This is the second installment in a series about Sam P.K. Collins’ travels to Dakar, Senegal.

Not long after publishing the first installment of my Dakar, Senegal series, my phone and that of my significant other disappeared from our hotel room.

Last I recall, we were watching YouTube documentaries on her phone in the wee hours of the morning. Once she fell asleep and my eyelids grew heavy, I threw our phones on the bed and turned to my side in preparation for a good sleep.

When I woke up out of my slumber four hours later, I searched the bed for my phone, as I always do as a force of habit. Unfortunately, we never found my phone or hers. They weren’t on our bed where we left it. Neither were they underneath the bed or anywhere else in the room. During our search, I found that the balcony door, which was closed earlier in the night, was wide open.

I’ll let you, the reader, put two and two together.

This situation became somewhat of a setback in what has otherwise been a relaxing and eye-opening experience. However, as I repeated in my inner-D.C. voice throughout that day, someone out there around the hotel caught us loafin’, even though we had taken extreme precautions to not be on the receiving end of a scheme.

The hotel, the name of which I won’t reveal, was located in the middle of a secluded community, surrounded by apartments and businesses. It was within 10 minutes of the main road where my significant other and I walked to catch a taxi. Every day, men, women and children sat outside of their houses talking among one another, lighting incense, engaging in their daily Muslim prayers, and scrolling through their phones as we walked along the beaten path to get to that main street.

It was like any neighborhood I’ve walked through in D.C., and any other majority-Black city I’ve visited in the United States. Although I initially had some apprehension about walking back and forth through the various cuts and alleys leading to our hotel, I eventually chalked that up to the physiological reaction to growing in the D.C. of the 1990s and early 2000s.

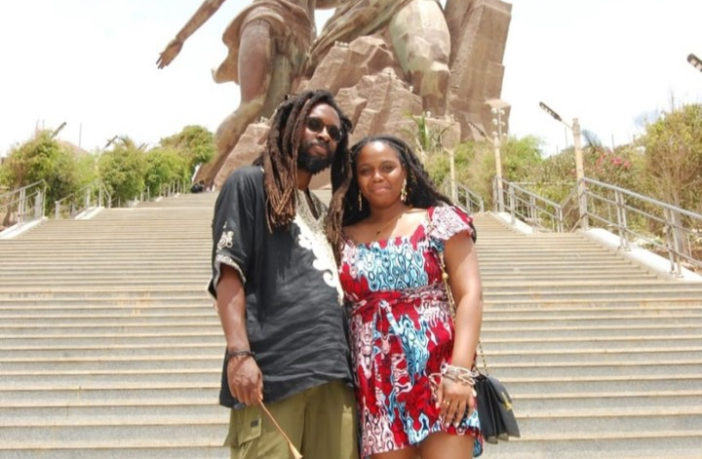

In the days preceding and following that incident, my significant other and I would often walk the streets of Ngor, Dakar — along what’s called the Airport Route — and the Alimades where all the popular nightclubs are located, all in search of a good time.

Indeed, we found several places to have a good time. We also found panhandlers of different ages.

In Dakar, panhandling is an industry and family activity. Sometimes, groups of children may walk up to you with buckets in hand, motioning their hand toward their face in request of some money. Other times, it might be an elderly woman in a Muslim shawl or a man with a physical disability.

In other instances, as I had witnessed firsthand, a little girl might leave her mother and siblings on the curb to chase someone and pull them by the arm in the hopes that they provide some funds.

I’m not going to lie. When that little girl did that, the D.C. in me turned around quickly and yelled, not seeing who I was yelling at at that moment. When I looked to my left and looked down to see the little girl, I grew embarrassed and apologized repeatedly as she grew startled.

Minutes later, I circled back to break the young sister off with a 500 CFA, what’s almost a U.S. dollar.

These moments, and other moments from Ngor, continued to stay with me throughout my stay. When we had no funds to give children, we often doled out snacks and water. Other times, we apologized when we had nothing, all to no avail. The young children, relentless in their pursuit of sustenance, kept asking us for whatever we had.

In recent years, the Senegalese government has made great strides to mandate that children up until their late teens be enrolled in free public schools. Even so, a significant portion of young people find themselves in parallel Islamic schools where they are often responsible for raising funds for their teachers.

Students who navigate Senegal’s public education system often experience more difficulty in passing through the secondary tertiary levels if they don’t make the mark on their exams. Those who don’t fulfill requirements to pass through the next level are funneled off into trades that might not be lucrative.

This situation bears a striking similarity to what our Black children experience in the U.S. In the absence of quality education and a social safety net, people are left to participate in alternative economic systems and revert to habits that destroy people, or at the very least inconvenience them, as had been the case for my significant other and me when our phones disappeared.

In the ongoing fight for African liberation, we must be cognizant that we’re in the period of class struggle where the enemies of progress aren’t only Europeans, but those with significant economic means who perpetuate systems that exploit families, and most especially children.

I wouldn’t say that I’m in favor of socialism or capitalism. I’m not entirely sure if what I’m endorsing fits along that spectrum. However, as a 21st-century Garveyite, I don’t shy away from my insistence that African people develop their own industries so they can do for themselves in a society where people are inherently selfish.

Seeing what I’ve seen in Senegal has made me a bit more skeptical of government’s ability to ensure that people from all walks of life have access to the bare essentials that will give them a leg up in life. It’s not about creating a welfare society. It’s about creating a situation where people are able to live freely and without worry about their next meal.

Our failure to reach this level in our development is indicative of a collective failure on our part to share natural resources. That failure starts at the top with politicians who collude with multinational corporations and mavens of industry to perpetuate inequity and keep a group of people in a vicious cycle of poverty.

As I wrap up this entry, I think back to conversations I had with well-meaning comrades before traveling to Senegal where I was warned about becoming a hostage or the target of a government plot to stunt our efforts to foster Pan-African unity. To them, I say who needs intelligence agencies and government leaders to sabotage our activities when the conditions that have been put in place are not only keeping people mired in poverty, but ensuring that we turn against each other and not toward our collective fight for liberation.