Growing up in Newport News, Virginia, in the 1980s and 1990s, Michael Vick didn’t have much of an understanding of elections and voter rights.

Through his parents, Vick understood the magnitude of selecting leaders in this country, particularly the president, but the former NFL quarterback was surrounded by violence and poverty in his hometown (nicknamed “Bad News” because “a lot of bad s— happens there,” fellow native Allen Iverson once said). Vick’s lone concern as a youth was making it to the NFL and getting out his condition, so things such as voting or legislation took a backseat.

A federal conviction for dogfighting in 2007 sent him to prison for 21 months, which further distanced Vick from the electoral process and the desire to exercise his right to vote.

“At a young age I lost my rights to even be involved,” Vick told Andscape. “So for a long time I was just distant from it, didn’t pay any attention to it because it didn’t mean anything.

“It had no effect on me.”

While in prison, Vick made a list of things he wanted to accomplish after he was released, which included voting for the first time. In 2020, more than a decade after his release, Vick had his voting rights restored, paving the way for the then-40-year old to cast his first ballot that year.

In the lead-up to the presidential election Tuesday, the former dynamic playmaker is advocating for others to register to vote and have their voices be heard as well. He partnered with “Vote or Else,” a campaign to get more Black communities engaged in the political process to improve their social standing beyond the four-year election cycle.

“People didn’t do that for us when we was growing up,” Vick said. “So this is a campaign I felt like if somebody’s watching me and they’re idolizing me in a certain way, then they could look at all the things I’m doing outside of the game of football.”

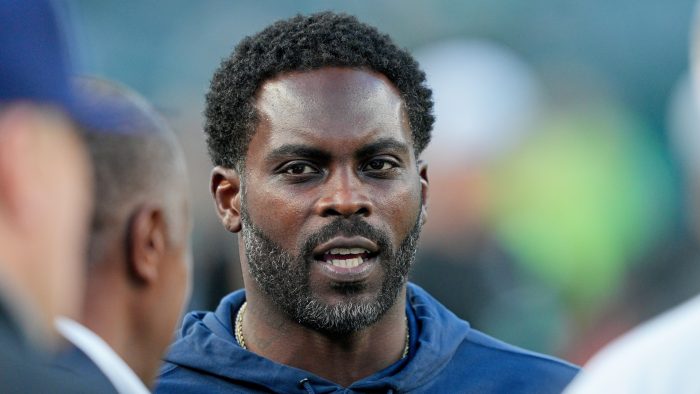

Former NFL quarterback Michael Vick walks door-to-door as part of a voter initiative by the organization Mobilize Justice on Oct. 10 in Philadelphia.

After an electric, two-season collegiate career at Virginia Tech that included a national championship berth and third-place finish in the 1999 Heisman Trophy voting, Vick was drafted No. 1 in the 2001 NFL draft by the Atlanta Falcons, making him the first Black quarterback to be taken with the top pick. It took just one season for Vick to become one of the most exciting and unique players in league history, mixing sprinter speed with kick returner elusiveness and a cannon for a throwing arm.

His 46-yard scramble in a game against the Minnesota Vikings during his second season, in which Vick’s lightning speed caused two defenders to run into each other when trying to tackle him, felt like something out of a movie. In his playoff start in 2002, he traveled to Lambeau Field to face the Green Bay Packers, who hadn’t lost a home playoff game since 1933. In 31-degree weather, Vick made something out of nothing on almost every play, leading the Falcons to a 27-7 upset.

From there, Vick became a cultural icon. Nike gave him his own signature shoe line, the first for an NFL quarterback. His Madden 2004 video game cover, and his nearly indestructible character play in the game, is one of the touchstone covers of an entire generation of gamers, still talked about to this day. Both in his play and how he looked (dark skin, cornrows hairstyle, streetwear), Vick presented a cool that was more present in the NBA at the time than the NFL. Wearing a Falcons jersey backward with Vick’s name and No. 7 on the back was a trend, and while he basically only stood around in the music video for Atlanta rapper T.I.’s single “Rubber Band Man,” in 2004, his mere presence was a moment in and of itself.

“Michael Vick was our football’s Michael Jordan,” Marvin Bing, the founder of Mobilize Justice in Philadelphia, which organized the “Vote or Else” events, said. “It was Jesus on the gridiron.”

Stanley Nelson discusses his 30 for 30 documentary on Michael VickRead now

Stanley Nelson discusses his 30 for 30 documentary on Michael VickRead now

Vick signed a 10-year, $130 million contract with the Falcons in 2004, a record amount at the time, but by April 2007 he was being investigated for running a dogfighting ring out of several of his Virginia homes for six years. By July 2007, Vick was indicted by a federal grand jury, and on Dec. 10, 2007, he was sentenced to 23 months in prison. (In September 2007, Vick was also indicted on two state dogfighting charges in Virginia; Vick pleaded guilty in that case and received a three-year suspended sentence.)

After serving 19 months in prison — where he refused to eat for the first three days he was there, missed the funeral of his grandmother, and witnessed things, he told an ESPN reporter at the time, things “that should stay in prison” — Vick was released in July 2009. Within weeks of his release, and after consulting with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell, Vick signed with the Philadelphia Eagles as a backup to Donovan McNabb that season before becoming the starter for the 2010 season. Vick’s stellar play resumed — he had a historic 400-yard, six-touchdown game against the Washington Redskins on Monday Night Football in 2010— and he later signed another $100 million contract with the Eagles in 2011.

Michael Vick watches the game between the Virginia Tech Hokies and the Boston College Eagles at Lane Stadium on Oct. 17 in Blacksburg, Virginia.

Michael Vick watches the game between the Virginia Tech Hokies and the Boston College Eagles at Lane Stadium on Oct. 17 in Blacksburg, Virginia.

Ryan Hunt/Getty Images

As he was serving time from 2007 to 2009, Vick missed the election of then-Sen. Barack Obama as president. He was aware of who Obama was, since he read up on the election and watched the debates, but witnessing the historic election of the country’s first Black president made him feel more out of place in prison. So he decided to finally vote when he was free.

“Just on a small scale, I felt like it was something that would be major at some point,” he said. “It’s just about having your rights, [to]do certain things in life.

“I screwed that up and I wanted to at least fight for it, and if I miss then, at least I gave it a shot.”

But when Vick tried to vote in Florida in 2011 with friends and family, he found that he was ineligible to vote due to his felony conviction. Before 2018, Florida’s constitution permanently banned those who had been convicted of a felony from voting. (Vick owned a home in Broward County, Florida.) But in November 2018, Amendment 4 was passed by Florida voters, restoring voting rights to 1.4 million returning citizens like Vick. Months later, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis added a requirement in 2019 that those affected by Amendment 4 first repay any fines, fees and restitution before they could have their voting rights restored.

Though Vick had paid the nearly $1 million in restitution from his conviction, he still hadn’t registered to vote as of early 2020. He hooked up with the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, which works to restore voting rights to people who have completed their sentences for felonies and led the effort to pass Amendment 4, to both get his rights restored and raise funds to help other returning citizens pay off court fees. At the time, the coalition raised more than $4 million for fee payments, with some assistance from the More than a Vote campaign backed by Los Angeles Lakers forward LeBron James.

Michael Vick was the ultimate X factorRead now

Michael Vick was the ultimate X factorRead now

“[If] People can call you a felon, then that means they can treat you differently,” Desmond Meade, executive director of the coalition, said in a 2020 documentary about Vick’s voting journey. “We deserve to be treated with dignity and respect, and the best way you get it is by making your voice heard.”

Vick voted for the first time in November 2020, filling out a Florida absentee ballot from his home in California. “I felt like the younger generations seeing me do it, whether white, Black or indifferent, they’ll strive to do the same thing,” he said.

Across the country in Philadelphia, Bing was putting together a campaign for the upcoming presidential election Tuesday that would rely on people like Vick for support.

Aside from founding Mobilize Justice, Bing also served as national director of art at human rights organization Amnesty International USA and is the co-founder of Justice League NYC, which advocates for criminal and social justice reform. Bing’s father, Malik Aziz, was a Philadelphia civil rights leader who in 2000 successfully challenged a state law that barred returning citizens with felonies from voting.

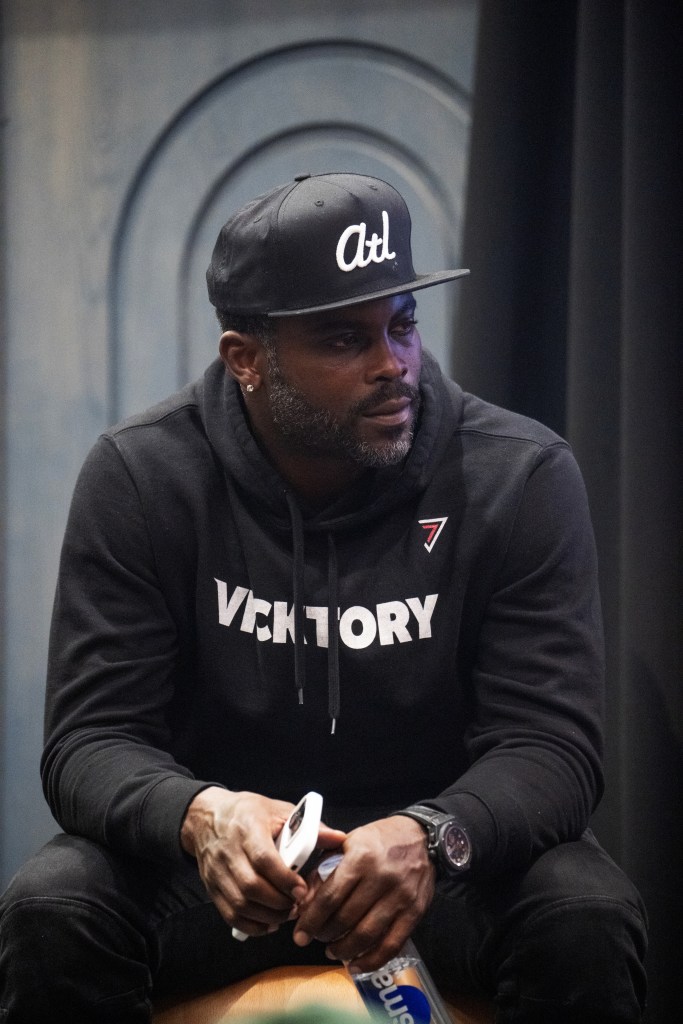

Michael Vick attends Vote Or Else town hall at The Gathering Spot on Oct. 25 in Atlanta.

Michael Vick attends Vote Or Else town hall at The Gathering Spot on Oct. 25 in Atlanta.

AP Photo/Rob Carr, File

“He was one of the first people to actually take the advocacy and partner with the organization to actually challenge the legal system in states to get voting rights when people come out of prison,” Bing said of his father.

For “Vote or Else,” Bing enlisted athletes and entertainers to engage with the Black communities that can feel forgotten between election cycles, and to advocate for collective change that improves their social condition. That list includes Vick and Iverson, rappers Beanie Sigel, Freeway, Jadakiss and Killer Mike, and actor Woody McClain, among others.

Bing said he chose these celebrities because their upbringings and backgrounds made them credible messengers.

“They come from what I consider ‘the mud,’ ” Bing said. “They know what it’s like to struggle, they know what it’s like only having that sport to get them out of their circumstance to change their family and [their]circumstance.”

Michael Vick’s next chapter includes forgiving himself and guiding young athletesRead now

Michael Vick’s next chapter includes forgiving himself and guiding young athletesRead now

Vick went around neighborhoods in Philadelphia and Atlanta knocking on doors, talking to residents, hugging them and taking photos to educate them on their right to vote and the importance of having their voices heard. A woman Vick met in Atlanta told him her father was a big fan of his, and hung his Falcons jersey on the wall.

“It continues to make me persistent and accomplish more in my life,” Vick said. “I’m not a young man, but I still got a lot of life to live, God willing, so I continue to set goals. People like that encourage me, hearing stories like that and people appreciating the little bit I did in my time there.”

Bing said Vick brings a unique perspective as an accomplished Black athlete, entrepreneur, husband and father who made it out of Virginia and the criminal justice system. Vick, who retired in 2017 after 13 seasons, speaks the languages of these Black communities, and his resilience over the past two decades is a sign of hope.

So much so that, according to Bing, Vick inspired at least one person in Philadelphia to do her civic duty.

“One woman said, ‘S—, I might go early vote right now,’ ” Bing said.

Martenzie Johnson is a senior writer for Andscape. His favorite cinematic moment is when Django said, “Y’all want to see somethin?”