A new Hulu documentary has some people (not me) worried that what’s done in the dark may soon come to light. “Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told” from executive producers Jermaine Dupri and Uncle Luke is rummaging up old videos from what at one-time was THE party place to be (I know that looks like me on that Toyota Tundra shaking what my mama gave me, but it’s not).

The streaming platform has secured the rights to tell one of the most legendary stories in Black culture and history. “Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told,” will chronicle how the infamous event came to prominence. It will also document its swift demise.

According to the project’s synopsis, it “recounts the rise and fall of a small Atlanta HBCU picnic that exploded into an influential street party and spotlighted ATL as a major cultural stage,” raising the question: “Can the magic of Freaknik be brought back 40 years later?”

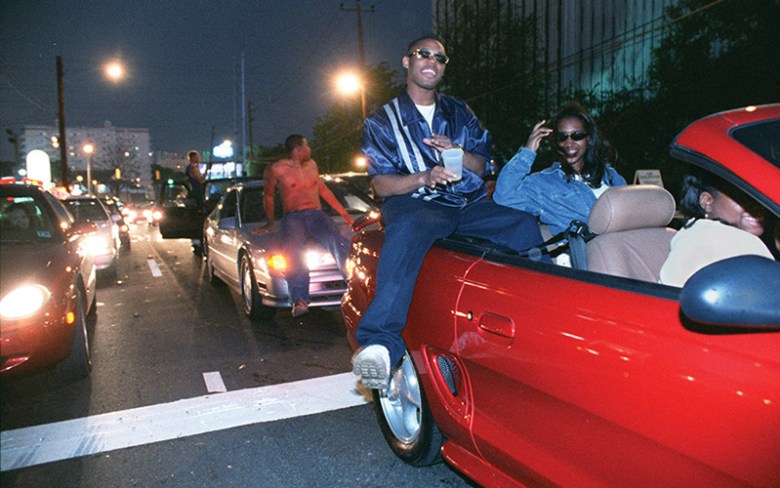

Crowds of kids, on foot and in cars, jam Marietta Street for Freaknik near the intersection of Peachtree Street as night begans to fall in downtown Atlanta Friday, April 19, 1996. Freaknik attracts 100,000 to 200,000 black college students for the annual street party. Credit: AP Photo/Atlanta Journal Constitution

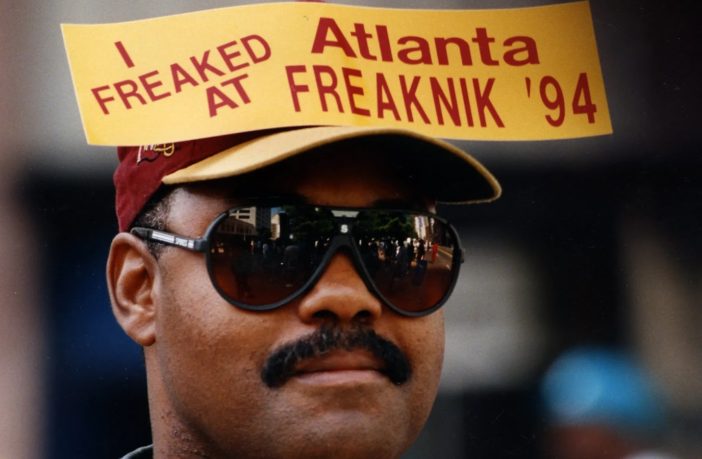

The yearly festival in Atlanta began in 1982 as a picnic for local college students and evolved into a meeting ground for black spring breakers and people of all ages around the nation. Originally spelled as Freaknic, it was conceived as an end-of-year party for students at historically Black colleges and universities. It became so popular that it turned into an annual event, was renamed, and HBCU students and non-students from all over the country started to flock to Atlanta in the spring to dance, have fun, and build community within the largely white spring break party scene. The event is remembered for today, inviting dance contests, concerts, parties, sporting events, rap sessions, job fairs, and more.

By 1998, the Associated Press reported Atlanta Committee for Black College Spring Break should no longer welcome Freaknik, citing “sexual assaults, violence against women, and public safety concerns.” Freaknik eventually stopped in 1999, with the city citing traffic problems. But it has remained a cultural moment that people remember fondly.

However, the desire for an event like Freaknik to return is ever-present. Many Atlanta organizations, event curators and rappers like 21 Savage have attempted to recreate the moment, but according to the OG’s there’s nothing quite like the real thing.

By the way, those of you in the Houston area who think you’re safe since you never made it to Freaknik… wait until that documentary on the Kappa Beach Party rolls out…

See the Gallery of Freaknik pics through the years.

INSERT GALLERY

Posing for a polaroid along Lee Street are, from left, Missy Moore, 16; Shaune’ Leonard, 20; and Toia Williams, 20. All three are from Hammond, Indiana. Gordon Green is the photographer. Shown on April 19, 1997. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP

Posing for a polaroid along Lee Street are, from left, Missy Moore, 16; Shaune’ Leonard, 20; and Toia Williams, 20. All three are from Hammond, Indiana. Gordon Green is the photographer. Shown on April 19, 1997. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP Members of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity from various school chapters do some strolling on April 18, 1997, at the Atlanta Universities campus on the first day of Freaknik. Credit: Rich Addicks / AP

Members of the Phi Beta Sigma fraternity from various school chapters do some strolling on April 18, 1997, at the Atlanta Universities campus on the first day of Freaknik. Credit: Rich Addicks / AP Hanging out and cruising was one of the staples of Freaknik. Revelers congregate on Roswell Road on Saturday April 19,1997. Credit: AP Photo/Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Chris Rank

Hanging out and cruising was one of the staples of Freaknik. Revelers congregate on Roswell Road on Saturday April 19,1997. Credit: AP Photo/Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Chris Rank The back of a minivan provides a good videotaping spot for these women from Missouri who were cruising the parking lot at Lenox Square on April 20, 1997, during Freaknik. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP

The back of a minivan provides a good videotaping spot for these women from Missouri who were cruising the parking lot at Lenox Square on April 20, 1997, during Freaknik. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP Shantrice Billingslea talks to some men in the parking lot of South DeKalb Mall on April 18, 1998. Right, Open container violations were not enforced during the Freaknik celebration as partygoers drove down Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in downtown Atlanta on April 23, 1994, while a security officer directed traffic. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP; Marlene Karas / ASSOCIATED PRESS

Shantrice Billingslea talks to some men in the parking lot of South DeKalb Mall on April 18, 1998. Right, Open container violations were not enforced during the Freaknik celebration as partygoers drove down Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in downtown Atlanta on April 23, 1994, while a security officer directed traffic. Credit: Jean Shifrin / AP; Marlene Karas / ASSOCIATED PRESS