The sudden death of Hall of Fame running back Franco Harris on Wednesday sent shock waves throughout the NFL’s family of players, executives and fans.

Harris’ death at age 72 occurred three days before he was to be honored on the 50th anniversary of the Immaculate Reception, the most iconic play of NFL and Pittsburgh Steelers history. No one was more stunned or saddened than John “Frenchy” Fuqua, who spent five seasons as Harris’ teammate and backfield mate from 1972 when Harris was a rookie until 1976, Fuqua’s last season with Pittsburgh.

Like the Chicago Cubs’ legendary double play combination from Joe Tinker to Johnny Evers to Frank Chance, the combination of Terry Bradshaw to Fuqua to Harris became imbedded in NFL lore on Dec. 23, 1972.

“I did not believe it, I still can’t believe Franco’s gone,” Fuqua said during a phone interview. “I can’t believe it, man.”

I spoke with Fuqua on Thursday as he and hundreds of other former Steelers players and executives gathered in Pittsburgh to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the Immaculate reception and watch Harris’ No. 32 jersey become only the third Steelers jersey to be retired.

I got to know Harris through the prism of Fuqua, who was my teammate at Morgan State. We met in 1968, my freshman year at Morgan. Fuqua was a senior and had lost just one game in four years. His pro career would be a different matter.

He was drafted by the New York Giants in 1969. Fuqua was traded to the Steelers in 1970 and while he enjoyed individual success as the Steelers’ primary runner, the team lost: They finished 5-9 in 1970; 6-8 in 1971. Things turned around with the arrival of Harris in 1972.

Fuqua said he was overjoyed when the Steelers made Harris their first-round pick.

“When Franco came in, I moved to what I thought was my natural position; I was moved from fullback to halfback and had my greatest rushing year of my life,” Fuqua said.

Ultimately Fuqua was supplanted by Harris as the Steelers’ featured running back.

“I went from the No. 1 ball carrier to the No. 2, which didn’t hurt because I knew that would extend my career as a 5-foot-11-inch, 195-pound running back,” Fuqua said. “Franco extended my time.”

Joe Gilliam represented much more than ‘Pittsburgh’s Black Quarterback’Read now

There were no hard feelings, even though Harris replaced him as the lead runner.

“Yes, he did, but you know what? After four years in the NFL, you would like to extend your career as long as possible. And only the player knows when that time is coming. It was coming for me,” Fuqua said. “Franco was excelling. The thing that made Franco even more exceptional was not only could he run over you, but he could run around you as well. And you wouldn’t catch him if you got behind him. I didn’t complain at all. I say it was the perfect scenario for me.”

Their primary competition was off the field.

“We played chess, and if we really had a competition, it was on the chessboard,” Fuqua said. “I used to kick his butt.”

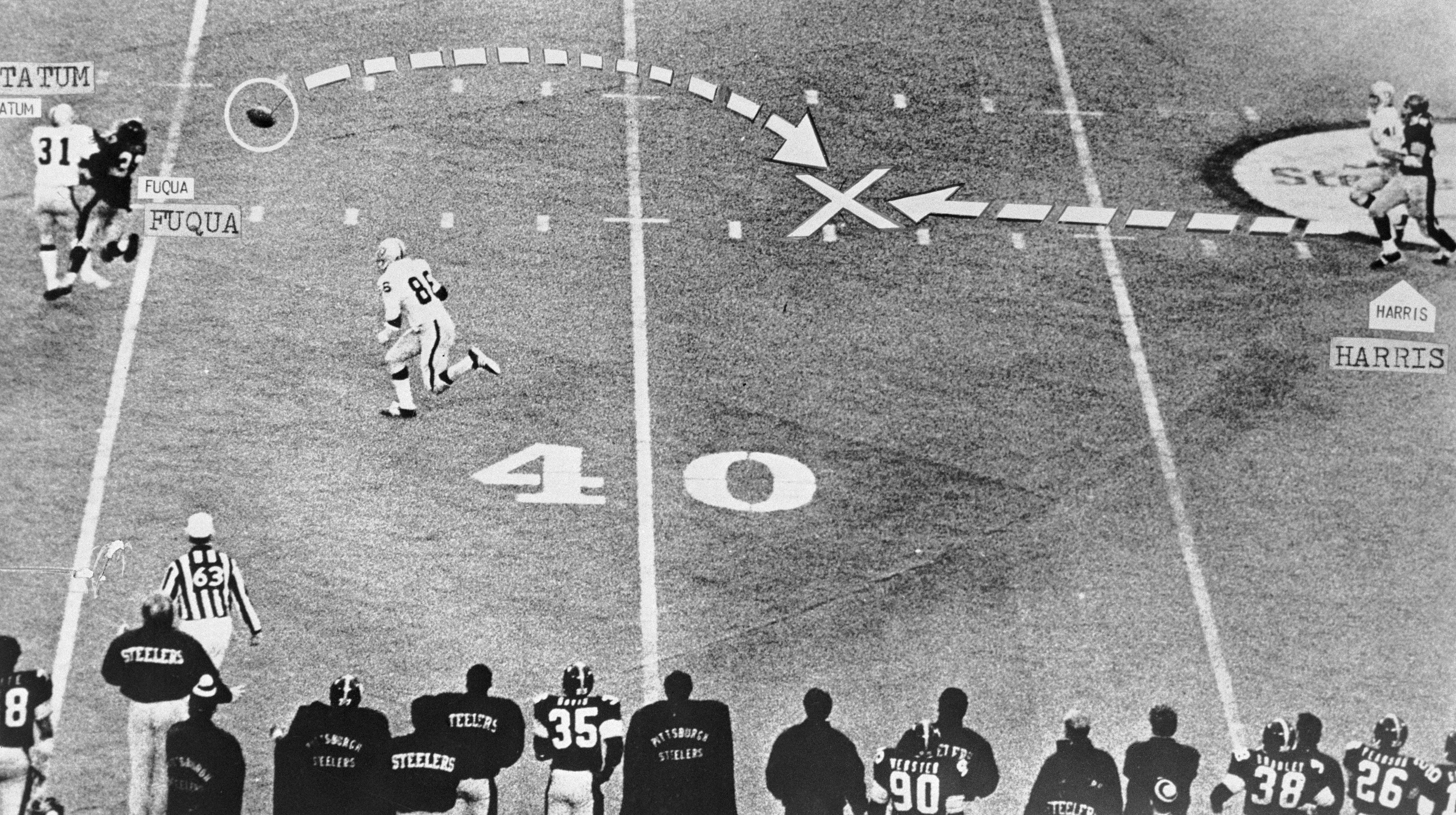

With 22 seconds left in the Pittsburgh Steelers-Oakland Raiders divisional playoff game, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw threw a fourth-down desperation pass intended for John “Frenchy” Fuqua (left). When the ball was deflected by Raiders safety Jack Tatum (left), it traveled seven yards into the arms of Franco Harris (right), who ran 42 yards for the winning touchdown.

With 22 seconds left in the Pittsburgh Steelers-Oakland Raiders divisional playoff game, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw threw a fourth-down desperation pass intended for John “Frenchy” Fuqua (left). When the ball was deflected by Raiders safety Jack Tatum (left), it traveled seven yards into the arms of Franco Harris (right), who ran 42 yards for the winning touchdown.

Bettmann

Fuqua and Harris won two Super Bowl titles as teammates: Super Bowl IX when Pittsburgh defeated the Minnesota Vikings and Super Bowl X when Pittsburgh beat the Dallas Cowboys.

But what they will forever be joined by is the final desperation play on Dec. 23, 1972, when Pittsburgh defeated Oakland 13-7 at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh.

The play has become one of the most enduring of all sports debates, matched only by whether catcher Yogi Berra tagged out Jackie Robinson in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series when Robinson famously stole home.

No one has ever established whether Bradshaw’s bullet pass hit Fuqua first or ricocheted off Jack Tatum, the Raiders safety who leveled Fuqua on the play. Under rules of the day, had the ball hit the offensive player — Fuqua — the play would have been whistled dead as soon as Harris touched the ball. The officials ruled, perhaps out of self-preservation, that the pass ricocheted off Tatum. Harris scooped it up and scampered in for the touchdown.

For 50 years, Fuqua has maintained that he knows but won’t tell. I thought I could coax it out of him when we spoke on Thursday.

“OK, I’m going to tell you, only because you’re an alumnus and a teammate,” he said. “I’m going to tell you.”

Fuqua paused.

“I’ll never tell.”

Franco Harris, the Immaculate Reception and an unlikely friendshipRead now

Franco Harris, the Immaculate Reception and an unlikely friendshipRead now

Pittsburgh’s victory over the Raiders became the foundation of the Steelers burgeoning dynasty. Fuqua had no idea that the play would be celebrated 50 years later.

“I had no idea, but you know what? I think that year, the Steelers put everything into it. We weren’t meant to lose to Oakland,” he said.

“Franco was a blessing, not only to the Pittsburgh franchise, but to his teammates, because that game gave the confidence and led us to four Super Bowl rings.”

Fuqua took pains to point out that his relationship with Harris — and Harris himself — was larger than the one iconic play. They enjoyed an enduring friendship from the time Harris entered the league.

“Oh, man, we were very close,” he said. “Franco would come by my apartment. He would bring his girlfriend at that time. His girlfriend and my wife got along great. We had a good relationship. All of the running backs, we would either meet at my apartment or Franco’s house, and we talked about football. We talked about private things, which we’ve continued to keep private over the years.”

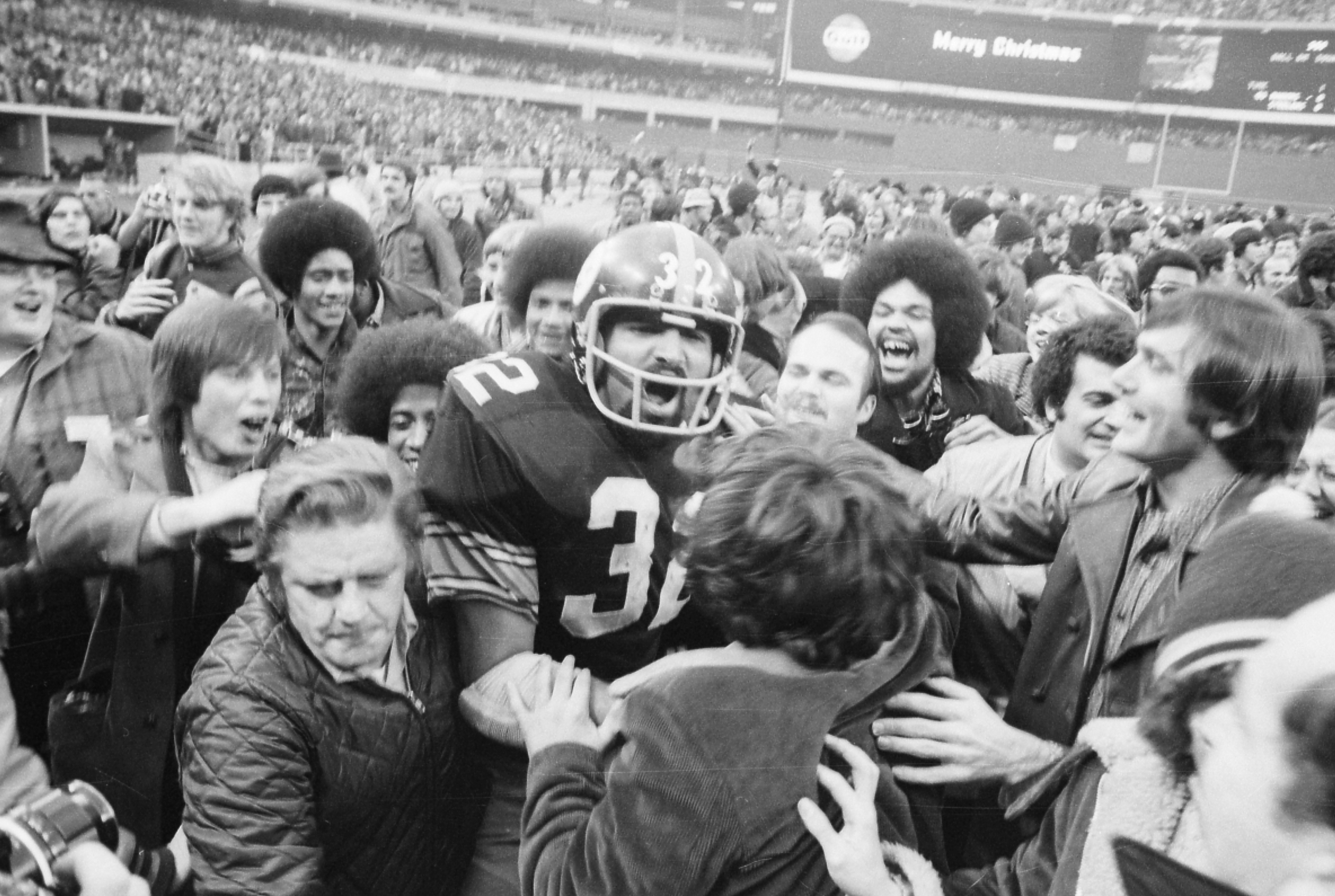

Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris (center) is mobbed by fans at Three Rivers Stadium after scoring the winning touchdown, nicknamed the “Immaculate Reception,” during the AFC divisional playoff game against the Oakland Raiders.

Pittsburgh Steelers running back Franco Harris (center) is mobbed by fans at Three Rivers Stadium after scoring the winning touchdown, nicknamed the “Immaculate Reception,” during the AFC divisional playoff game against the Oakland Raiders.

Bettmann

What impressed Fuqua was Harris’ commitment to keeping in shape and taking care of his body.

“He was a fanatic as far as eating the right foods, staying away from the foods you shouldn’t eat, and when we drank three to four beers, he only had one,” Fuqua said.

Fuqua recalled how Harris was always willing to give advice and counsel to young people, including Fuqua’s three children.

“Franco was compassionate,” Fuqua said. “I saw that with him. We did a lot of appearances. He took kids aside, while we were signing, and talked to them. I know it made a difference in their lives.

“I was with Franco for five years, and those years that I was with him, one of our promoters was Iron City Beer. Franco did not indulge. He started getting into shape one month after the football season. I said, ‘Man, you’ve got to rest on up,’ and he said, ‘Man, we’ve got to be in shape.’ You couldn’t ask for a more perfect football player, as far as away from the team, taking care of their body. I can testify to that. When we played cards, he would have a dumbbell sitting by, When he was trying to make a decision when he was playing [cards], he would lift it.”

As we wrapped up our conversation and Fuqua prepared to go to one of the many celebratory events, the finality and shock of his friend’s sudden death set in. Fuqua repeated what he said when we began our conversation. His friend of more than 50 years had died.

“Man, I still can’t believe Franco’s gone,” Fuqua said. “I can’t believe it. Franco was one of a kind.”

William C. Rhoden, the former award-winning sports columnist for The New York Times and author of Forty Million Dollar Slaves, is a writer-at-large for Andscape.