By 2017, Tes Sobomehin Marshall was already known and respected as one of the better race directors in Atlanta. Since launching her company, runningnerds, in 2012, she has organized dozens of race events, ranging from friendly neighborhood 5Ks to challenging 10-milers and relay races. In her role, answering questions is a main part of the job description. But one query in particular made her create a solution.

“I was asked, ‘Have you ever thought about putting on a race for Black folks?’ ” She remembered the time in 2017 when she was a guest on the Real Runners of Atlanta podcast. “I don’t think they were singling me out, but there are so many conversations centered around all of the growth and the impact that we as Black runners have in the running community. So, we should do something that celebrates all the growth and the impact that we have.”

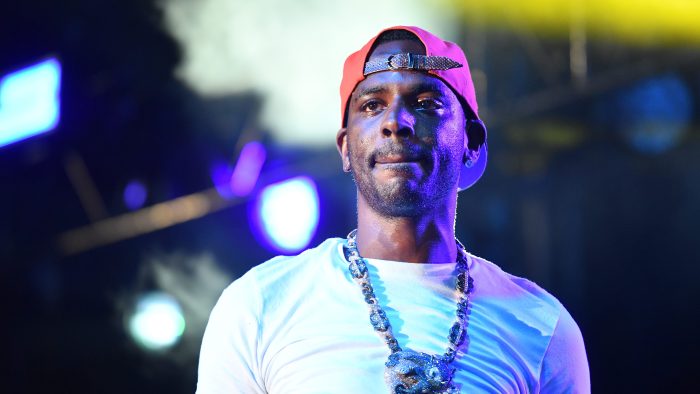

The Race founder Tes Sobomehin Marshall, addresses runners at the starting line on Oct. 7, 2023.

The Race

That celebration came in the form of The Race. The Race, which enters its seventh year in October, is a 5K (3.1 miles) and half-marathon (13.1 miles) designed to attract Black people to running. Marshall and a team of running enthusiasts created the first one by launching a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2017. Those who donated at least $75 to the $60,000 goal were automatically registered in the race in 2018. They collected more than $73,000 with many local running groups such as Black Girls Run, Black Men Run, Movers and Pacers and South Fulton Running Partners, the oldest Black running group in America, showing up to support the event.

“We came up with the concept of a Black-owned, Black-produced race that would support Black-owned businesses, neighborhoods, and charities,” Marshall said. She said that if the Kickstarter fundraiser had failed, she would not have gone through with it because it would’ve shown there was no support for the idea. “And we wanted the Black runners to be the ones that support it, sign up and be the main runners.”

This year, the runs are part of a four-day weekend of events that kicks off Thursday with a welcome event at the Black business hub and co-working space The Gathering Spot, where runners will receive a Black Business Crawl passport encouraging them to visit restaurants and shops supporting the event. On Friday, runners will meet at Impact Church, where the race starts and ends, for The Race Expo. Marshall said it wouldn’t be the typical kind where you just pick up a bib, but it would be more akin to a park festival with panels, yoga and vendors selling items such as shea butter and custom-made jewelry.

The main event 5K and half-marathon races are on Saturday morning. Runners are separated by their projected finish times and released in three waves: red, black and green. Pacers for various time goals will also be on the course. Marshall said that runners of all paces and races are welcome.

“We’re not afraid to say ‘for us, by us’ because it shouldn’t be offensive to anyone to hear that,” she said, adding there will also be music coupled with pre-race motivational speakers and warmup sessions. “When you get there, you’re going to see everybody. But at this race, if you’re a white, Asian runner or Hispanic runner, when you look to your right and left, you’re gonna be in the minority.”

The weekend ends Sunday when registered volunteers will gather for Community Impact Service Day, to do neighborhood clean ups, assemble care packages, gardening and voter canvassing. The Race then officially wraps with a day party at Monday Night Brewing Garage and a hip-hop and poetry show at City Winery. This year’s attendance will break 2,000 participants for the first time, with the 5K sold out weeks ago.

Runner Jetola Anderson-Blair runs down the Westside leg of the Atlanta Beltline during The Race on Oct. 1, 2022.

Runner Jetola Anderson-Blair runs down the Westside leg of the Atlanta Beltline during The Race on Oct. 1, 2022.

The Race

While community building and public health are core tenets of The Race, the routes also make a bold statement. Going through parts of the city’s predominantly Black south and west parts of town, The Race is unique in that it touches neighborhoods that most races in the city typically ignore. The Race’s half marathon route passes neighborhoods such as Oakland City, where Minnesota Timberwolves guard Anthony Edwards and rapper Lil Baby are from. Most of the city’s races, including popular ones such as the Peachtree Road Race, PNC Atlanta 10 Miler, Thanksgiving Day Half Marathon and Atlanta Marathon, mostly pass through downtown Atlanta, parts of the affluent (read: white) Buckhead and Midtown neighborhoods or sections in the final stages of gentrification. The Atlanta Marathon touches the outer boundaries of Southwest Atlanta and parts of neighborhoods where Clark Atlanta University and Spelman College are located, but only for a tiny part of the 26-mile course. On these routes, runners aren’t going to see much of the Black people or culture that the city is known for.

HBCU Alumni Alliance’s 5K participants cross the finish line to give students a head startRead now

HBCU Alumni Alliance’s 5K participants cross the finish line to give students a head startRead now

“In our first year, a lot of people asked me why aren’t we passing by all the landmarks,” Marshall said, voicing runner frustrations that The Race doesn’t pass picturesque locales such as Mercedes-Benz Stadium or Centennial Olympic Park. In past years, The Race volunteers have created promotional materials with historical facts about neighborhoods on the route. This is especially valuable given the fast pace at which demographics can change. “I’m like, well, that’s not what The Race was created for. It was created to run through our neighborhoods so that our people could see us running by and come out.”

Since 2021, Heather King (right) has paid homage to the “Pink Robe Lady (left),” who cheered runners passing by her house during the first The Race in 2018.

Since 2021, Heather King (right) has paid homage to the “Pink Robe Lady (left),” who cheered runners passing by her house during the first The Race in 2018.

Heather King

Heather King, who ran in the inaugural 2018 race, witnessed this impact firsthand.

“As we’re running through Sylvan Hills, we passed a house with a woman in a pink robe and rollers standing on the porch and she asked us why we were out running,” King said. “Once we told her why, she stayed out there and cheered for us for at least a good 30 minutes.”

King has become a fixture in the race. She dresses up as the “pink robe lady” to cheer for runners and hand out water and mimosas near the 2-mile marker to pay homage to the woman and the neighborhood.

The Race’s route through Black neighborhoods addresses what happens with races in other cities with large Black populations. The Detroit Free Press Marathon’s route goes through downtown Detroit and even into parts of Canada but doesn’t touch historically Black neighborhoods such as Bagley and Fitzgerald. The Cleveland Marathon has multiple twists and turns, turning its back neighborhoods such as Union-Miles, Lee-Harvard and the rest of the predominantly Black East Side.

There are other examples, but it’s not fair to accuse race directors of purposely avoiding Black parts of town only because of race. Organizing races includes fees for blocking streets and hiring police patrols. Race directors must also consider topography, the number of turns, and access to paths and parks while providing an enjoyable experience. Planning routes in certain areas may be easier to save the hassle.

Memphis rapper Young Dolph knew there was no love in the streets. His murder trial confirmed he was right.Read now

Memphis rapper Young Dolph knew there was no love in the streets. His murder trial confirmed he was right.Read now

Tony Reed, co-founder and executive director of the National Black Marathoners Association, suggests that the low number of Black people in business and logistics leads to decisions made without having Black neighborhoods in mind. He suggests that more Black runners become certified running coaches and become qualified as race directors so they can plan routes that go through their communities. This can lead to more Black people participating in the sport and enjoying its health benefits.

“Races don’t go through our neighborhoods, so we don’t see runners,” said Reed, a St. Louis native who lives in Dallas. He directed the 2023 documentary “We ARE Distance Runners: Untold Stories of African American Athletes.” He is on record as the first African American to complete the marathon “hat trick” of running 100 marathons, running a marathon in all 50 states and on all seven continents. “Even if they just go through part of a Black neighborhood, you’re gonna get more African Americans realizing that distance running is a sport that they can indeed pursue simply because they see a race going through their neighborhood.”

“If I’m running through the ’hood and I’m getting applause from somebody’s auntie or grandma saying, ‘go baby go,’ that encouragement hits different because it’s coming from home,” Stephen Love-Wade, founder of 6Run5, a Black-led run club in Nashville, Tennessee, said. “Plus, you never know who’s seeing you. It could be a kid who saw you run 15 years ago and said, ‘Man, I used to remember when they used to run through my neighborhood.’ Now that gives them inspiration.”

Marshall has already addressed this, so she doesn’t expect other race directors from different backgrounds to follow her lead.

Running club members join for a picture during a post-run celebration at The Race on Oct. 12, 2019.

Running club members join for a picture during a post-run celebration at The Race on Oct. 12, 2019.

The Race

“They would need a compelling reason to run a race event in our neighborhoods,” Marshall said, noting that Black neighborhoods don’t always have abundant resources to organize a successful race, such as venues, parking and desirable terrain. She said that not all parts of the neighborhoods in The Race are “as pretty as you would like them to be” and that the untapped areas provide plenty of options for more races and Black runner visibility. “Southwest Atlanta is vast. We could run 10 different marathon routes, but we still have not seen all of it.”

Atlanta is the home of The Race, a destination event for Black runners. Marshall said that roughly 40% of its registrants come from neighboring states, including Alabama, Florida, South Carolina and Tennessee, and from as far as California, New York, Ohio, Wisconsin and Texas. Last year, it officially became an international phenomenon. Twenty runners came from the United Kingdom via the Emancipated Run Crew in London.

Boston Celtics star Jaylen Brown unveils own brand and signature shoe ahead of 2024 NBA seasonRead now

Boston Celtics star Jaylen Brown unveils own brand and signature shoe ahead of 2024 NBA seasonRead now

“I’ve been running for over 25 years, and I’ve never in my life experienced anything like that,” Denise Stephenson, co-founder of Emancipated Run Crew, said. Stephenson created the group with her sister Jules and running partner Trojon Gordon to have a Black-led running experience in London. After hearing about The Race on a podcast, she came to Atlanta. “It felt like an adventure, crafted just for us.”

Jules Stephenson said, “We did a trip the year before to Lisbon, and had quite a few people who took their time confirming. But when we said we were going to Atlanta, they did not hesitate. Everybody booked their accommodations by the end of January and the race wasn’t until October.”

Traveling runners can stay in one of the two host hotels and get around via The Race’s official chauffeur, the Black-owned Platinum Luxury car service.

As plenty of runners have earned medals and podium placements in The Race, the memories matter as much as the miles. Some get more out of it than what they showed up for.

“One year, a high schooler in the 5K took the wrong turn and ended up doing the half marathon by accident,” Marshall said of the runner who didn’t realize his mistake until the eighth mile. “He asked somebody ‘when are we supposed to finish’ and they laughed, like, ‘honey, you’re on a half marathon course.’ The beautiful thing is that they stayed with him and helped him get through.”

Most people will tell you that Maurice Garland is a dude from Decatur, Georgia, who’s written some memorable stories about extraordinary people during some (mostly) unforgettable times for some legendary publications. Others will say they saw him talking on VH1 a couple of times or speaking at Spelman and Princeton. Many will mention that he started one of hip-hop’s first podcasts (Day 1 Radio), co-wrote a book about mixtapes (The Art Behind the Tape), and then edited Pimp C’s autobiography and J. Prince’s memoir. Now they are saying all he does is run marathons, do yoga and teach teenagers journalism and media-making at VOX ATL. None of them are wrong.