By Ron Taylor, Special to the AFRO

and Alexis Taylor, AFRO News Editor

When Denise Dorsey entered the world of journalism production, ideas and images were transferred from writers’ typewriters to a printed page in a belabored process that dated back centuries. Now, thoughts surface on a palm-sized device and production teams can send entire publications to a printer with the click of a button.

Though the tsunami of tech innovation left no part of the globe untouched, Dorsey rode the wave into a media production career that has stretched five decades. She is now among the millions of baby boomers who met the evolution of technology and didn’t back down– in fact– she excelled.

When Dorsey started at the AFRO, the production process was more than a bit laborious. The dedication and persistence it took to produce even one edition of the paper was nothing short of an act of love for Black press to keep Black Americans informed.

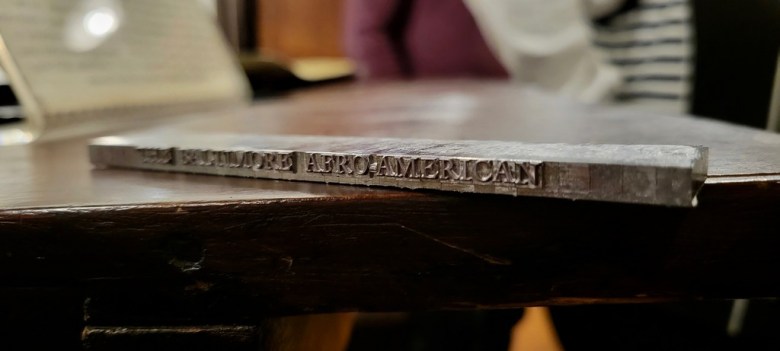

The AFRO, like all printed publications of the day, used a system of hot type in the 1900s and cold type in the 20th century. Baltimoreans can take a look at the hot type process by visiting the Baltimore Museum of Industry, where hot type demonstrations take place as part of an exhibit that includes items from the AFRO American Newspapers.

In the late 1800s the most widely used production process included pressing molten metal into forms that created letters of the alphabet. The letters were then put together to compose words that would eventually be inked and printed onto paper. This was considered “hot type.”

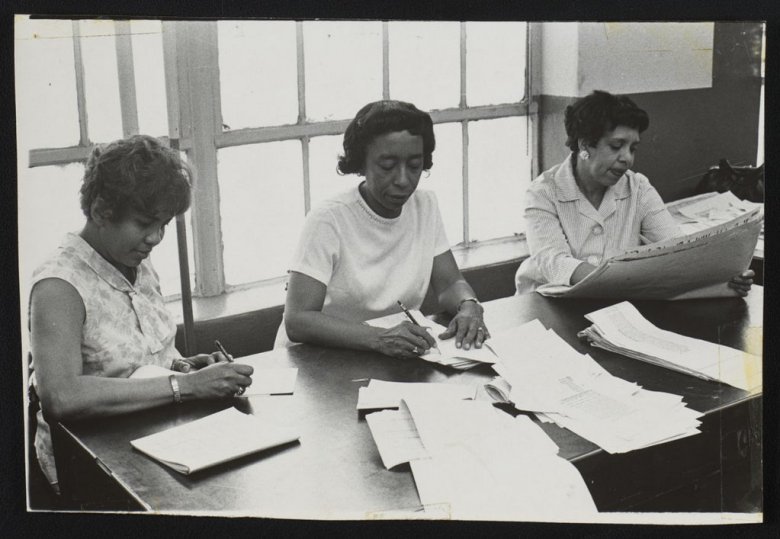

In 1976 the AFRO didn’t have digital spell check– they had (from left to right) Mesdames Bertha Jordan, Beatrice Wilson, proof room forelady, and Eva Barnes. Together they served the AFRO for a total of 60 years and made sure each page was free of errors. (AFRO File Photo)

In 1976 the AFRO didn’t have digital spell check– they had (from left to right) Mesdames Bertha Jordan, Beatrice Wilson, proof room forelady, and Eva Barnes. Together they served the AFRO for a total of 60 years and made sure each page was free of errors. (AFRO File Photo)

According to the University of Dayton in Ohio, cold type “refers to any method of type composition other than hot type. Type is cold because hot lead is not used.”

Today’s production process is completely digital, but Dorsey clearly recalls the processes of days gone by.

“Cold type was when they were actually typing things into a machine. It would come out in long strips of paper that they would send to the production floor,” remembers Dorsey. “They would actually paste it up on the templates. We had templates like the template that we use now in the computer.”

It took a mighty team to make sure each article got onto the page correctly- and then there was the challenge of photographs.

“We had a dark room then, so, of course, there was no digital . The photographers had negatives and they had to be processed.”

Once all of the pages for all of the unique editions of the AFRO were put together, a courier then had to come to the building, physically pick up the pages and take them to a printer.

Though she now is responsible for creating the cover and layout of the paper with production assistant Mishana Matthews, Dorsey started off in a smaller, but yet, important role.

“When I first came in 1976, I was only working on the advertising side. My job was marking up ads to send down to the typesetter.”

Dorsey eventually became more involved with creating the pages that kept Black readers informed up and down the East Coast and beyond. Before long, she began helping the production team fill templates by pasting the articles and photographers together.

The AFRO American Newspapers is part of a permanent exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Industry. Visitors can see how the newspaper was put together from start to finish with the process of “hot type,” a method that involved molding each letter printed on the page from molten metal. (Photo by Alexis Taylor)

The AFRO American Newspapers is part of a permanent exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Industry. Visitors can see how the newspaper was put together from start to finish with the process of “hot type,” a method that involved molding each letter printed on the page from molten metal. (Photo by Alexis Taylor)

Today, Dorsey is no longer pasting together strips of paper to create each edition of the AFRO. In the 1990s the company began using computers in the production process. With the help of two dedicated AFRO women, and others in the production department, she learned how to use digital platforms to create each page.

“They were instrumental in teaching me InDesign when we began using that instead of Quark. Both were great graphic designers and I learned a lot from them,” said Dorsey. “It would be remiss of me to not acknowledge all those who helped me.”

Aside from in-house support, AFRO administrators sent their production team to the Maryland Institute College of Art to learn the finer points of producing a newspaper with new technology. They also had training from the Maryland, Delaware and D.C. Press Association.

Dorsey said mastering technology on the production side of the newspaper business was key in surviving the tech evolution. She said mentors helped her hone her computer skills, which have paid off to this day.

“It kept me there while other positions were starting to be eliminated,” said Dorsey. “One of the women who was there in the early 2000s helped set up the transition of us sending the pages electronically and no longer needing a courier.”

When asked how she views the ever evolving nature of technology in the newspaper industry, Dorsey expressed mixed feelings.

“It’s not a bad thing, it just means that’s the future. When computers came in there were people who were upset. I wouldn’t want to go back to how we were doing the paper, but a lot of people lost their jobs,” she said.

Aside from InDesign, other graphic design and production applications Dorsey and Matthews use today are Photoshop and on occasion, Acrobat.

“I find it very interesting to see everything that is available and what is coming in the future,” said Dorsey. If the past is any indicator– she’ll be mastering what’s on the digital horizon too.

Dorsey says she will retire soon, but hopefully the AFRO team can talk her out of it.

Help us Continue to tell OUR Story and join the AFRO family as a member –subscribers are now members! Join here!