The American Society of Human Genetics recently released a public apology for its participation in eugenics — a scientific movement in the early 1900s that discriminated against groups of people based on their ethnicity and physical features — and other instances of scientific harm.

The apology comes after the organization published a 27-page report detailing its past and its pivot toward better ethics in recent decades.

“This time of reckoning with history is overdue, but it forms the foundation for a brighter future,” ASHG President Brandan Lee said in a statement.

In the January report, “Facing our History — Building an Equitable Future Initiative,” the organization revealed that many of its early leaders advocated for or participated in eugenics. Some even held leadership positions in eugenics associations prior to joining ASHG, which was founded in 1948.

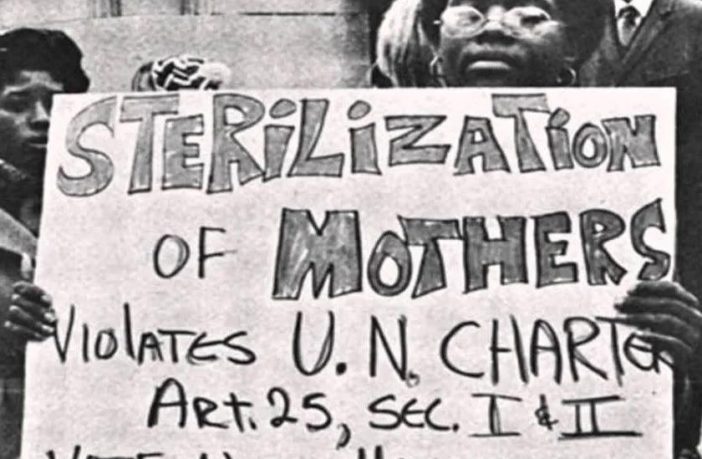

Through the 1970s, Black women living in poverty were forced and coerced into having hysterectomies or tubal ligations, preventing them from conceiving children.

Eugenics is founded on the immoral theory that deems groups of people as “unfit” human beings based on their genetics. Scientists — many of whom were white men — who adopted this idea used it to affirm preexisting prejudices about Black people and others held in society.

This led to the forced sterilization and genocide of Black people, immigrants, people with physical and mental disabilities, unmarried mothers, sex workers, those of lower economic status, and others.

Throughout the 20th century, 32 states adopted forced sterilization laws and participated in federally-funded sterilization programs.

“However, after World War II and the realization of how American eugenic policies inspired the atrocities of Nazi Germany, public popularity of eugenics collapsed,” the ASHG report states.

The collapse led to the founding of ASHG, according to the organization.

But eugenics has had a long-lasting impact on medical beliefs in the United States.

The “Mississippi Appendectomy” is one example of how eugenics attempted to limit the reproductive power of Black people.

Through the 1970s, Black women living in poverty were forced and coerced into having hysterectomies or tubal ligations, preventing them from conceiving children. In 1961, Fannie Lou Hamer, a civil rights activist from Mississippi, was given a non-consensual hysterectomy by a white doctor. The violation took place while she was undergoing surgery to remove a uterine tumor.

As recent as 2013, a report revealed that 148 female prisoners in California were sterilized between 2006 and 2010 without proper consent.

And in a 2016 survey, 40% of first and second-year medical students admitted to believing that “Black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.” Others reported believing that Black people are not as sensitive to pain as white people. As a result, the trainees were less likely to properly treat Black patients’ pain.

The report and its findings are painful and document a history that must be told and taught so we can prevent its resurgence.

BRANDAN LEE, AMERICAN SOCIETY OF HUMAN GENETICS PRESIDENT

As the science and medical industries face the aftermath of racist and prejudiced policy, ASGH has announced a plan for rectifying its contributions.

The organization is suspending the use of individual names for its professional awards that are affiliated with eugenics or other harms.

It also plans to prioritize equity in its scientific and training initiatives, sustain advocacy for research diversity, and continue building inclusivity of its leadership, to name a few goals.

“The report and its findings are painful and document a history that must be told and taught so we can prevent its resurgence,” Lee said.

“The human genetics research community is deeply committed to realizing a future in which all people benefit from this knowledge, and this promising research depends on full and equitable participation. By acknowledging our history and apologizing for wrongs, the Society seeks genuinely to form a stronger foundation for trust and inclusion.”