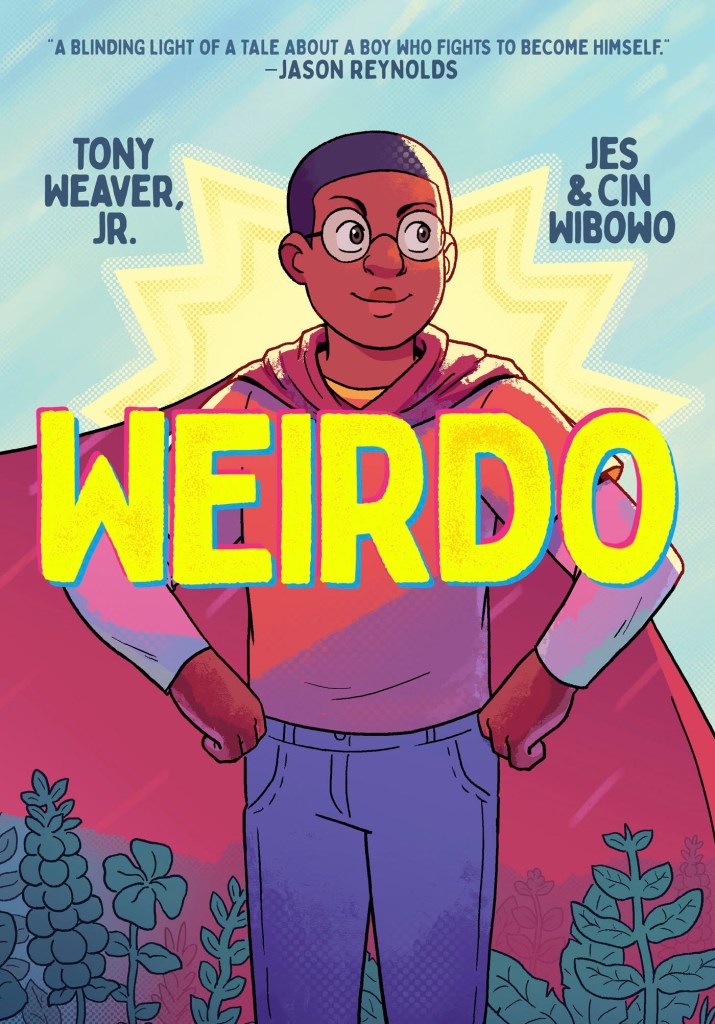

Tony Weaver signs copies of his recently released book, “Weirdo.” (Photo courtesy of Elon University)

By Aria Brent

AFRO Staff Writer

abrent@afro.com

Tony Weaver Jr., is shining a light on how adolescent Black men handle the taboo topics of bullying, mental health and suicide.

Inspired by his own story, Weaver’s book, “Weirdo,” follows a young on his own personal journey in handling the daily challenges of life.

The conversations sparked by the book are more relevant than ever, as a report titled “Still Ringing the Alarm,” shows that “In the 13-year period between 2007 and 2020, the suicide rate among Black youth ages 10–17 increased by 144 percent.”

According to the report, completed by The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Health and The Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, “Black boys ages 0–19 have more than twice the suicide rate compared to Black girls of their age group.” And while youth suicides overall are down, the suicide rate for Black minors increased between 2018 and 2022.

Although this is the young author’s first book, it’s already catching the attention of publishers, educators, parents and students alike. Weaver spoke with the AFRO about his experiences, his book and the importance of telling stories that allow Black youth to see themselves in their own, positive, quirky light.

AFRO: Why was it important for you to speak out and to give voice to the issues young men face?

Tony Weaver: I think that when we have conversations about youth mental health, very rarely do they explore it from the point of view of students of color– especially Black boys.

I think for Black boys, there’s this unique lens of toxic masculinity that’s placed on us–these kinds of unique types of pressure –more limitations and boundaries about how we must present, ways that we must police our thoughts, our physicality, our behavior. It was really important to me to tell a story from that point of view.

“Weirdo” is a book by Tony Weaver, offering advice to young Black men on mental health. (Photo courtesy of Tony Weaver website)

“Weirdo” is a book by Tony Weaver, offering advice to young Black men on mental health. (Photo courtesy of Tony Weaver website)

AFRO: What was the inspiration for the book ?

TW: “Weirdo” is a graphic novel memoir and it’s inspired directly by my personal life. When I sat down to write it, my idea was that my experiences could be helpful to someone. If there’s anything that I would say inspired it– it was the desire to help and be of support for young people that were struggling with their feelings and struggling to develop a healthy sense of self.

Graphic novels are a great way to engage people. But also, I think there’s something really powerful about the representation in “Weirdo.”

In the book, I go to a variety of different schools, but the school that I spend most of my time at is a private school where the kids are walking around in blazers, uniforms and things like that.

AFRO: The book is focused on mental health for students. When did you first start facing trouble as far as your mental health ? What were the first signs for you?

TW: I think there’s always been this feeling of “otherness” that I’ve had to deal with.

As long as I can remember, I’ve never quite felt like I fit in 100 percent. I think the steps that led me into a dark place in my mental health are tiny things that kids do every day: You compare yourself to other people, you aim for popularity, you try and shift who you are in an attempt to get the attention of the people that you feel like can give you value or worth. They’re all things that are very normal for an adolescent young person to be doing. But no one kind of pulls us to the side and gives us the rundown on how those activities can be harmful if unchecked and “Weirdo” is kind of intended to find kids at that point in their journey and help them understand that.

AFRO: What would you say to children in that awkward space who might be contemplating hurting themselves or are already engaging in some type of self harm?

TW: In “Weirdo,” what we say is “there’s always light on the other side.” I’ve heard that phrase in a lot of ways, where it feels like a platitude. It feels kind of corny– really cliche– but the book goes into a lot of detail around how to persevere, how to self assess your emotions and how to find community support when you feel like it’s not there.

An essential part of the human experience is that, at some point, we will all encounter darkness just by virtue of being alive.There will come a moment where there’s an obstacle we bump into that we feel like is much larger than us and will consume everything.

For me– it was my mental health, but it could be a conflict with a friend or family member, a rejection, a loss that you don’t know how to cope with. All of us are going to have to experience something that puts us in the dark, and when that darkness shows up, it tells us that it’s the only thing that we’ll ever know, that there’s no way out, that things will always be like this. But if we keep moving forward and find the people in our lives that are there to support us, there’s always a light on the other side.

I think one of the things I’m most proud of about “Weirdo” is how we’re able to go into detail and offer actionable tips to help students keep moving forward in a way that doesn’t feel corny or anything like that.

AFRO: How important is it for adults to see and do something about the signs and symptoms of depression ?

TW: I think the most difficult thing about it is that you need to prepare before the emotional difficulties happen. We should be working proactively to figure out how to have conversations about big emotions, how to have conversations about difficult topics before it’s time for those conversations. You don’t install a smoke detector after the fire is already burning—right? You take steps early.

Ultimately, it’s about communication. During adolescence, kids get really angsty. There’s a lot of drama, but communicating with them very early on that your love as a parent is unconditional and that you’re there and supportive for them, I think will be really helpful when they actually need that support.

AFRO: Can we talk a bit about your own suicide attempt?

TW: I was in the seventh grade.

I think my decision to attempt was rooted in a variety of different factors, lots of pressure. There’s lots of feelings of being alone and also feeling like things weren’t going to get better. I think it was pressure, difficult expectations, but also this idea that the situation was never going to improve.

I think on the other side of it, I wasn’t particularly happy. At the time, I tried something and it didn’t work. I came out on the other side like, “Dang, can’t even do that, right? That’s wild.”

AFRO: What role does social media play when it comes to sensitive topics like this?

TW: I think social media is a tool, and tools can be used for positive or negative purposes. On one hand, when I was a young person one of my greatest difficulties was that some of the kids that were bullying me would also post pictures of me and put things on social media where I was being picked on by kids that I didn’t even know. How am I supposed to defend myself in that context? This repeats itself a little bit, because if you put the picture online on Monday, someone else is going to find it on Tuesday or Wednesday. On the flip side, as an adult now I leverage social media in order to support youth mental health, to talk to young people where they provide actionable tools for people that might not be able to find those resources or support elsewhere. What matters is how we use it and how we teach kids to use it.

AFRO: What was your recovery journey like ?

TW: I had a cousin who was going to the same school as me and she noticed that something was going on with me. She told her dad, her dad called my dad and my dad came and pulled me out of the school that I was in. My parents got me into therapy and over the course of the book we see me in therapy sessions, interrogating some of these ideas and feelings.

We talk about therapy a lot as if you kind of just sprinkle some therapy on somebody and they’re fine. But there are things that need to be worked through and in the book, we really explore from the perspective of a young person.

When you’ve locked yourself into this kind of negative narrative about your capabilities and what people think of you, how do you undo that? Therapy was a gradual process.

I went to a school in Washington, D.C., and after I finished my keynote it was time for the Q and A, a kid raised his hand and he asked, “How do you know when you’re fully healed?” And what I communicated to him was that you never really know.

Healing isn’t always a linear thing and I think that for something as dynamic as emotions, rather than looking at healing as this destination, healing is a practice. Healing is something that you do every day. It’s something that you commit time to every day. It’s something that shows up in your habits and thinking about it like that just allows you to naturally move at your own pace.