Source: Frazao Studio Latino / Getty

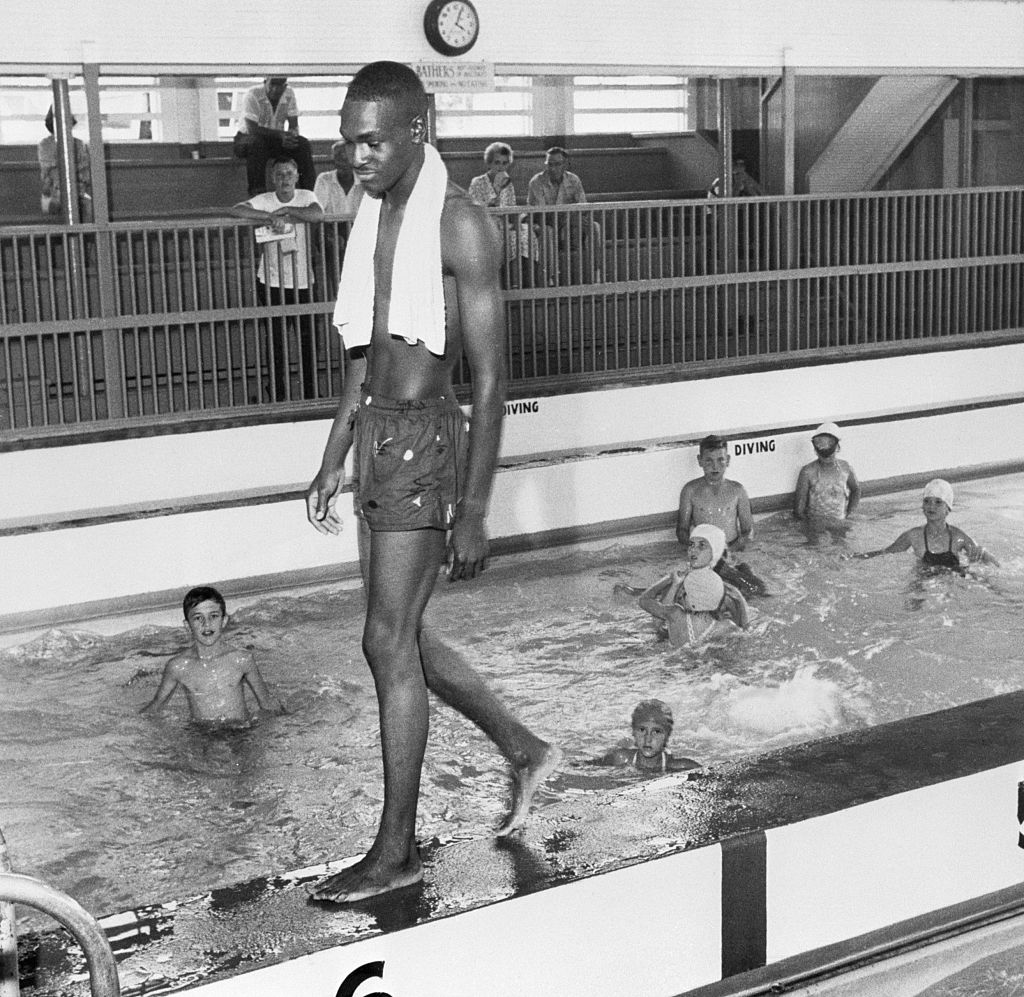

Water has often been a symbol of freedom, tranquility and recreation. However, for Black communities, water is connected to a troubled history of barriers, stemming from systemic racism, exclusion and limited access to pools and swimming education.

According to a 2017 study conducted by the USA Swimming Foundation, 70 percent of African Americans do not know how to swim. The startling number is intertwined with America’s dark history of segregation. When recreational swimming became popular in the 1920s and ’30s, segregation prevented many Black families from learning the vital skill as a large portion of public pools were placed in white neighborhoods.

The History Of American Swimming Pools.

Segregation perpetuated the swimming stereotype in the Black community. Public pools and beaches were segregated, with Black communities often denied entry or relegated to poorly maintained facilities, if any at all. Denied access to proper swimming education, many Black individuals never had the opportunity to learn how to swim which perpetuated a cycle of limited water safety knowledge within the community.

Parents Never Learned.

Moreover, the lack of swimming facilities and educational resources in predominantly Black neighborhoods contributed to a vicious cycle of fear that would trickle down to parents and generations of Black families. Without access to pools and swimming programs, the chances of learning swimming skills were slim. As a result, stereotypes and myths about Black people’s inability to swim persisted.

“It is because of discrimination and segregation that swimming never became a part of African-American recreational culture,” Contested Waters author Jeff Wilts told the Dallas News.

The Civil Rights Movement brought about legislative change, but the impact on swimming disparities wasn’t immediate. Even after legal desegregation, socioeconomic factors continued to hinder access. Private pools and clubs often remained inaccessible due to high membership fees, expensive programs or implicit discrimination and racism, further limiting opportunities for Black individuals to learn how to swim.

A 2022 Northwestern Medicine survey conducted in Chicago reported that over 26 percent of Black parents never learned to swim. However, that number was slightly small in comparison to 32 percent of Latin parents, who reported they had never learned to swim. Around 46 percent and 47 percent of Black and Latino respondents said they had never enrolled their children in swimming classes compared to parents of white children (72 percent).

Source: Bettmann / Getty

Black youth have a high risk of drowning.

Years of segregation at public pools and increased privatization of swimming lessons have left many Black Americans fearful of the water. Sadly, those barriers are beginning to have long-term consequences on the generation of today. According to the YMCA, 64 percent of Black American children cannot swim. Black children are also three times more likely to die from drowning than other races.

“To improve swimming abilities in Black and Latine communities, we need to address swim comfort and skills for both parents and their children,” Michelle Macy, an author behind the Northwestern study said. “Expanding access to pools and affordable, culturally tailored water-safety programs are critically important strategies to help eliminate racial disparities in child drownings.”

There is a lack of representation in professional swimming sports, but there are a number of trailblazers working to bring change to the world of swimming.

In recent years, efforts have been made to break this cycle of exclusion. Community organizations, educational programs, and initiatives focused on water safety and swimming education have emerged, aiming to provide access and opportunities for marginalized communities to learn how to swim.

In 2020, British swimmer Alice Dearing became the first Black British woman to compete at the Olympics. The 26-year-old athlete is doing her part to bring inclusion and representation to the industry. The open-water champion is also the founder of the Black Swimming Association which advocates for diversity in aquatics.

Swimming caps have historically posed challenges for athletes of color. Traditional swim caps are often smaller and tailored for individuals with thinner hair, making it tough for swimmers with natural hairstyles like locs, braids, or kinky curls to shield their hair from water and chlorine damage. The absence of suitable swim gear has pushed some swimmers of color to the brink of leaving the professional sport.

Launched in 2017, SOUL CAP is the brainchild of Toks Ahmed and Michael Chapman. The duo created the swim cap to accommodate Black swimmers and individuals with thick and voluminous hair. The company was delivered a major setback in 2021 after FINA banned the use of their inclusive swim caps at competitions.

Initially, the association argued that athletes competing at the Olympics and other international competitions “never used” and were not required to wear “caps of such size and configuration.” Thankfully, FINA dropped the ban in 2022.

“So many people in my family did not learn how to swim because, you know, their hair wouldn’t stay straight, or it’d be too unruly, or whatever,” Division 1 swimmer Erin Adams told the New York Times about FINA’s discriminatory ban.

“So I always had braids in my hair when I was younger, and I don’t know why it just didn’t bother me that my hair was different than my peers in swimming. We’re always policed on what we can wear and what our bodies are looking like, and what our hair is looking like. They’re just trying to make it difficult for us to have ease when participating.”