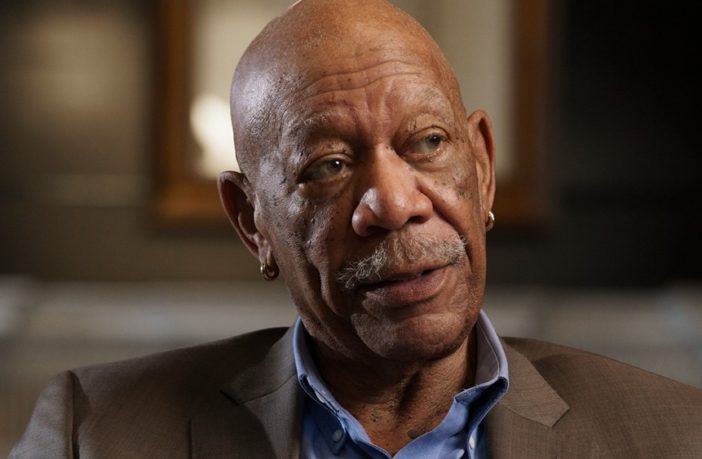

Academy Award-winner Morgan Freeman’s new documentary, 761st Tank Battalion: The Original Black Panthers, which he executive produced and hosts, tells the story of the first Black tank unit to serve in combat during World War II. The story is fascinating in the scope of these brave young men’s accomplishments in the 1940s as they fought against Nazi-occupied Germany. It’s also heartbreaking that their heroic efforts wouldn’t be heralded until three decades later.

Then there’s Freeman’s personal journey to learn about two of his uncles who were called to fight—much to his grandmother’s dismay—and the mystery of their whereabouts after entering the military. “There were a lot of times where guys got hit with a bomb or shell and they just disappear,” Freeman says about men who went to war. “They were just annihilated and there was no sign of them anywhere, maybe you’ll find a shoe.” Searching for answers and sharing stories of the men who trained at Camp Claiborne in Louisiana and fought for America is at the heart of this documentary.

Freeman and the film’s director Phil Bertelsen sat down with EBONY to talk about its inception, how America has largely ignored Black American’s contributions and whether the tide has turned for better or worse.

EBONY: What made you want to get involved with this project?

Morgan Freeman: A young man came to us with this idea about the 761st Tank Battalion. He had been looking into the situation and was starting to write about it. And it was all getting ready to be done when cooperate shifts happened. In situations like that, particularly in Hollywood, things that are on one shelf move to another. But then along came Phil Bertelsen.

Phil, tell me how you pulled this story all together.

Phil Bertelsen: It was Morgan’s passion that really drove us. And to learn that he had this mystery in his past with regard to his uncles that served, we were further motivated to really uncover the story about this history that’s been unwritten or erased: If Morgan Freeman doesn’t have a record of his uncles’ service, where does that leave the rest of us? It just tied into the story of the 761; all that they had to withstand to get there, what they faced when they returned home and their long-delayed recognition for their valor and honor. It’s that story that really drove the narrative.

You get a chance to chat with 98-year-old Captain Robert Landry, who actually served with the battalion. What was that like?

Freeman: It’s an everyday experience actually. Old soldiers are just old soldiers. They talk softly if they talk at all. His kids were there with us and they commented that while he was talking to us, they were learning more about him than they had learned in their lives as he came back from the war. That demonstrates that soldiers just can’t unload like that, to come back and start talking about it. The idea of being in situations where it’s “kill or be killed” is extremely stressful. And that’s what adds to so much post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans. So many carry that burden and wake up screaming in the middle of the night because something recurred in their sleep.

Why do you think our nation often doesn’t recognize Black Americans’ contributions to our democracy and to our freedom?

Bertelsen: They say history is written by the victors and over the course of history, we haven’t had the opportunity to write our own story. Why we’ve been eliminated or underwritten I think is part of a larger scheme that doesn’t necessarily want to celebrate our contributions. When you look at books being banned and curriculums being revised to soften the blow of history, you begin to understand that history is uncomfortable and inconvenient to some. But it’s real history and immensely powerful and important, particularly for a younger generation to go forward with certain confidence and fortitude about where they come from.

What would you say to Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, who is trying to eradicate Black history from schools, about this being American history?

Freeman: You don’t want to know…It would not be good. But it includes the word “going.”

Has fighting for our country since the Civil War finally earned us equality as Black Americans?

Freeman: I think equality is here. I can’t complain about my life. Nobody white ever held me back that I know about. I know that we’ve grown up in a country where systemic racism guides it, but that’s being overcome daily. I think that one thing we have always had to overcome is the idea of maintaining docility because the thought is: how can people who have been enslaved not kill everybody if they get a chance? We’ve had many, many chances to do things like that. That’s why they never wanted to put us under arms or keep us under arms after we were used for whatever conflict was going on in America. Because one of these days—and I’m thinking in a white mind now—one of these days they’re gonna rise up as we wouldn’t be held down like that. I’m pretty sure that one of these days if we don’t watch out, we’re going to look around and there they are all going to be. That’s an unfounded fear. There have been small groups that have tried. But after being here for generations, it’s not in us. We, as Americans, have been here as long as anybody else and we’ve added whatever the country needed and we’ve held the place together.

How can we honor these men and keep these stories alive?

Freeman: What can we as individuals do to keep these stories alive? Proselytize. Here’s an installment on the activities of this group in World War II: Talk about it.

Bertelsen: So much of our history as African Americans is an oral history. And it’s incumbent on us to hand that down regardless of the trauma or the brutality that may have grown out of it. There’s a reason to share where we’ve come from so that future generations can continue to tell that story. So talk about it.

761st Tank Battalion: The Original Black Panthers airs Sunday, August 20 at 8/9c on the HISTORY Channel.