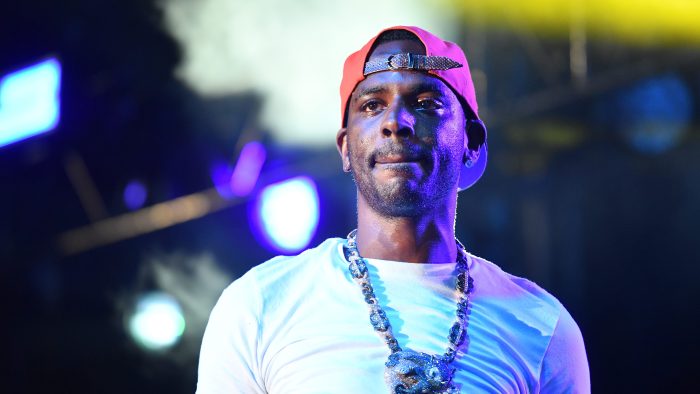

“It’s just like I gotta move right … The rap game ain’t nothing but the streets. What’s in the rap game? Supposed to be rappers, supposed to be street n—. In the streets, I ain’t never trust nobody … I know I got people that don’t like me. Plenty of ’em. This ain’t just started. I been having haters — big haters — since I was 15, 16.” — Young Dolph in 2017

If Beale Street could talk, it would tell you that as proud as Memphis, Tennessee, is, it’s a city that doesn’t shy away from its traumas either. At its heart rests a museum dedicated to the late activist Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement at the Lorraine Motel — the site where King took his final breath. More than a half-century later, and though not a means of comparison, the murder of rapper Young Dolph leaves its own considerable emotional wound.

On Thursday, after a four-day trial, a jury found Justin Johnson guilty in the November 2021 murder of Young Dolph at Makeda’s Homemade Butter Cookies. Johnson was also found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder and being a felon in possession of a firearm. As the verdict was read, Johnson showed no emotion upon learning the rest of his life would exist behind bars.

Ask many from Memphis about the impact of Young Dolph’s murder, and they’re liable to tell you that it’s a stain the city will wear for generations. Gun violence in Tennessee, particularly in Memphis, remains a polarizing issue despite its noticeable fatal results. The coronavirus pandemic did the city no favors, but the rush of violence failed to subside even after restrictions were lifted. Permitless carry was legalized in Tennessee in 2021, the same year Young Dolph became a name added to a grim list that’s only gotten longer in the years since.

Related Story

Young Dolph’s connection to Jackson State is deeper than footballRead now

Though Young Dolph was born in Chicago, his claim to rap fame is primarily associated with Grind City. His music was a direct reflection of the grittiness, darkness and swagger of the same streets that he survived and that ultimately took his life. His demeanor was country smooth and big-city Southern slick. And as it directly related to Memphis, it was the city, as Young Dolph would often tell anyone who’d listen, that turned him into a Southern hip-hop deity.

Johnson’s conviction is a victory of sorts as Young Dolph’s family received justice. Carlissa Thornton, his sister, spoke immediately following the verdict, thanking the court, the Memphis Police Department and her brother’s legion of fans for their dedication and support. But she did so while fighting back tears. Justice has never equaled peace. Justice has never reversed time and resurrected loved ones. As important as it is, justice has never been a match for senselessness. The speedy trial was a master class in justice and yet another brutal example of the crippling weight of gun violence in America.

Cornelius Smith, who pleaded guilty to murdering Young Dolph’s murder. His testimony in Johnson’s trial proved to be the its most electric and emotional element. Not only did he point Johnson out, but he implicated the late Anthony “Big Jook” Mims, the older brother of fellow Memphis MC Yo Gotti, as the mastermind behind the hit. Though Young Dolph and Yo Gotti were once cordial and Yo Gotti attempted to sign him to his record label, Young Dolph’s Paper Route Empire label had been engulfed in a yearslong beef with Yo Gotti’s Collective Music Group (formerly Cocaine Muzik Group). The animus included records (headlined by Young Dolph’s venomous “Play Wit Yo B—-”) and long-standing rumors of Yo Gotti being involved in multiple attempts on Young Dolph’s life, including a 2017 shooting at CIAA Weekend in Charlotte, North Carolina, where Young Dolph’s SUV was reportedly shot at more than 100 times. The act led Young Dolph to directly address the targeting on the aptly titled “100 Shots” from the aptly titled album Bulletproof. Mims placed a $100,000 bounty on Young Dolph before he was killed in a shooting in January, according to Smith.

Justin Johnson enters court to listen to the verdict in the killing of rapper Young Dolph, in court in Memphis, Tennessee, on Sept. 26.

Justin Johnson enters court to listen to the verdict in the killing of rapper Young Dolph, in court in Memphis, Tennessee, on Sept. 26.

Mark Weber/Daily Memphian via AP, Pool

Johnson’s attorney, Luke Evans, argued his client was not guilty of the charges, and it couldn’t be definitively proven he was at the scene of the slaying. The prosecution countered with video and cellphone evidence that supported Smith’s claims, including calls between the two before the slaying. Johnson and Mims also spoke immediately after the slaying. Those are the legal facts that the jury found irrefutable. What matters here — and what will permanently itself in Memphis’ painful history of matters involving just this — is just how asinine the entire scenario is.

In the trial, it was reported that Smith was offered $100,000 to kill Young Dolph, but that he was only paid $800. Hitmen being shorted money is no new phenomenon. Duane “Keefe D” Davis, who has been charged in the murder of rapper Tupac Shakur in 1996, has claimed for decades that Sean “Diddy” Combs placed a million-dollar hit on Shakur and former Death Row Records CEO Suge Knight — but was never compensated. According to former Los Angeles Police Department detective Greg Kading, Knight then, in turn, placed a $25,000 bounty on The Notorious B.I.G. that was split between his girlfriend at the time and Wardell “Poochie” Fouse (who died in a drive-by shooting in 2003). It’s unclear if the total amount was ever paid out. On Aug. 12, rapper Nipsey Hussle’s older brother, Samiel Asghedom, insinuated Eric Holder was sent to carry out the hit. Young Dolph, it seems, joins that unfortunate community.

Killers turned on each other on the stand, with Smith presumably telling what he knew for some sort of future grace when he stands trial for the same crime. Young Dolph’s family looked on, and an entire city received a more transparent, more painful view of how much it lost on Nov. 17, 2021. It’s easy to say, or perhaps more comforting, that Young Dolph “died over nothing.” The truth is he did die over something.

Related Story

Young Dolph’s memorial service was fit for a Memphis titanRead now

Young Dolph’s memorial service was fit for a Memphis titanRead now

Young Dolph died over street politics that all too often are solved with bullets instead of even the faintest sense of brotherhood. Young Dolph died over pettiness. Young Dolph died over a promise of money and a record deal that would never come (Johnson, whose rap moniker is Straight Dropp, was reportedly seeking a deal with Yo Gotti’s label). Young Dolph’s death is a microcosm of gun violence and how it affects far more than just the Black community. Watching Young Dolph’s trial was a reminder of just how deep the illness runs and how so many would prefer anything but a cure. Someone took to Johnson’s Instagram Stories moments after the verdict was delivered. “These n—as taking criminal responsibility. I’m taking street responsibility regardless I’m foreva the biggest they can throw away the keys before I ever eat da cheese,” the social post read.

Young Dolph’s life was taken — even more importantly, two kids lost their father — over this sort of mentality. It’s not uncommon, and that’s the tragedy. Once the headlines fade and Johnson’s name is etched in history as a robber of the worst regard, he’ll have to reckon with that mentality being the reason his life, effectively, is over, just like the man he foolishly agreed to murder. That short time that it took to put 22 bullets in Young Dolph will replay in his head for the rest of his life. As time passes, he’ll realize just how injudicious a decision it was. To pull the trigger but to inherit another party’s beef when his future was likely far from their list of priorities. This trial represented the value of Black life and the weight of Black responsibility.

In his 2014 street classic, “Preach,” Young Dolph spoke of a mentality he saw in many in Memphis and beyond. It was a defense mechanism, in hindsight. He didn’t know who Justin Johnson or Cornelius Smith were, nor did he know them in the final moments of his life. Yet, Young Dolph understood the same streets his music spoke for — the same music that drew from the animosity that sprouted from generations of economic disinvestment, overpolicing and an influx of drugs and guns — was perilous and that so before him had become ghosts. Out here in these streets, it ain’t no such thing as love (Preach), he rapped. The only thing I trust is this pistol and these slugs (Preach).

Those lyrics and so many others in his catalog provided the trial’s unofficial soundtrack. The truth is that we may never hear Justin Johnson’s name again. His name will effectively be, pun intended, “straight dropped” from cultural consciousness save for the moments that revolve around Young Dolph’s legacy. He’s not as much a villain as he is a casualty of a genuinely American sin. One man dies with air in his lungs while the other lives forever to never breathe again. The only more painful irony is those left to pick up the pieces of the picture that will never be whole again.

Justin Tinsley is a senior culture writer for Andscape. He firmly believes “Cash Money Records takin’ ova for da ’99 and da 2000” is the single most impactful statement of his generation.