SPRINGFIELD, Ohio — Ever since a spate of rumors and lies placed this city on edge, fear has coursed through the Haitian community — fear of the blanc avec babs.

That’s Creole for “white men with beards.“

“They don’t want to live in fear,” Marjorie Koveleski said inside Friendly Bakery and Groceries, an ironic name considering a well-documented lack of friendliness some local residents have displayed toward Haitians the past couple of years. “They are so afraid of the big beards.”

The “big beards” are the white working-class men who don’t like the fact that thousands of Haitians relocated to Springfield in recent years and who have harassed Haitians just because of who they are. In public meetings, some residents have accused Haitians of siphoning off resources from longtime locals and depleting scarce governmental resources.

The bad vibes increased when baseless rumors emerged accusing the Haitians of abducting and eating their neighbors’ pets. Those rumors were shared online by Republican vice presidential nominee J.D. Vance, an Ohio senator, and repeated by Donald J. Trump, the GOP presidential nominee, in his nationally televised debate last month with Democratic nominee Kamala Harris.

The white men in Springfield yell at the Haitians, as the migrants come back from work, school or running errands. They tell them to go home, they’re not wanted, and scream racist insults, people in Springfield interviewed by Andscape say. The Haitians don’t understand, either because of a language barrier or simple confusion.

We’re just here to work and raise our families in peace, they wonder. Why do they hate us?

In the past month, since Vance’s posts and Trump’s debunked pet-eating comments, white hate groups have made their presence known in town with marches or passing out recruitment flyers, causing fear among Haitians, many who have said they’ve changed their daily routines as a result.

The grocery is in a shopping center near South Limestone Street, a main north-south thoroughfare with restaurants, shops, banks and more that’s normally bustling with people.

Instead, on a recent Friday afternoon, the street seemed unusually quiet to Bernald Rock, an American of Haitian descent.

“The south side over here, they’re usually a bunch of people just walking around, lively,” Rock, a local property owner who rents to a large number of Haitian tenants, said. “This morning, I came out and there was no one. Like the laundromat across the street. I’ve never seen it empty before.”

That’s what a “climate of fear,” as Rock called it, can do to people.

Residents display Haitian and American flags in a Springfield community after presidential candidate Donald Trump and running mate, Ohio Sen. J.D. Vance, made inaccurate claims about Haitian residents eating pets.

Maddie McGarvey for Andscape

Over the last several years, the Haitian population in Springfield has grown rapidly, as Haitian migrants have sought refuge from poverty, violence and instability back home. Springfield has a population of 58,662, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, yet it’s impossible to know how many immigrants reside in the city. Springfield, using driver’s licenses and school and health-care data, estimates that 12,000 to 15,000 is the “total immigrant population” in Clark County, where Springfield is the largest city.

Whatever the number, an increase of even 12,000 new residents with a different language and culture would strain city resources while creating an air of distrust that could easily cause anger fueled by innuendo.

It’s difficult to quantify the level of harassment Haitians in Springfield have endured. Supporters say the newcomers are reluctant to make official allegations, such as filing police reports. Attempts to reach the Springfield police officials by email and phone to discuss the alleged harassment of Haitian residents were unsuccessful.

The climate of fear exploded in August after the rumor circulated that Haitians were stealing and eating pets, specifically cats. The falsehoods have been debunked by the city’s mayor, police chief, and Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine. The people who spread the tales now admit they were wrong. One Springfield woman who reported her cat missing found it in her basement; another woman, who spread the pet-eating tales on Facebook and helped sparked the furor, says it was wrong to do so.

But the rumors took on a life of their own when Trump and Vance repeated the comments and said they would keep spreading them.

Trump has lived up to that vow. During his Sept. 23 rally in Indiana, he asked, “Do you think Springfield will ever be the same? The fact is, and I’ll say it now, you have to get them the hell out,” with “them” referring to immigrants. The crowd then broke into a chant of “send them back.”

Krish O’Mara Vignarajah is the president and CEO of Global Refuge, a nonprofit that helps immigrants, or “newcomers,” adjust to America. She called the lies harmful and deeply troubling, noting they “dehumanize people and incite fear for political gain. It’s shameful that we see them persist in 2024 and that we have political leaders who ought to bear a responsibility to lead instead of perpetuating such lies and weaponizing them against Haitians in particular.”

The lies about Springfield have upended Haitians who came to this country to escape the terrible conditions of their homeland, supporters say. Instead of solace, the community finds itself the victim of rage and its own fears about the dangers of the blanc avec babs.

The white men with beards.

Haitian students use their mobile phones to record an exercise on a board during their English class by volunteer teacher Hope Kaufman at the Haitian Community Help and Support Center in Springfield, Ohio, on Sept. 13.

Haitian students use their mobile phones to record an exercise on a board during their English class by volunteer teacher Hope Kaufman at the Haitian Community Help and Support Center in Springfield, Ohio, on Sept. 13.

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

Momma Margery

Friendly Bakery and Groceries smells and feels like home. The cooler contains ginger beer, coconut juice, and Malta, a popular Caribbean drink. Customers can also choose from plantain chips, rice, and yuca on display, and shrimp and cubed goat in the freezer.

People come not only for the food but also to see Koveleski, affectionately known as “Momma Margery.” She works at the store, which serves as a gathering place for Haitians who need encouragement, compliments, and a gentle touch. “Like a mom would do,” she said.

Recently she greeted a grandmother whose daughters and a grandchild had just arrived in Springfield. They smiled and hugged as if they were family. In another instance, she rested her hand on the broad shoulders of a young Haitian man who had come to talk to her, and she immediately praised him for working hard and always looking good.

The young man only speaks Creole, so Momma Margery translated as he hung his head and spoke softly during an interview with Andscape.

The man, who did not want his name used, said he came to Springfield from Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital, a year ago.

His trip wasn’t easy.

He secured a visa to go to Panama before making the trek north. He crossed the dangerous Darien Gap through Panama and Colombia, a 60-mile stretch of dense forest. There, criminals often engage in robbing, raping and even the human trafficking of those heading north, according to UNICEF.

He made his way to Nicaragua before arriving at the U.S. border and securing temporary protected status, which allows immigrants fleeing dangerous conditions in their country to live and work in the United States. Sixteen countries, including Haiti, are eligible for the program, which the president can renew or terminate at his discretion. Trump has vowed that if he’s elected, he’ll deport the Haitians in Springfield, which is located about halfway between Dayton and Columbus, the state capital.

The young man came to this city because he had family in the area and for another reason: “He came because he realized there’s no war here,” Momma Margery said. “There’s security. It was peace.”

Now, peace has turned to tumult.

Haitian immigrants have been moving to Springfield for years, filling a large number of manufacturing and local jobs.

Haitian immigrants have been moving to Springfield for years, filling a large number of manufacturing and local jobs.

Maddie McGarvey for Andscape

A security guard works at Adasa Latin Market in Springfield, Ohio, on Sept. 15. The store owner, Alicia Mercado, said the guard was hired after the area attracted national attention.

A security guard works at Adasa Latin Market in Springfield, Ohio, on Sept. 15. The store owner, Alicia Mercado, said the guard was hired after the area attracted national attention.

Liz Dufour/The Enquirer via USA Today

“What Trump said, it’s really hurtful, when he said that Haitians eat dogs. I’ve never heard of anything like that. It hurts me to the soul, to my heart,” she translated as the young man spoke.

“It’s a tactic for discrimination.”

The young man who came to America to escape violence said he now feels unsafe. He goes to work and to his apartment, which he shares with his family. If he didn’t need to talk to Momma Margery, he would have stayed home.

Momma Margery drew a distinction between the fear you know and the fear you don’t.

“In Haiti, you saw the gangs, you saw the gun,” she said. “So you know which way to turn. But with the big beards, you don’t know. So wherever you go, you’re not comfortable, because you never know where your opponent is going to show up or what they’re going to do, right?”

She said if Haitians have any problems in the community, they often don’t go to the local police but they tell others, which compounds the fear.

“They never know when they will be attacked,” Momma Margery said. “And why big beards?” she added, alluding to the white men accused of harassing Haitians in the area.

Port-au-Prince

Some 1.2 million people call Port-au-Prince home, making it the most populous city in Haiti, a country of nearly 12 million. Haiti is also the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Nearly 6 in 10 residents live below the poverty line, and 4 in 10 don’t have jobs. Criminal gangs control about 80% of the capital, the Associated Press reported, with an overwhelmed police force and inept government powerless to stop the violence.

Nearly 700,000 people are internally displaced across Haiti and more than 110,000 have fled their homes in the last seven months as a result of gang violence.

Viles Dorsainvil fled Haiti with his family four years ago and ended up in Springfield.

Viles Dorsainvil (left) and Rose Thamar Joseph (right) work together at the community center Oct. 1. The community center runs a number of programs, including coat drives for newly arrived Haitians.

Viles Dorsainvil (left) and Rose Thamar Joseph (right) work together at the community center Oct. 1. The community center runs a number of programs, including coat drives for newly arrived Haitians.

Maddie McGarvey for Andscape

Dorsainvil is the director of the local Haitian Community Help & Support Center, which helps residents set up utility accounts and provides advice on finding housing. He patted a box of warm clothes the center planned to distribute because some people might not have the proper outerwear for Ohio’s winter. Springfield’s average high in January is 35, and its low is 18. In Port-au-Prince, the average high is 88 and the low is 73.

Now, it’s just a tad harder to get in the building. Ever since the dehumanizing pet comments led to bomb threats against City Hall, schools, and grocery stores, the community center has kept its doors locked.

Dorsainvil said he received his bachelor’s degree in governance and international relations in Haiti and left the island in 2020. Like many of his countrymen, he didn’t want to leave, but didn’t feel safe. He ended up in Springfield via a family connection, a nephew who was already here.

When he arrived, he said the atmosphere was “calm. There wasn’t that much attention to Haitians.”

But the coronavirus pandemic changed that. After federal lawmakers ended stimulus checks designed to keep the economy afloat in 2021, some of the locals started falsely claiming the government was taking benefits from them to give to Haitians. “They cast the blame on us,” Dorsainvil said.

Then, in 2023, a Haitian immigrant without a valid driver’s license hit a school bus in Springfield, and an 11-year-old boy died. (The driver has been sentenced to up to 13.5 years in prison.) Furious residents started openly criticizing immigrants and advocating to “send them back.” The case also made national news.

“The folks that were angry were seeing things that they wanted or felt that they should be getting that was going to someone else — full grocery carts, rides to jobs, rides to wherever, the vans all over town,” resident Diane Daniels said during an October 2023 city commission meeting, according to the Springfield News-Sun. (Some factories use vans to pick up Haitian workers.)

Others protested, too. At the Aug. 28 commission meeting, one white resident complained that a city task force just makes it easier for “you to be an immigrant.” Another complained rude immigrants need to show common respect and decency. Several speakers at subsequent meetings expressed displeasure on how the city has handled the immigrant issue. But citizens have also preached patience and understanding for their new neighbors.

Then, during the nationally televised presidential election debate Sept. 10 with Vice President Harris that drew more than 67 million viewers, Trump repeated the debunked rumor of pet-eating Haitians, and blame mushroomed into hate.

Since his remarks, the extremist the Proud Boys have gathered in the city, the Ku Klux Klan has distributed anti-Haitian flyers, and the white supremacist Aryan Freedom Network nailed signs to telephone poles. The city even canceled its two-day CultureFest due to threats and safety concerns.

“People fear for their lives, especially since they came from a background where violence is predominant,” Dorsainvil said. “They came here with the expectation that they could work peacefully and raise their families, and they get into the middle of [this]… It’s very sad.

“I feel so disappointed to see myself, after all those kind of studies, coming here to get those allegations against me [and]to be discriminated against,” he said referring to his schooling. “I have been so disturbed, perturbed, and at the same time asking myself why it is like this for Haitians when they could live in the country and raise their families. We [have]never experienced peace, at home and abroad.”

Creations Market shop owner Philomene Philostin shelves merchandise in her store that caters mainly to Haitian residents.

Creations Market shop owner Philomene Philostin shelves merchandise in her store that caters mainly to Haitian residents.

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

Revitalizing a declining city

At one point, Springfield was a vibrant Midwest city awash in jobs. The 1980 Census showed more than 72,000 people called Springfield home. In 1983, Newsweek magazine featured Springfield in its 50th anniversary edition because it saw the city as a microcosm of American life and the American dream.

But then the population started dropping as large manufacturers either cut jobs or left. Springfield’s median household income plunged 27% from $73,895 in 1999, to $53,937 in 2014, the worst drop in the country, according to Pew Research Center.

To try to turn things around, the city passed a resolution in 2014 to encourage immigration to help reverse the population decline, according to the Springfield News-Sun. The city added 7,000 jobs over the last several years, according to the Greater Springfield Partnership, and employers needed workers to fill them.

Locals say that the opportunities in Springfield spread to Haitians from abroad and the rest of the United States mostly through word of mouth. Haitians started arriving in Springfield by the thousands in recent years, filling jobs at local manufacturers, opening businesses and contributing to the economy. They helped turn around a city in trouble by reversing the population decline and telling families and friends about all that Springfield had to offer — good pay, inexpensive housing, and a safe environment.

“The revitalization of Springfield and its welcoming nature to Haitian migrants should be viewed as a success story,” Vignarajah of Global Refuge said. “It’s helped Springfield start a new chapter” that could have been an inspiring tale of immigrant success. Now, such hopes have been derailed.

Six days after former president Trump made his Haitian pet-eating comments, Springfield city officials reported that there had been more than 30 bomb threats to the homes of local officials, schools, and buildings. It isn’t clear exactly when those bomb threats occurred. They were all hoaxes.

Still, DeWine deployed the Ohio state police to help patrol the schools. Police from Cincinnati, 80 miles to the southwest, and the Ohio State Highway Patrol helped provide security for the Sept. 24 city commission meeting. Citizens who wanted to attend the meeting had to pass through metal detectors.

The Haitians, Vignarajah noted, aren’t the only ones in danger.

“Sen. Vance wants us to think that this is all just fun cat memes on the internet, but really, this is the same conspiracy-driven rhetoric that has led to mass shootings in El Paso, Texas; Buffalo, New York; and Pittsburgh in recent years. When elected officials dehumanize migrants and policy portrays them as an existential threat, they’re sowing the seeds of violence and stigmatizing an already targeted population.

“We can and we must do better.”

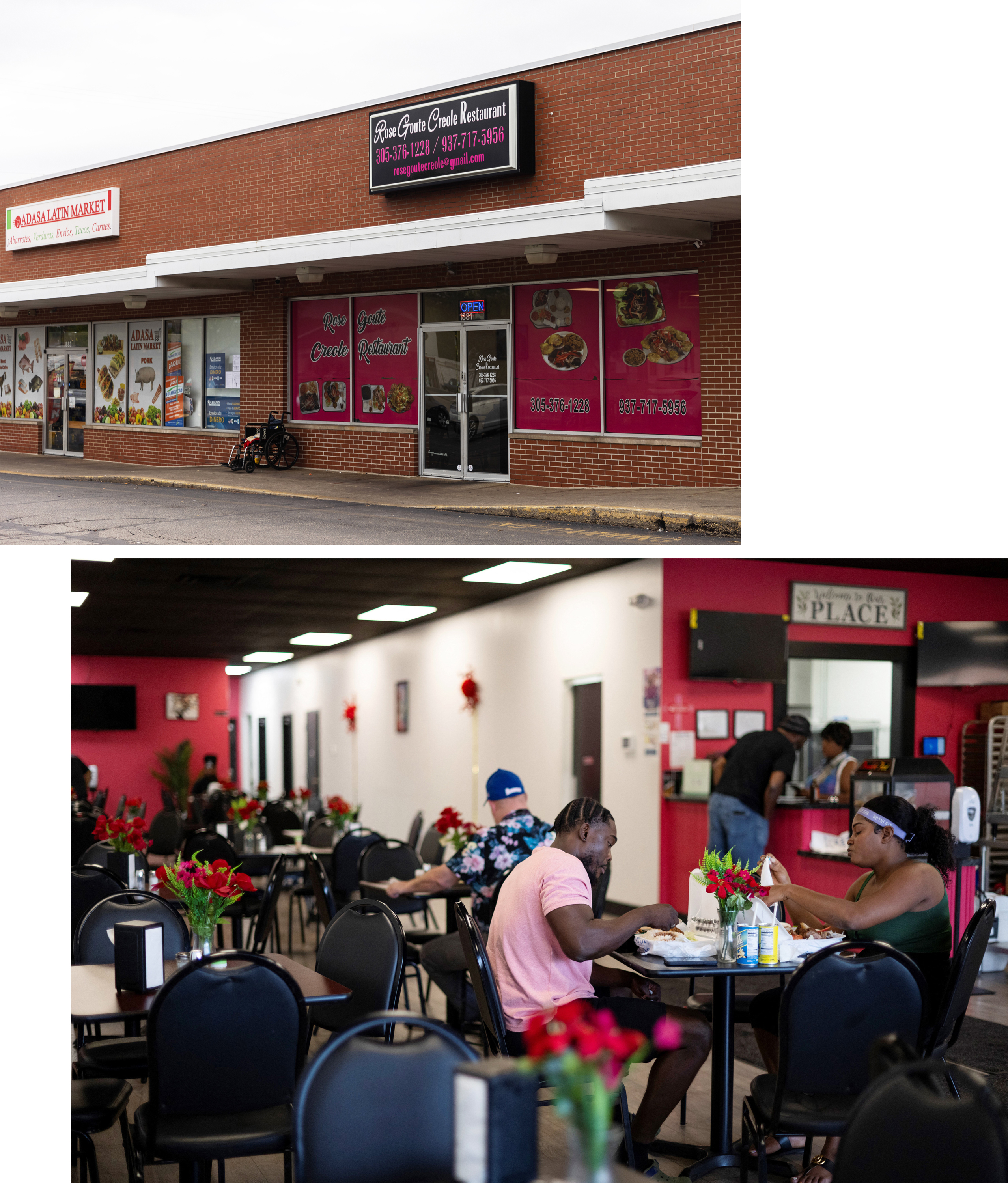

The Rose Goute Creole Restaurant is one of many Haitian restaurants in Springfield.

The Rose Goute Creole Restaurant is one of many Haitian restaurants in Springfield.

Top photo: Maddie McGarvey for Andscape. Bottom photo: Roberto Schmidt/AFP via Getty Images

“At work, they were under the impression that they had friends. Now they’re seeing they don’t,” Rock said. “I’m hearing that from adults. I can’t imagine what that feels like for a child.”

Springfield is still filled with tension, as evidenced by the increased police presence, locked doors and people electing to stay home. Trump has said he will go to Springfield, which to some residents said would be unhelpful given the climate.

There are some bright spots. The Rose Goute Creole Restaurant has been teeming with customers eager for a dish of diri kole (rice and beans) with chicken, griot (fried pork) or a Haitian patty, a flaky pastry filled with chicken and other options. On a recent visit, you could hear Creole, English and Spanish spoken by the diners. White and Black people said that they came to show their support during a time Haitians can use as much as they can get.

Chef Charly Pierre pays homage to Haitian street food in his New Orleans restaurantRead now

Chef Charly Pierre pays homage to Haitian street food in his New Orleans restaurantRead now

Vickie Coleman Gallagher, co-director of the Center for Refugee and Immigrant Success at Cleveland State University, said, “Everybody who touches or has a touchpoint with a newcomer is usually enriched. Their lives are enriched. The community is enriched, even when someone is skeptical.”

She noted that these experiences often lead to deeper relationships as people learn “about a different culture.”

“There’s just all these beautiful, unexpected outcomes to the community,” she said.

Over the last several weeks, it’s been hard for Springfield to focus on those unexpected and positive outcomes.

“I just wish people knew that for every fake story vilifying immigrants, there are thousands of true stories of resilience, belonging, and the tremendous contributions that these folks are making to this country,” Vignarajah said.

Ray Marcano is a lifelong journalist who has worked for some of the country’s biggest brands. He’s former national president of the Society of Professional Journalists, a two-time Pulitzer juror, and a Fulbright Fellow.