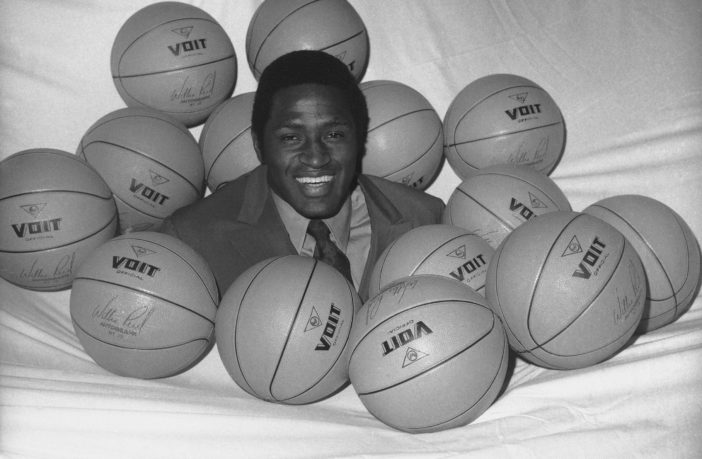

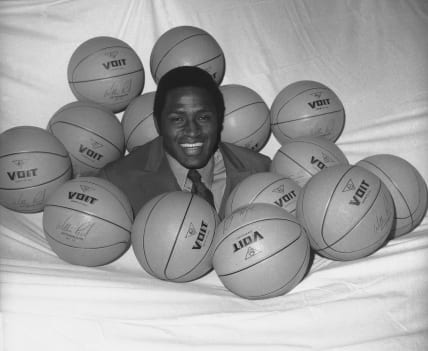

New York Knicks NBA player Willis Reed is surrounded by basketballs in New York, May 14, 1970, where he received his award as the NBAs Most Valuable Player. Willis Reed, who dramatically emerged from the locker room minutes before Game 7 of the 1970 NBA Finals to spark the New York Knicks to their first championship and create one of sports’ most enduring examples of playing through pain, died Tuesday, March 21, 2023. (AP Photo/Anthony Camerano, File)

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

As a youngster in Brooklyn, my love affair with the NBA and the New York Knicks hadn’t kicked in yet when Willis Reed created one of sports’ most iconic moments. I was still getting used to white classmates in a white neighborhood after being put on a school bus for second grade. But I eventually grew to realize why May 8, 1970 stirred so many emotions, in the city and elsewhere.

That’s when Reed limped from the tunnel onto the court at Madison Square Garden for Game seven of the NBA Finals.

Hollywood draws inspiration from such scenes, a crowd erupting as the injured star unexpectedly emerges from the locker room for a must-win game. The Los Angeles Lakers were shook and never recovered. A legend was born, and Reed, who died Tuesday at age 80, was cemented in sports lore forever.

Not bad for a country boy from Hico, La., which he once described as so small, it doesn’t have a population.

Reed went from Grambling State University to Broadway’s bright lights, etching his name in history with grace and class. It helped that he played in the nation’s largest media market, which magnifies most any story. And it helped that he hit his first two jumpers in storybook fashion (0-for-3 the rest of the game), which intensified the emotional jolt. It fueled the Knicks to win their first NBA title behind 36 points and 19 assists from Walt “Clyde” Frazier.

But it’s called “The Willis Reed Game” for a reason, not for his paltry four points and three rebounds. “There isn’t a day in my life that people don’t remind me of that game,” Reed told the New York Times in 1990, around the celebratory 20th anniversary.

Knicks fans have celebrated little since the night Reed limped out. New York won its second title in 1973 and lost its only other Finals appearances (1994 and 1999). The team hasn’t been to the conference finals since 2000. It’s a marquee franchise with nothing to brag about of late.

But we’ll always have that instance when broadcaster Jack Twyman uttered his historic line: “I think we see Willis coming out.”

Considering what was necessary for that to occur, not many players today would’ve made the trek. In Game 5, Reed suffered a torn muscle in his right leg, which left him unavailable for Game 6. There was only one way to play in Game 7, and he took it, a massive dose of painkillers.

“It was a big needle,” he recalled. “I saw that needle and said, ‘Holy cow.’ And I just held on. I think I suffered more from the needle than the injury.”

Painkillers are controversial in sports, especially in the NFL. We don’t know when a team is compromising players’ health for the sake of winning, encouraging them to take injections and downplaying the risks. Athletes apply their own pressure, too, on themselves and their peers; Reed’s teammates asked if he could ignore the pain for their common cause.

“They told me if I could just give them 20 minutes, we’re going to win it all tonight,” he recalled. “… It was one game for the championship, and as the captain, I had to do what I could do.”

Those were the days before load management and $40 million annual salaries before players spent goo-gobs on their bodies in nutrition, maintenance and recovery. It was also when more former HBCU players could be found throughout the league. Dick Barnett (Tennessee State) starred alongside Reed in 1970 and was joined by Earl Monroe (Winston-Salem State) for the Knicks title in 1973.

Reed averaged 26 points and 21 rebounds as a senior at Grambling before New York selected him in the second round of the 1964 draft. He spent his entire playing career with the organization and later spent several years as an executive with the New Jersey Nets, including NBA Finals appearances in 2002 and 2003.

The Game 7 appearance came to define him, but Reed was more than an inspirational figure, averaging 18.7 points and 12.9 rebounds for his career. He won Rookie of the Year in 1965 and Most Valuable Player in 1970. He also was a seven-time All-Star who won the Finals MVP in both championship seasons.

“Willis Reed was the ultimate team player and consummate leader,” NBA commissioner Adam Silver said in a statement. “My earliest and fondest memories of NBA basketball are of watching Willis, who embodied the winning spirit that defined the New York Knicks’ championship teams in the early 1970s.”

That Louisiana country boy repped the Big Apple like few other players while giving fans everywhere an unforgettable moment. He also planted seeds of my budding interests, becoming part of who I’ve grown to be.

I wasn’t at Madison Square Garden on May 8, 1970. But I feel like I was there, with everyone else, cheering for Reed and our beloved Knicks. He displayed his superpower that night.

We could use a lot more of it today.

Deron Snyder, from Brooklyn, is an award-winning columnist who lives near D.C. and pledged Alpha at HU-You Know! He’s reaching high, lying low, moving on, pushing off, keeping up, and throwing down. Got it? Get more at blackdoorventures.com/deron.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!