By Gary Fields,

The Associated Press

MEMPHIS (AP) — In a terrible way, the death of Tyre Nichols brings vindication to members of the Black community in Memphis who live in constant fear of the police.

Often, before, people didn’t believe them when told how bad it is.

The fatal beating of Nichols, 29, by five police officers tells the story many residents know by heart: that any encounter, including traffic stops, can be deadly if you’re Black.

Examples abound of Black residents, primarily young men, targeted by police. Some are in official reports. Anyone you talk to has a story. Even casual discussions in a coffee shop net multiple examples.

A homeowner who called the police because a young man who had been shot was on his front porch. The responding officers ignored the gunshot victim and entered the caller’s home. The caller was slammed to the ground and a chemical agent used on him as he was subdued. The officers then lied about the circumstances, but there was video.

A woman who lives in a “safe” northeast Memphis neighborhood yet says her 18-year-old son was hogtied and pepper-sprayed by police several years ago –- while she was with him. He became agitated after police arrived on the scene while he picked up his child from a girlfriend, triggering a mental health crisis, she said.

In police sweeps, unmarked cars roll into neighborhoods and armed plainclothes officers jump out, rushing traffic violators and issuing commands. The result is a community in fear, where people text, call and use social media to caution each other to stay inside or avoid the area when police operations are underway.

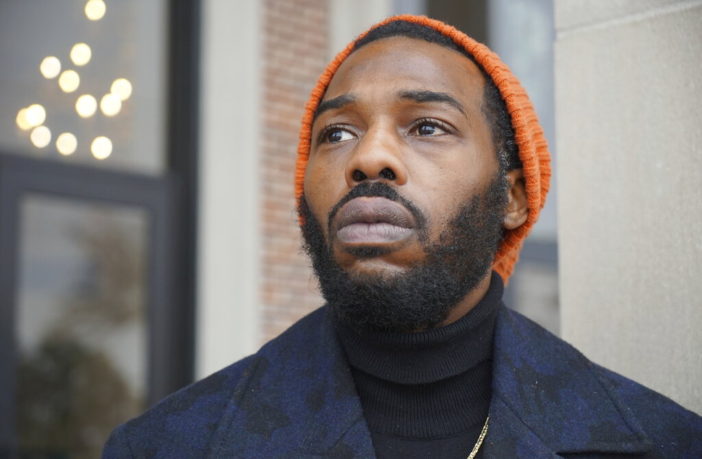

“There’s one type of law enforcement that keeps people safe, and then there’s a type of law enforcement that keeps people in check,” said Joshua Adams, 29, who grew up in south Memphis’ Whitehaven, home to Elvis Presley’s Graceland Mansion, now a mostly Black neighborhood.

If you are in the wrong neighborhood “it really doesn’t matter whether you’re part of the violence or not,” said Adams. “I’m less likely to be shot in a gang conflict than I am to be shot by police.”

Chase Madkins was about a block from his mother’s Evergreen neighborhood home just east of downtown Memphis dropping off his 12-year-old nephew when the blue lights of an unmarked police car flashed behind him.

Within seconds the officer ordered him out of the car and told him he made an illegal turn, and his license plate was not properly displayed because it was bent at the corner.

Madkins said the officer, dressed in tactical gear with his face covered and no visible identification, refused to give his badge number, unless he consented to a weapon search of the car.

Madkins, 34, consented, but called an activist friend to get to the scene.

“I had to remind myself, `Chase, this is how people get murdered, in a traffic stop,’” he said. To this day he does not know who the officer was.

The random stops are meant to terrorize, said Hunter Demster, organizer for Decarcerate Memphis. He’s the one Madkins called when he was stopped in November.

“They go into these poor Black communities and they do mass pullover operations, terrifying everybody in that community,” Demster said. Some people might think the officers are looking for murderers or people accused of heinous crimes, or have stacks of warrants for violent criminals, he said, but “that is not the case.”

People want more police, Demster said, but “what they’re really trying to say is we want more detectives looking for violent criminals.”

Marcus Hopson, 54, a longtime resident and barber in the neighborhood, said the sweeps remind him of how in the early 1990s New York focused on nuisance crimes and zero tolerance and that morphed into stop-and-frisk.

“It didn’t work then. It’s not going to work now,” said Hopson, who now splits time with a home in Mississippi. “You are terrorizing the neighborhoods.”

Black residents make up about 63% of the city’s population of 628,000. In many ways it is two cities: One is Beale Street and blues, barbecue and Elvis. The other is a spiritual center because of what happened here decades ago. There’s the Mason Temple where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous and prophetic speech proclaiming that Black people would eventually reach a world of equality. And there is the balcony at the Lorraine Motel, less than 2 miles away, where an assassin’s bullet killed King the next day and changed the future of Black life.

What that left here is complicated, especially when it comes to policing and crime. In 2021, the year the SCORPION unit – a specialty squad that all five officers involved in Nichols’ death were part of – was set up, homicides hit a record, breaking one set in 2020, the previous year. Homicides dropped in 2022 but high-profile cases kept crime in the news. Most of the victims those years were young Black men. In the cases where arrests have been made, the suspects were overwhelmingly Black.

“There are more officers in Black communities here because unfortunately we’ve seen a spike in crime in our communities,” said Memphis NAACP President Van Turner.

But adding police without addressing the underlying issues, including poverty, won’t help, he said.

“You have not resolved the systemic issues which create the crime in the first place,” Turner said.

The data also shows a disparity between the city’s population and who police target with force: Black men and women accounted for anywhere from 79% of use of force situations to 88%. The data doesn’t show how many of those people were being sought on a warrant for violent crimes.

The Memphis police chief has called Nichols’ death “heinous, reckless and inhumane.” The five Black officers accused of beating him were all charged with second-degree murder, and other officers and fire department employees on scene also have been fired or disciplined and could be charged. The SCORPION unit has been disbanded. The chief has ordered a review of all the special units.

Some people in the community are willing to give the police chief a chance to reform the department.

Marcus Taylor, 48, who owns a janitorial business and lives in south Memphis, urged officers in the precincts to come into their communities and network, “talk to store owners, go to barbershops, come to basketball games, and do it regularly. Get to know the people you are supposed to be protecting.”

“Come out without the lights flashing,” he said. “You’re out here to protect and serve, not beat up and whip. Everybody is not that hardened criminal.”

Madkins, who was among hundreds of people attending Nichols’ funeral on Feb. 1, said he wants to be hopeful. He heard the words of the Rev. Al Sharpton, who delivered a eulogy: “I don’t know when. I don’t know how. But we won’t stop until we hold you accountable and change this system,” Sharpton said.

“I felt affirmed. I felt seen and heard in my own struggle,” Madkins said.

The vindication, if you can call it that, comes too late for Tyre Nichols.

At the place where he was fatally beaten grows an unofficial symbol of violence and tragedy – a makeshift memorial with balloons and stuffed animals. It is around the corner from his mother’s home.

Nowhere seems safe for Black young men and boys.

When they start walking around the neighborhoods alone, or first start to drive, parents universally caution them on what to do when they encounter cops.

“This has to change,” said Erica Brown, 47, who described officers hogtying and pepper-spraying her son while she was with him. The memories of that day in 2014 kept her from watching all the video of Nichols being beaten. “Not just here in Memphis, but it needs to change nationwide.”

___

News researcher Rhonda Shafner contributed from New York. Also contributing were journalists Claudia Lauer from Philadelphia, and Adrian Sainz and Allen Breed from Memphis.