As absurd as it sounds, composer Quincy Jones had something to prove. For years, he had been meticulously conducting multi-studio sessions across the country for his most ambitious, genre-merging statement to date, 1989’s Back on the Block. Jones, who died Nov. 3 at age 91, was on a peerless run as a producer. Throughout the 1980s, the prolific polymath backed up his rep as the hit-maker’s hit-maker (1981’s The Dude); directed Michael Jackson’s coronation as the best selling artist of all time (1982’s Thriller); and helped guide Jackson’s follow-up album, Bad, to a record-breaking five consecutive No. 1 singles in 1987.

Yet Jones had no intention of trying to repeat previous commercial glories, the 75 million in album sales and 13 of his 28 Grammy Awards in the 1980s. With Back on the Block, Jones envisioned a concept album that combined Black musical expressions from Zulu chorus chants, jazz, and gospel to R&B, funk and the newest member of the family, hip-hop.

Just a few years earlier, Jones had plotted an unlikely 1987 collaboration between Jackson, dubbed the King of Pop, and hip-hop group Run-D.M.C. from Queens, New York, for an anti-drug song titled “Crack Kills” that never got off the ground. Jones believed rap, the young, controversial art form, deserved a seat at the table. So in the summer of 1989, he invited hip-hop artists Melle Mel, Ice-T, Kool Moe Dee, and Big Daddy Kane to a Los Angeles recording session. Eyebrows were raised.

There will never be another storyteller like Quincy JonesRead now

The uncompromising rappers certainly looked out of place among Great American Songbook luminaries as Ray Charles, Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan. “What do we do with this s—?” the four MCs wondered aloud after Jones played them the New Jack Swing title track for Back on the Block, Melle Mel recalled in the 2001 book Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. The maestro put them at ease. “Stretch yourself,” Jones said. “It’s about mind solution, not mind pollution, about keeping it real with the streets and true to yourself.”

For the Ice-T, godfather of West Coast gangsta rap, Jones’ co-sign was powerful. “Us being rappers, we [don’t] really get that full respect from the musical community,” Ice-T said during a 1990 premiere of the documentary Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones. “But now when somebody of Quincy’s caliber says, ‘Yo, rap is in there … all the suckers gotta leave that alone now.’ ”

Jones saw hip-hop as a full-blown, legit movement. In 1986, he gave his son, rap fanatic Quincy Jones III, a surprise birthday party at the Canastel’s Restaurant in Manhattan. Everyone from Run-D.M.C., LL Cool J, and the Beastie Boys to The Fat Boys, Roxanne Shante, Whodini and Kurtis Blow were in the house.

“By then it was clear — at least to some of us — that rap had made its mark in our culture,” Jones said, looking back. “It was our newest baby and it was here to stay.”

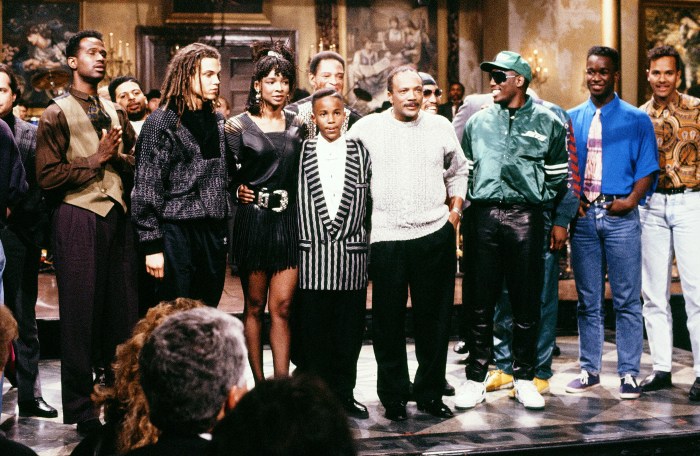

From left to right: Gospel group Take 6, Quincy Jones III, Siedah Garrett, Tevin Campbell, Al Jarreau, Quincy Jones, and Kool Moe Dee on Feb. 10, 1990.

From left to right: Gospel group Take 6, Quincy Jones III, Siedah Garrett, Tevin Campbell, Al Jarreau, Quincy Jones, and Kool Moe Dee on Feb. 10, 1990.

Raymond Bonar/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal

For Jones this was no brazen attempt at being the cool dad. When he saw his son’s wide-eyed reaction to meeting the tight-knit MCs it reminded him of the first time he met his bebop jazz heroes 35 years earlier, who, like the growing hip-hop scene, had faced opposition from community activists, politicians and law enforcement.

This was the golden age of hip-hop that produced such artists as Eric B. & Rakim, Too $hort, Salt-N-Pepa, Public Enemy, N.W.A., De La Soul and Queen Latifah. Rappers were going platinum and selling out arenas. Critics and fans hailed the youthful genre for its dynamic wordplay, unfiltered urban social commentary, and groundbreaking use of a production technique known as sampling. Rap’s detractors labeled it as best juvenile noise and at worst a danger to the community.

Jones, however, saw hip-hop’s future. And it transcended music. Impressed by the witty comedic rhymes and Middle America appeal of 21-year-old rapper Will Smith, one half of the double platinum Philadelphia duo Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince, Jones asked Smith to try out for the leading role in a new sitcom he was executive producing for NBC.

“Rap is not the primary focus,” Jones said of The Fresh Prince of Bel Air in an interview with The New York Times in 1990. “If you took the rap out, the premise wouldn’t fall apart. But rap gives you the purest street awareness.” The Fresh Prince of Bel Air was a ratings hit and started Smith on his way to becoming one of Hollywood’s most bankable movie stars.

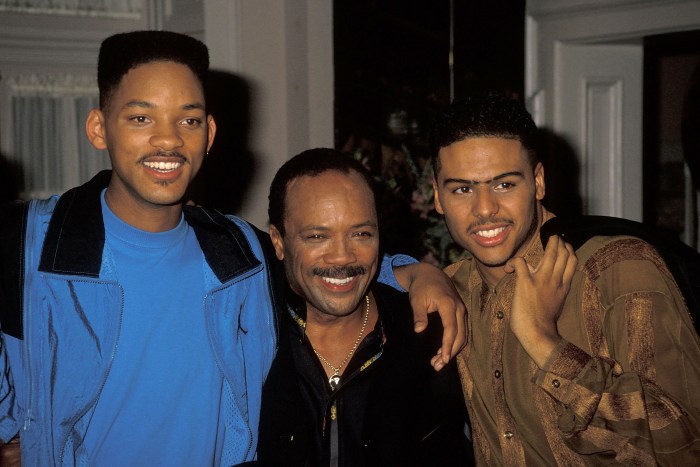

From left to right: Actor Will Smith, music/television producer Quincy Jones and singer Al B. Sure! on the set of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air on Oct. 20, 1990 at Columbia/Sunset Gower Studios in Hollywood, California.

From left to right: Actor Will Smith, music/television producer Quincy Jones and singer Al B. Sure! on the set of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air on Oct. 20, 1990 at Columbia/Sunset Gower Studios in Hollywood, California.

Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection

Jones wasn’t done. In 1993 he co-founded Vibe magazine, a glossy hip-hop publication that gave rappers such as Snoop Doggy Dogg, TLC, OutKast, Master P, The Notorious B.I.G., and Lil’ Kim the same serious, long-read gravitas as Rolling Stone did for white rockers in the 1970s. Jones’ relationship with his magazine’s biggest cover star, Tupac Shakur, however, was more complex.

When Shakur sat down for an interview with The Source magazine in 1993, he lashed out at Jones over his relationships with white women and having “f—ed-up kids.” “I wasn’t happy at first,” Jones told The New York Times Magazine in 2012. “He’d attacked me for having all these white wives. And my daughter Rashida, who was at Harvard, wrote a letter to The Source taking him apart.”

The situation eventually took a positive turn once Shakur met Jones’ daughter Kidada (the couple would later get engaged). “I remember one night I was dropping Rashida at Jerry’s delicatessen, and Tupac was talking to Kidada because he was falling in love with her then,” Jones recalled in The Times Magazine interview. “Like an idiot, I went over to him, put two arms on his shoulders and said, ‘Pac, we gotta sit down and talk, man.’ If he had had a gun, I would’ve been done. But we talked. He apologized. We became very close after that.”

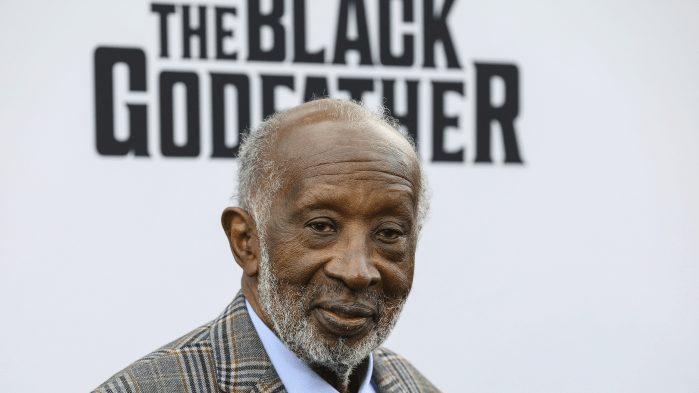

Clarence Avant was the guy who made sure Black stars got paidRead now

Clarence Avant was the guy who made sure Black stars got paidRead now

Jones remained one of hip-hop’s strongest defenders even in the aftermath of the deaths of its two brightest stars. He wrote an emotional 1997 Vibe editorial condemning the slayings of Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. as “senseless” and called out the East Coast vs. West Coast rap war as a “sad farce.” But when Jones was asked by a Los Angeles Times reporter about the negative criticism of hip-hop, he pushed back.

“To condemn hip-hop is to condemn two generations of our youth, and that’s a sweeping indictment that we can’t allow,” he said. “That hurts the situation more than helps.”

Over the years, Jones’ connection with hip-hop remained tight. He appeared in the 1997 music video for “Triumph” by the Wu-Tang Clan and wrote the score for 50 Cent’s 2005 movie Get Rich or Die Tryin’. Following his death, tributes poured in from hip-hop artists celebrating the man who embraced the culture.

“I’ve been away for a long time/I’m not only back but I’m here to rhyme/So bust a move, cause I am too/Back on the block, more training to do,” Jones rapped on the prologue to Back on the Block, which sold 3 million copies and won seven Grammy Awards, including album of the year in 1991. And Melle Mel, Ice-T, Kool Moe Dee, and Big Daddy Kane won a Grammy for best rap performance by a duo or group.

Mission accomplished.

Keith “Murph” Murphy is a senior editor at VIBE Magazine and frequent contributor at Billboard, AOL, and CBS Local. The veteran journalist has appeared on CNN, FOX News and A&E Biography and is also the author of the men’s lifestyle book “Manifest XO.”