By Maya Pottiger,

Word In Black

Back in the 1990s, everyone was jealous of their classmate who had a phone in their room — doubly so if it was a private line. Otherwise, your parents could pick up in another room and listen in to your conversations, or at least know who you were talking to and when.

But with the dominance of cell phones, teens can live entire lives their parents don’t know about.

Adolescence is also a time when people are struggling with low self-esteem and body image issues, says Dr. Carletta S. Hurt, a certified school counselor in Washington, D.C. It’s a good breeding ground for manipulation.

“We have this person who says they love you, they care about you, they just want nice things for you,” Hurt says. “And then it turns into abuse.”

In her work as a school counselor, as well as with the American School Counselor Association, Hurt advocates for giving students vocabulary and knowledge, helping raise their awareness of abuse and manipulation.

Teens, of course, deal with cyberbullying. Particularly on Snapchat, where messages and photos delete almost instantly, cyberbullying is “dangerous because those images all disappear,” Murray says.

And teens are particularly susceptible to digital violence. They can be pressured to share passwords or targeted with mountains of texts. Everybody has a threshold, says Brian O’Connor, the vice president of public education at Futures Without Violence. And, due to their comfort with technology and the prevalence of it in their lives compared to trusted adults, they might not be able to recognize alarming behavior.

“Somebody texted you 12 or 13 times to ask you what you’re doing, where you’re going, who you’re with — it’s just not even a big deal. That can be alarming behavior,” O’Connor says. “Context really matters. It comes down to when you start to feel uncomfortable, or you feel threatened, you feel pressured, then something’s not okay.”

Another factor unique to teens is mutual violence. More than 40 percent of teens experience reciprocal violence, Murray says. While there isn’t concrete evidence to explain this, there are some hypotheses, Murray says, and it comes down to culture and media.

“Teenagers don’t quite grasp or understand all the aspects of violence yet at this age, so there is much more vulnerability toward it, much more acceptance of it,” Murray says. “Teens don’t quite know what is violence or what is acceptable, and they need us to teach them that.”

What the official numbers show — and what they don’t

Officially, about 1 in 3 teens in the United States experiences teen dating violence, according to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. And about 14 percent of students who dated in 2021 experienced some sort of teen dating violence — physical, sexual or both.

The CDC found that teen dating violence — physical, sexual or both — decreased from 2013 to 2021 and few differences were seen during COVID-19.

Female students experienced all types of teen dating violence at higher rates than male students, according to a 2021 CDC study.

“It’s unfortunate, being both Black and identifying as female increases the risk of teen dating violence,” says Angela Lee, director of love is respect, part of the National Domestic Violence Hotline.

And teen dating violence is particularly high among LGBTQ+ youth.

Between October 2022 and September 2023, love is respect logged 424,400 interactions. About half of those interactions provided demographic information and a quarter of them were Black.

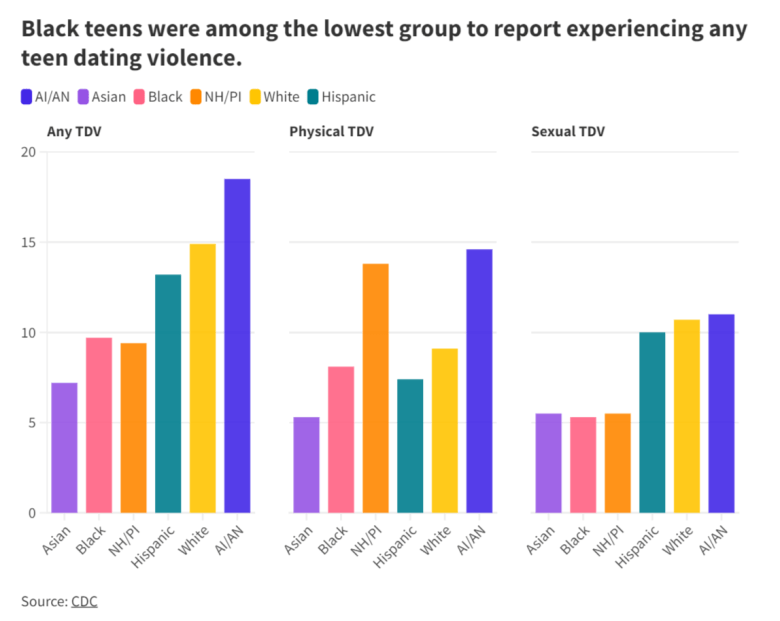

Rates varied across racial and ethnic groups. No matter the type of teen dating violence, Black students reported among the lowest levels.

But those are only the reported numbers.

“The statistics are really based on the disclosure rates, so youth may not feel as comfortable disclosing,” Murray says. “We anticipate those rates are way higher. And we do think that there is a disparity in Black youth that are impacted.”

Survivors of color, particularly in the Black community, face increased barriers to accessing support services, Lee says.

“Black youth are less likely to seek support, such as school counselors, due to concerns about confidentiality or a preference for seeking a more trusted support,” Lee says. “Even though Title IX is in place, have so many students and only one representative. We’ve heard their needs haven’t been met.”

We’ve actually been fed examples of unhealthy relationships since childhood.

Take “Beauty and the Beast” — we’re taught that, if you keep someone locked away in your home, they will eventually fall in love with you. Or “The Little Mermaid” — Ariel had to literally give up her voice for the prince to fall in love with her. More recently, Netflix’s “13 Reasons Why” received widespread backlash about the ways it depicted and romanticized suicide.

Gender violence is also glorified in the United States, Murray says, specifically citing the stereotype of the strong Black woman. What does that mean for a Black woman who is in a dating violence relationship? She might be looked down on for seeking help and going against what’s expected.

These media stereotypes lead audiences “to believe that unhealthy power dynamics are okay,” Lee says. And it gives them “a false sense of reality” that healthy relationships don’t exist in real life.

Murray referenced a study of movies and TV shows, which found two-thirds of all youth-based materials have violence of some sort.

As children’s brains develop, it’s hard for them to know what is and isn’t OK.

“What they see in front of them is what they accept as normal,” Murray says. “If you’re growing up watching TV shows without a conversation about it, you think being possessive of a partner and keeping them captive is romanticized and beautiful and normal.”

The role of school officials — and trusted adults

Schools have mandatory reporting laws, which require certain employees to report known or suspected cases of child abuse or neglect. But the laws vary by state and most states don’t mandate healthy relationship training for public schools.

But, as children spend most of their lives in schools, adults and counselors should have “some foundational knowledge” about how to recognize, intervene, and refer students to appropriate sources, Murray says.

This comes in many forms, like knowing the current dating language and developing comfortable relationships with students. This allows trusted adults to ask questions without limiting it to one conversation.

“Forcing adolescents to disclose” in one conversation “is actually causing more harm,” Murray says. “We encourage having these ongoing conversations and partnering with a trusted adult.”

And, when a student does come to you, it’s important to be culturally responsive, take them seriously and not dismiss the complaint, Lee says. Make them feel safe and comfortable.

From middle school through high school, there are “training wheels,” O’Connor says. It’s the responsibility of trusted adults to be guiding students to what safe and healthy relationships look like so they can go forward confidently.

Although no one situation is the same, teenagers look up to the adults in their lives, Lee says. Hurt echoed this, saying that families play a critical role in teen dating violence. It’s important to have honest conversations with teens about violence and where to draw the line.

“Some people suffer in silence. It’s not okay,” Hurt says. “Find someone you can trust, if nothing else, just to talk about it.”

If you or someone you know is being affected by intimate partner violence, please consider making an anonymous, confidential call to the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE (7233). Chat at http://thehotline.org | Text “START” to 88788. There are people waiting to help you heal 24/7/365.

This article was originally published by Word In Black.