Jodeci and Mary J. Blige, Beverly stuck to his principles. In an ever-changing world, his music was a constant.

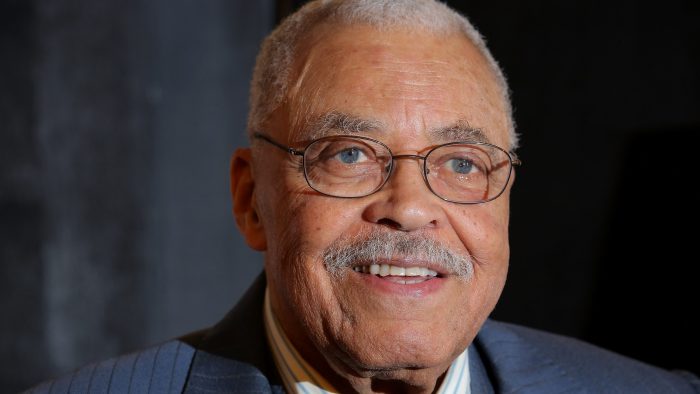

Singer Frankie Beverly of Frankie Beverly & Maze with the Phoenix Award onstage during the Frankie Beverly and Maze Farewell Tour at State Farm Arena on March 22 in Atlanta.

Singer Frankie Beverly of Frankie Beverly & Maze with the Phoenix Award onstage during the Frankie Beverly and Maze Farewell Tour at State Farm Arena on March 22 in Atlanta.

Paras Griffin/Getty Images

“The love the people give us is most amazing,” Beverly said, describing his group’s continued success. “I don’t care about no Grammys. It’s about the reward, not the award.” While some fans gasp when their favorite artists don’t get the props they believe they richly deserve from award shows or the industry, the lack of trophies on his mantel never bothered Beverly. He made his music to unite people and inspire them with love, kindness, and joy. “I look out in the audience and see multigenerations getting along, and it enthuses me,” Beverly said. He reveled in performing in front of an audience, regardless of how many people showed up. His dedication to a crisp performance started at age 16. Beverly kept to that core belief for his entire career. “It’s just a special thing. It’s probably the most powerful form of art, is the music and the live thing,” Beverly told NPR in 2005. “You know, you say ‘Hey,’ they say ‘Hey.’ You say ‘Ho,’ — and it just comes right back at you. It’s — just nothing like it, man.”

James Earl Jones: The great Black heroRead now

James Earl Jones: The great Black heroRead now

For Beverly, the guy discovered by Gaye and who grew up idolizing Sam Cooke, his music was always about the people. When Questlove Supreme podcast host Questlove of The Roots interviewed him in February, Beverly deferred to the fans who gave his soulful songs a deeper meaning. He deflected praise from Questlove and his co-hosts. He always considered how the music affected the fans rather than what the fans could do for him. That’s how “Before I Let Go,” a song released in 1981 about heartache, was transformed into an uptempo anthem still played at cookouts, block parties, weddings, and anywhere Black people gather to celebrate.

When Beyoncé covered “Before I Let Go” in 2019 for her live album Homecoming, Beverly told Billboard how excited he was that someone of her stature made her version. “She’s done so much. This is one of the high points of my life.”

That’s typical of a man who always thought about us with every lyric he wrote and every move on stage. During his 60-year career, he prioritized music and fans. That’s why Frankie Beverly and Maze endured for six decades and will continue for six more.

We’ll never let go.

Marcus Shorter is a communications professional and writer. When he’s not scribbling thoughts for Consequence, Cageside Seats or Bloody Disgusting, he’s getting extra nerdy about rap lyrics, politics, poetry and comic books.