Written by Taneasha White-Gibson

James Baldwin: The life story you may not know

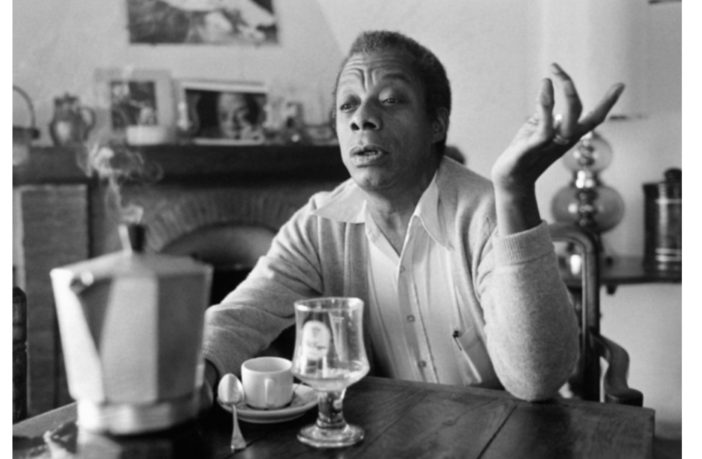

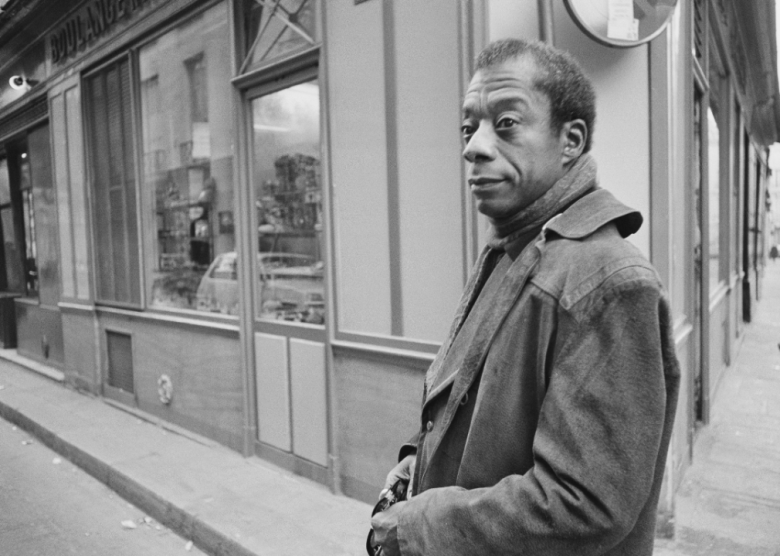

James Baldwin was a prolific writer, poet, essayist, and civil rights activist. Though he spent much of his life abroad, he is undoubtedly an American writer, whose works serve as a prism through which to view Black American life. Apart from being an esteemed literary talent, Baldwin routinely participated in the necessary criticism of both the U.S. and Europe’s mistreatment of Black people and broached the then-taboo issue of same-gender love and sensuality long before any widespread queer liberation movement.

Even in death, Baldwin’s unabashed critique and truth-telling made him not only a guiding light for his time but for this generation and those to come. Several of his prescient works—”The Fire Next Time,” “Notes of a Native Son”—were as vital during the Civil Rights Movement as they are now, a legacy carried on through the incantation of Black Lives Matter protests in the streets to the Black American lexicon proliferating college classrooms today.

Some may know the author’s interest in the arts started in childhood, but surprisingly, his journey to becoming a luminary originated in the pulpit. Fueled by humble beginnings and a desire to speak truth to power even amid an era of unthinkable violence and injustice against Black Americans, the Harlem-born literary giant traversed the world—from Switzerland, Paris, and Istanbul—with his name seen on the cover of playbills, memoirs, and photo essays, hoping to gain enough distance from his homeland to write about it. “Once you find yourself in another civilization,” he once told an interviewer, “you’re forced to examine your own.”

In his honor, Stacker compiled 25 facts and moments about the author, activist, and intellectual James Baldwin, using Biography.com, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and various other sources.

Topical Press Agency // Getty Images

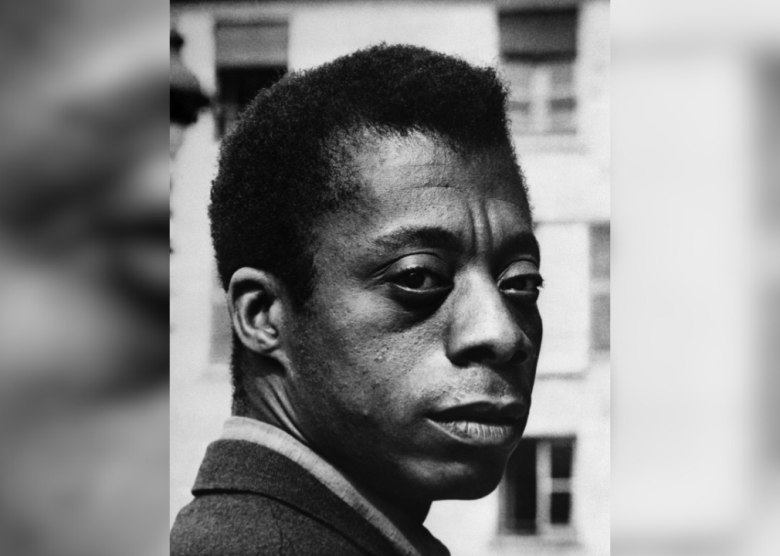

Born in 1924

James Arthur Baldwin was born to Emma Berdis Jones in Harlem, New York, on Aug. 2, 1924.

According to various accounts, his mother never shared details about his birth father—including his name. Jones later married David Baldwin, a minister, when young Baldwin was 3 years old.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

1938: Baldwin becomes a teen preacher

When he turned 14, the writer followed in his stepfather’s footsteps and became a teen preacher at Fireside Pentecostal Assembly during what he called a “prolonged religious crisis” in his 1963 nonfiction book “The Fire Next Time.”

Baldwin later left behind his adherence to Christianity, but his experiences at the church would inspire his 1953 novel “Go Tell It on the Mountain.”

Bettmann via Getty Images

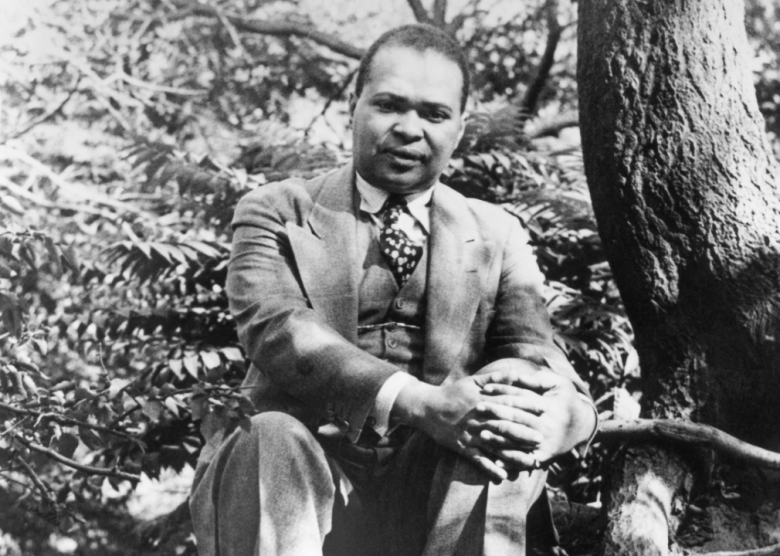

Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen was his middle school teacher

During his middle school years, Baldwin was a student of Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen. The poet worked as a French teacher at Frederick Douglass Junior High, where Baldwin was a student, ultimately opening Baldwin’s eyes to Black literature. Baldwin later became the editor of his school’s newspaper and eventually wrote a profile of Harlem from the point of view of multiple generations.

Carl Van Vechten Collection // Getty Images

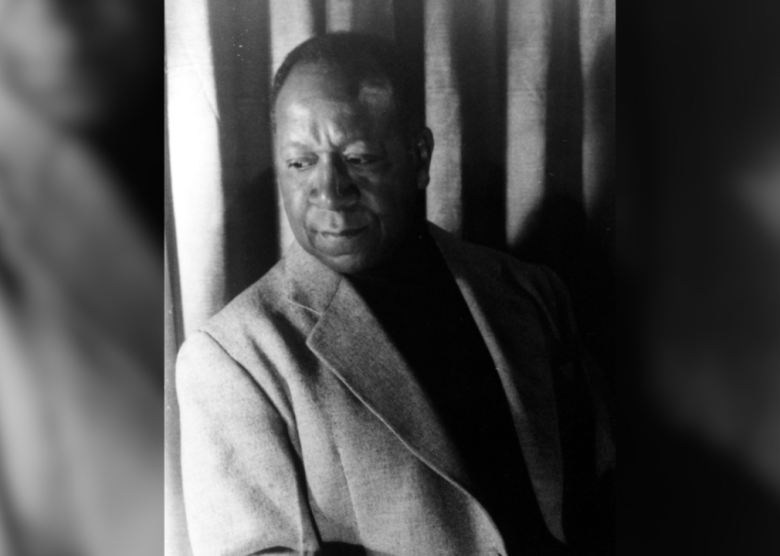

Mentored by Harlem Renaissance painter Beauford Delaney

At 16, Baldwin met painter Beauford Delaney, whom he regarded as a “spiritual father.” The artist would change Baldwin’s early conception that jazz was sinful, introducing him to the songs of Ella Fitzgerald and Bessie Smith. Delaney would also move to Paris five years after Baldwin, continuing their relationship. He later wrote that Delaney “was the first walking, living proof for me that a Black man could be an artist.”

William Cole // Getty Images

1942: Baldwin worked on a railroad after graduating high school

Despite an early interest in arts and literature, Baldwin was tasked with helping provide for his seven younger siblings, taking a job laying railroad tracks for the Army in New Jersey. While working, Baldwin experienced being refused service at restaurants and bars because of the color of his skin. He was soon fired, which led him to move to Greenwich Village.

CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

1944: Meets mentor Richard Wright by knocking on his door

Baldwin was introduced to his “literary father,” the late writer Richard Wright, after arriving unannounced at his front door. By this time, Wright had published “Native Son,” a tale of a Black man who accidentally kills a white woman and eventually rapes and murders his girlfriend while being pursued.

Wright read early versions of “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and helped secure a fellowship for Baldwin, which kick-started his career. About four years later, however, Baldwin would write critical reviews of Wright’s “Native Son” for the literary magazine Zero while in Paris.

Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos // Getty Images

1948: Leaves for Paris after his best friend’s suicide

According to a 1984 interview with The Paris Review, Baldwin feared for his survival as a Black man in the U.S. “My luck was running out,” he said. “I was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed. My best friend had committed suicide two years earlier, jumping off the George Washington Bridge.”

Baldwin shared with The New York Times that this move enabled him to write more freely about his experience as a Black man in America, saying: “Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I could see where I came from very clearly. … I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.”

Bettmann // Getty Images

1953: Releases ‘Go Tell It on the Mountain’

One of Baldwin’s first and more notable books, “Go Tell It on the Mountain” is a semi-autobiographical work about John Grimes, who grows up in 1930s Harlem under the influence of his Pentecostal minister stepfather. The novel covers the intersections of race, religion, and spirituality, paving the way for important conversations for which Baldwin’s later novels and essays would become synonymous.

Sophie Bassouls/Sygma via Getty Images

1954: Receives Guggenheim Fellowship

To aid in writing a new novel, Baldwin participated in the MacDowell writer’s colony residence in New England. During this time, he also won a Guggenheim Fellowship, both of which supported his later works.

Two years after accepting the Guggenheim Award, Baldwin published his second novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” which chronicles the struggle between race and sexuality and shows a character grappling between the love of a man and a woman all while navigating a white-dominated society.

Michael Ochs Archives // Getty Images

1955: Publishes ‘Notes of a Native Son’

Baldwin spoke about his admiration for Richard Wright’s 1940 book “Native Son,” which centers around race and the life of a Black man.

Following the success of his debut novel, Baldwin wrote “Notes of a Native Son”as an homage to the work. The collection of essays is a compilation of experiences surrounding race and social issues during the early days of the Civil Rights Movement.

In a New York Times review, esteemed Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes wrote of “Notes”: “Few American writers handle words more effectively in the essay form than James Baldwin. To my way of thinking, he is much better at provoking thought in the essay than he is arousing emotion in fiction.”

Sophie Bassouls/Sygma via Getty Images

1956: Publishes ‘Giovanni’s Room’

“Giovanni’s Room” received widespread acclaim and positive reception for exploring gay experiences, and many of Baldwin’s characters are within the LGBTQ+ community. This was years before the movement for queer liberation, and it proved groundbreaking. The book was a finalist for the 1957 National Book Award for fiction.

Bettmann // Getty Images

1957: Baldwin makes a trip to the South

After almost a decade out of the country, Baldwin returned to the United States amid the height of the Civil Rights struggle. He made a trip to the Deep South in 1957, which he later captured in “Letter from the South: Nobody Knows My Name” with the words, “Everywhere he turns … the revenant finds himself reflected.”

Bettmann // Getty Images

1961: Releases ‘Nobody Knows My Name’

While Baldwin was heavily involved in on-the-ground, behind-the-scenes efforts within the Civil Rights Movement, he utilized his literary talents and notoriety to speak on issues of Black folks in both the U.S. and in Europe. His book of essays, “Nobody Knows My Name,” compiles 23 works and earned the writer a spot on the shortlist for nonfiction at the 1962 National Book Awards.

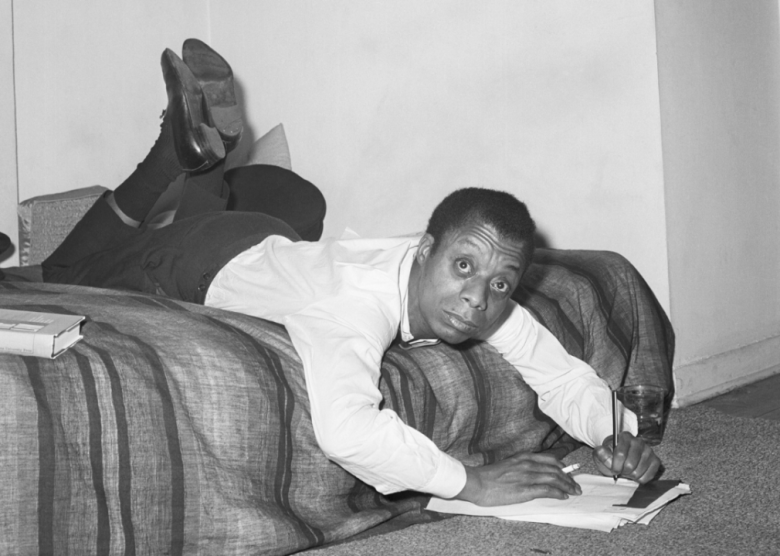

Walter Daran/Hulton Archive // Getty Images

1962: Baldwin’s feature in The New Yorker prints

The New Yorker published an essay from the writer on Nov. 9, 1962, entitled “Letter from a Region in My Mind.” The essay, which begins from his musings as a 14-year-old in Harlem and traverses through his experiences in his stepfather’s church and the Nation of Islam, was later expanded into a book.

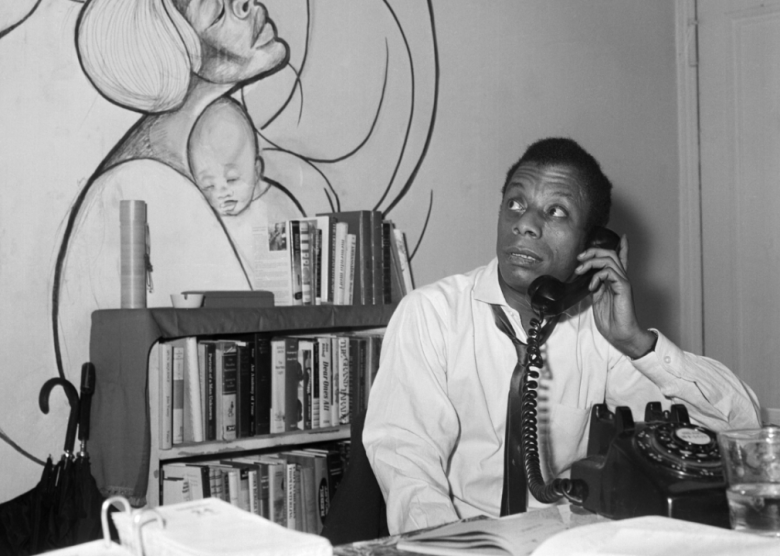

Marty Hanley/Bettmann // Getty Images

1963: Publishes ‘The Fire Next Time’

Originally a long-form article in The New Yorker, “The Fire Next Time”was published in 1963. Baldwin uses the two essays, “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of Emancipation” and “Down At The Cross: Letter from a Region of My Mind,” to speak candidly about the state of racism within the U.S. and Christianity’s role in American society.

The work became a bestseller and has remained a staple within African American literature. American author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates called it “basically the finest essay I’ve ever read.”

Robert Elfstrom/Villon Films // Getty Images

1964: Makes Broadway debut with ‘Blues for Mister Charlie’

Baldwin’s first Broadway production, this play presented an honest depiction of oppression loosely based on the murder of Emmett Till in 1955. In its preface, Baldwin wrote: “What is ghastly and really almost hopeless in our racial situation now is that the crimes we have committed are so great and so unspeakable that the acceptance of this knowledge would lead, literally, to madness.”

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Collaborates with Richard Avedon on ‘Nothing Personal’

Written as a tribute to his murdered friend, Civil Rights Movement leader Medgar Evers, Baldwin and his boyhood friend, American photographer Richard Avedon, created “Nothing Personal,” released in 1964.

Baldwin met Avedon while attending DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx. Avedon was one of the school’s literary magazine editors. The two fell out of touch after high school but reconnected when Avedon was commissioned to photograph Baldwin for Harper’s Bazaar and Life magazine. That shoot inspired “Nothing Personal,” which features photos from Avedon and 20,000 words from Baldwin.

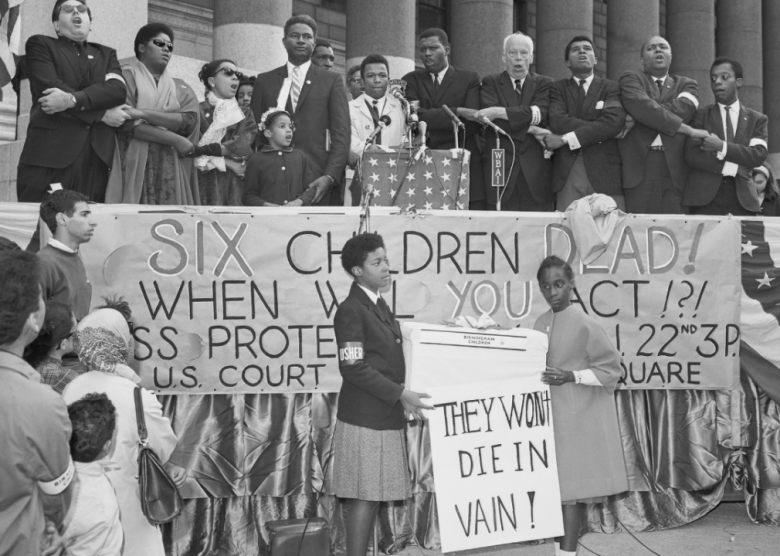

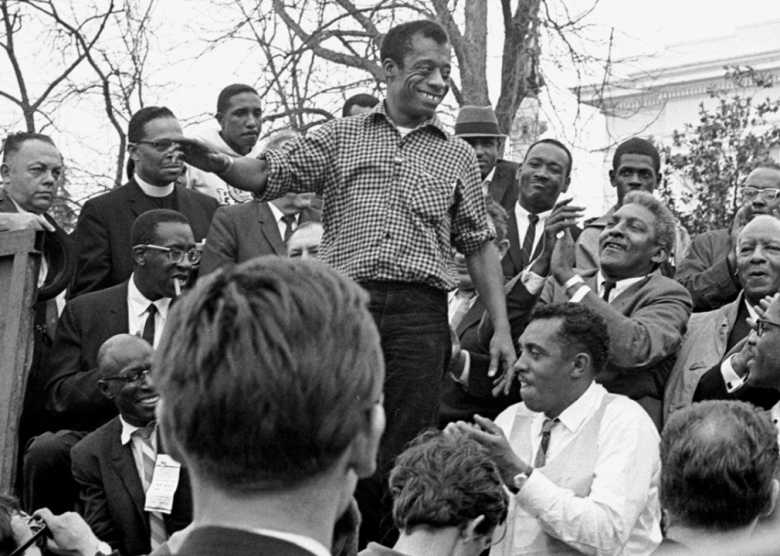

Robert Abbott Sengstacke // Getty Images

Baldwin attends 1965 Selma to Montgomery march

Baldwin was largely involved in social justice throughout the 1960s and participated in the March on Washington and the following Selma to Montgomery march and actions in 1965.

He was close friends with Bayard Rustin, another openly gay Black man in the movement, and both were active behind the scenes due to the ongoing prejudices surrounding the LGBTQ+ communities.

Sophie Bassouls/Sygma via Getty Images

1965: ‘The Amen Corner’ opens on Broadway

Apart from authoring books, Baldwin was a talented playwright and used the stage to discuss racial issues. “The Amen Corner,” about a woman evangelist, was heavily influenced by Baldwin’s religious upbringing and first performed in New York City.

While New York Times reviewer Howard Taubman noted the play’s slow pace, he wrote that the production “has something to say. It throws some light on the barrenness of the lives of impoverished Negroes who seek surcease from their woes in religion.”

kpa // United Archives via Getty Images

1968: Begins drafting Malcolm X screenplay

Baldwin moved to Los Angeles after being hired to write the screenplay for a movie about Malcolm X. According to writer David Leeming’s 1994 book “James Baldwin: A Biography,” “The first treatment he composed was a manuscript of more than 200 pages that read more like a novel than a screenplay. Furthermore, his presence was disruptive, his working habits deplorable, and his lifestyle expensive.” To Baldwin, however, he was subjected to 16 months in a foreign land called Hollywood, where people did not speak his language.

Baldwin eventually left the project, though he published his script under “One Day When I Was Lost” years later. In 1992, Spike Lee adapted the script that Baldwin and, later, Arnold Perl worked on, which became the film “Malcolm X,” starring Denzel Washington.

Jack Sotomayor/New York Times Co. // Getty Images

Baldwin helped Maya Angelou get her first autobiography published

Depressed by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Maya Angelou was invited to a dinner by her friend Baldwin. Her storytelling skills impressed cartoonist Jules Feiffer and his wife, Judy, which resulted in an introduction to his editor, Robert Loomis. This, with a little behind-the-scenes counseling from Baldwin that got Angelou to agree to an autobiography, led to the release of her seminal 1969 book “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”

Sophie Bassouls/Sygma via Getty Images

1976: Releases ‘The Devil Finds Work’

Baldwin is known for his poetry and creative nonfiction, but he was also a renowned film critic. His book-length essay “The Devil Finds Work,” which The Atlantic called “the most powerful piece of film criticism ever written” in 2014, juxtaposes race within the U.S. and cinema, covering such films as “The Heat of the Night,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” and “The Exorcist.”

Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

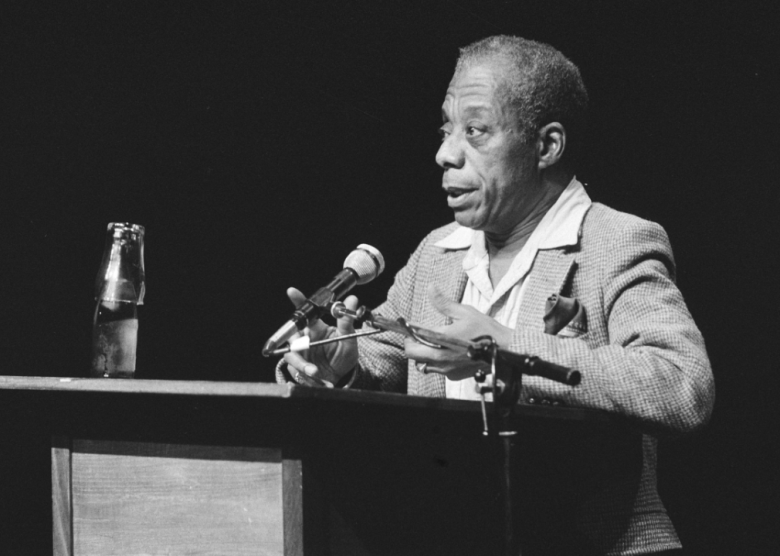

1983: Begins teaching at universities

While Baldwin continued to write until later in life, he also divided his time between teaching at the collegiate level—first at Hampshire College in 1983, then at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst—before returning to France in 1986.

At school, he became well known for his late-night discussions and drinks. He frequently remained awake even as his colleagues drifted to sleep, earning him his own time zone, called “Jimmy Time.”

Afro American Newspapers/Gado // Getty Images

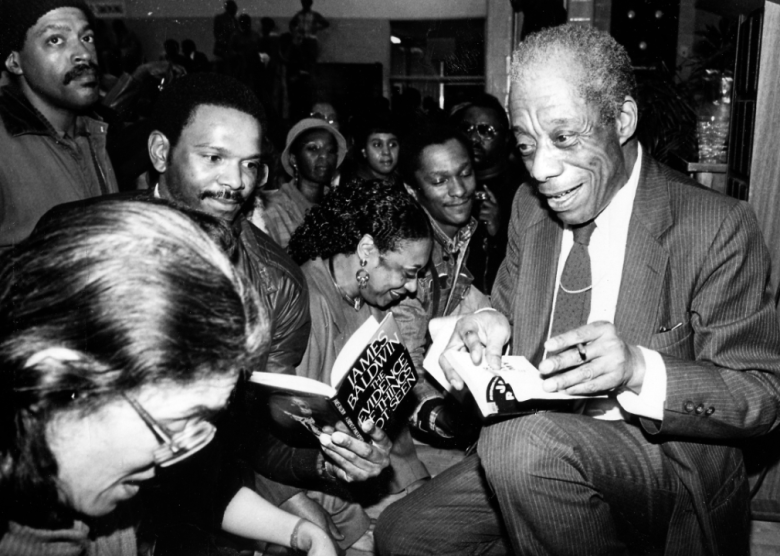

1985: Investigates ‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen’

Between 1979 and 1981, at least 28 children, adolescents, and adults were killed in Atlanta. On assignment for Playboy, Baldwin wrote about these killings, known as the Atlanta child murders, in “The Evidence of Things Not Seen.” He writes about the racial aspect of the murders, for both the victims and the convicted assailant.

Ulf Andersen // Getty Images

Death

On Dec. 1, 1987, Baldwin died of stomach cancer at his home in southern France.

Before his passing, Baldwin was working on a piece called “Remember This House.” This unfinished memoir was a collection of his personal experiences with civil rights leaders, including his friends Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Nearly four decades later, this manuscript would serve as the basis for Raoul Peck’s 2016 documentary film “I Am Not Your Negro,” which took home the BAFTA Award for Best Documentary and was nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 89th Academy Awards.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.