By Maya Pottiger,

Word in Black

It had been a crazy summer. And, at the end, Sharif El-Mekki was in tears.

He was watching students perform in their end-of-the-year showcase, showing off the singing, dancing, and cultural skills they had learned during the summer of 2019.

El-Mekki had worked in schools, both as a teacher and principal, for 26 years. And, after piloting a program in 2018, he left his job to pursue full-time what is now the Philadelphia-based Center for Black Educator Development, with the mission of creating a more sustainable Black educator pipeline.

“It was deeply emotional for me,” El-Mekki says.

The nature of the day was giving in to that type of emotion, says Shayna Terrell, managing director of program strategy at CBED. Terrell also co-founded CBED with El-Mekki after serving as his assistant principal in Philadelphia. During that 2019 showcase, she remembers seeing gratification: staff, students, and parents all appreciating the hard work.

“It was something that we went out on a ledge, and we did on our own,” Terrell says. “It was a wonderful high note to end our program on. And, for [El-Mekki], the showcase solidified that what he was doing was right. And this was the right place to be.”

According to the most recent data from the National Center for Educational Statistics, only seven percent of K-12 public school teachers identify as Black. So it’s no wonder El-Mekki remembers thinking about how many students don’t have the experience of people believing in them in a way that provides students space and guidance to lead.

“To be able to see all of that come to fruition was a bit overwhelming,” El-Mekki says. “It also steeled my spine because it gave me even further fuel to keep moving forward.”

DSC_0630: Freedom School Literacy Academy.

(Photograph courtesy of Trent Petty)

Planted seeds, growing

The idea for the Center for Black Educator Development didn’t come to El-Mekki in a dream. Rather, pieces of it had been planted in his mind from a young age.

His own Philadelphia elementary school was an all-Black school, including the staff. “You can’t help but to be shaped by your experiences,” he says.

In his professional career, he found himself resonating with the connections between education and racial justice. And then, while doing a fellowship with the U.S. Department of Education, El-Mekki realized a lack of Black educators wasn’t just a problem local to Philadelphia, but one that existed nationwide.

One source of the problem is Brown v. Board of Education, which, El-Mekki says, is when the Black teacher pipeline started “having holes drilled in it and became pretty leaky.” In the years after the 1954 decision that made racially segregated schools unconstitutional, more than 38,000 Black educators lost their jobs. Even though these educators were highly skilled and qualified credential-wise, districts refused to hire them to teach white students or be school administrators supervising white teachers.

But the strongest source of his motivation to build a Black educator pipeline was the youth. El-Mekki recalled a student who told him they wanted to become a teacher but said there was nowhere to learn to teach. This is especially true for Black children, El-Mekki says, based on their own experiences.

The early pipeline work was key for El-Mekki, Terrell says, to inspire people to become teachers at a young age instead of waiting until they’re in college when it’s “too late.”

“That’s the gumbo pot that influenced the decision,” El-Mekki says. “But, ultimately, it was this idea of how do we rebuild a national Black teacher pipeline that’s sustainable, highly effective, predictable, and protected.”

He’d already been doing the work on nights and weekends through different initiatives, but he wanted to commit himself to it full-time.

A vision realized

In 2018, El-Mekki and Terrell ran a pilot program where Black high school students were teaching younger students. And it worked. Though El-Mekki was “blissfully happy” in his principal job, this presented an opportunity he hadn’t seen before.

“It was so compelling and so interesting,” El-Mekki says. “It also fed that desire that I had for more students to experience what I experienced as a youth with a school full of Black teachers that were totally committed to them, that understood their cultural background.”

And then they got a grant to fund CBED so he and Terrell took the leap.

Three models influenced CBED: Freedom Schools, Black Panther Liberation Schools, and Independent Black Schools. This was organic for Terrell, who had been in the Freedom Schools movement since she was 16.

In the summers, the Freedom Schools Literacy Academy is open to K-2 students, and there are three tiers of educator training. High school students work as teaching apprentices, gaining classroom experience and professional development. College students and paraprofessionals lead classroom instruction and hone their teaching skills. And professional educators serve as coaches, helping the others learn the trade.

It’s hard work, Terrell says, but it beats punching the clock day in and day out. Every day, she is surrounded by people who care about the growth and development of Black children.

“The experience of rebuilding a Black teacher pipeline, to me, is inspirational. It’s inspiring. It’s fulfilling,” Terrell says. “I feel like I’m getting up and I’m going to a job and, even though the work is hard, I feel fulfilled.”

Earning high marks

Before he got his teaching position, Trent Petty was seeking out like-minded educators, specifically focusing on Black teachers. And when he learned about CBED and its work, it seemed like the perfect match.

Petty first participated in the summer literacy academy in 2021, and then was a site lead in 2022, running daily operations at one of the schools. He came back because he felt like he was doing the groundwork and laying the foundations that CBED strives for: teaching and working with students in the same demographics he comes from, and both teaching them and watching them learn about Pan-African studies.

And now, Petty teaches second grade in North Philadelphia, a job he got after Terrell connected him for an interview.

“It’s helped me because it was like a preview before I became a full-time teacher,” Petty says. “It was just a really fun opportunity. And I got to meet a lot of other like-minded professionals, as well.”

And the students — and their families — enjoy it, too. El-Mekki isn’t the only person who has been moved to tears by CBED: At the end of the summer session, his daughter cried and wouldn’t stop hugging her teacher.

There was also a California-based student who participated virtually. She was warned that CBED starts the day at 8:30 in the morning eastern time — 5:30 a.m. on the West Coast — but she was adamant, despite the massive time difference. And she never missed a day, nor was she ever late.

“Many families say that was the best experience for [their]child,” El-Mekki says. On top of working on literacy, reading, and writing, they’re doing positive racial identity development.

“They’re saying, ‘I wish my regular school was this type of experience.’ For me, that really strikes me as an opportunity. We have to make sure, as a society, that it does not continue to be a missed opportunity for us, for so many children across the country.”

Reported progress

In 2022, CBED reached students at five physical sites — three in Philadelphia, one in Camden, New Jersey, and a pilot site in Detroit — and 13 states virtually. It also saw a 300 percent growth in the number of teacher apprentices, with 36 in 2019, its inaugural year, compared to 142 in 2022. In its entirety, CBED has worked with 388 teacher apprentices at all levels.

And, though the world shut down less than a year after CBED was launched, growth didn’t slow during the virtual months. Instead, parents had a demand, and CBED answered the call, Terrell says.

“Because schooling, at that point, was also happening in the virtual world, it gave some of our future apprentices the [experience]that they needed,” Terrell says. “To be able to practice how to teach in a virtual classroom was wildly successful.”

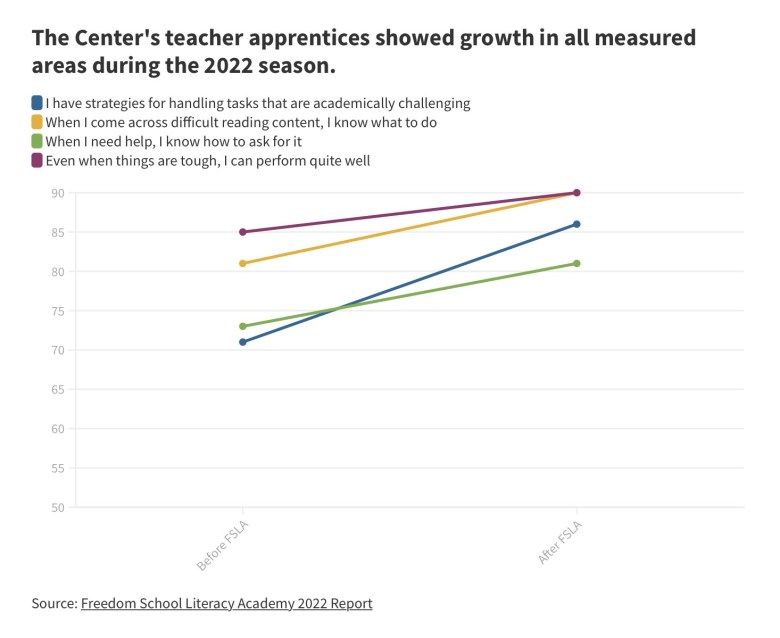

CBED has clear learning objectives for its teacher apprentices, wanting to make sure they are prepared for the classroom setting. The objectives aim to improve academic self-efficacy, mindset, habits of mind, and strategies for both academic and personal success.

In the most recent year, 2022, all four areas were met, according to the 2022 progress report. The biggest increase was in apprentices feeling they have strategies for handling academically challenging tasks, which jumped from 71 percent to 86 percent by the end of the summer.

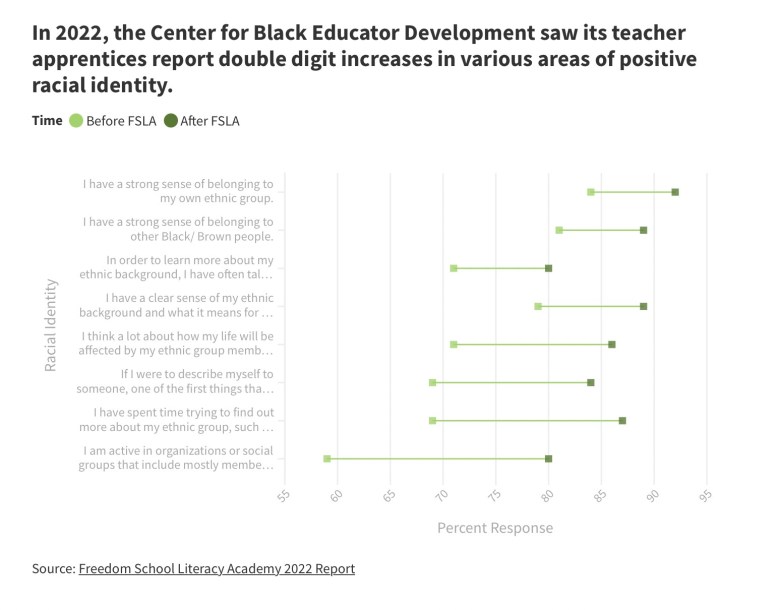

Plus, there were significant jumps in teacher apprentices reporting positive racial identity. The largest increase came with those reporting they are active in organizations or social groups that include mostly members of their own ethnic group, with a 21 percent increase.

And it’s proven to work. During the five-week program, 83 percent of the K-2 scholars improved their reading levels.

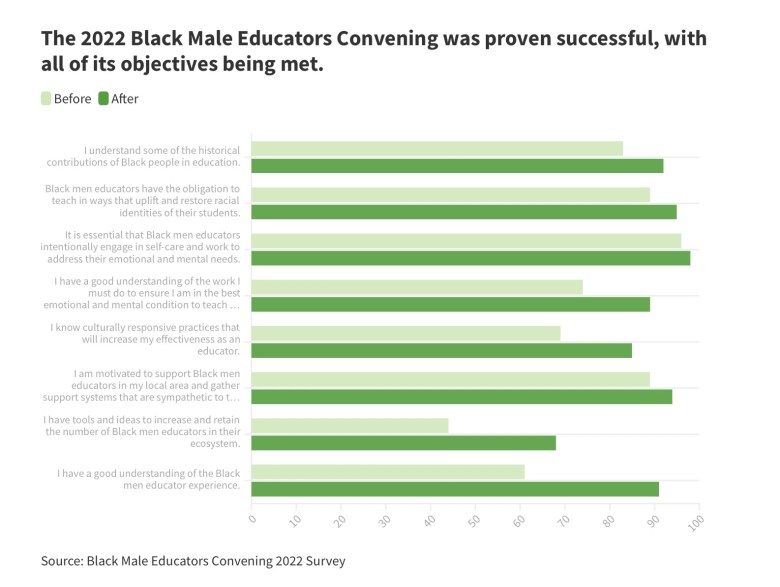

CBED’s commitment to building the Black educator pipeline extends beyond its day-to-day work. In November, the organization hosted the fifth-annual Black Men Educators Convening, which drew nearly 900 people to Philadelphia over its three-day span.

Looking at all of the progress and hearing success stories fuels Terrell.

“It pushes me further to figure out how I scale this so this happens for every apprentice who comes to our program,” Terrell says.

Three more years, and beyond

So what does the future look like?

In the next three years, Terrell hopes to expand to three more cities and increase the amount of programming in their current cities. She wants to be working with hundreds of apprentices and over 100 scholars.

“Our impact over the next few years will continue to grow,” Terrell says. “Hopefully, we’ll have a real steady placement system for our apprentices, meaning we can say we’ve placed over 100 teachers in the classroom over the next few years.”

CBED will soon expand to Memphis.

Expansion cities are carefully selected and must meet a host of criteria. For one, beyond the superintendent, there has to be a whole consortium of people committed to creating a Black teacher pipeline and believing it will positively impact the district, city, state, and region: community members, families, and students.

And people have to be committed to doing the entire program — developing both the talent and workforce development model. And, of course, there has to be funding and support.

More uniquely, El-Mekki wants students to be involved in the program, helping to solve a problem “that they had no hand in creating.”

“We have to envision a history of activism, because that’s how we look at teaching,” El-Mekki says. And there has to be “A desire and understanding of what it takes, that is a long term effort, not a short term initiative — that is a long term investment.”

Something else El-Mekki wants to continue prioritizing is professional learning to help influence the school ecosystem: school board members, curriculum writers and purchasers, instructional coaches, heads of schools, superintendents. Like the majority of teachers are white — and because the majority of teachers are white — the school ecosystem is often white, so El-Mekki wants to make sure the Black teacher pipeline also leads people here.

Overall, El-Mekki isn’t trying to rush, but make sure he’s helping to create a pipeline through sustainable and effective practices. He wants to make sure students understand this is how Black people have always been taught and learned, and the relationships between teaching and learning, and education and self determination.

And he’s already seen some of this come to fruition at his old school in Philadelphia, where at least five alumni have returned to teach various subjects, including art and math. And, of course, his 7-year-old daughter is “adamant” that she’s going to be a teacher one day.

“James Baldwin said hope is invented every day,” El-Mekki says. “And I firmly believe that every day gives me some type of inspiration.”