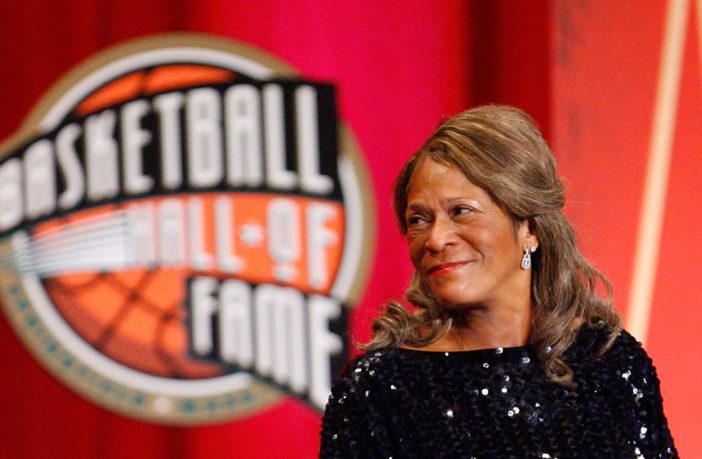

C. Vivian Stringer is inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame during an induction ceremony on September 11, 2009 in Springfield, Massachusetts. (Photo by Jim Rogash/Getty Images)

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

Dawn Staley has been a boss on the sideline for 23 seasons and shows no sign of slowing as top-seeded South Carolina opens defense of its NCAA women’s basketball title on Friday. But as the only Black basketball coach with two Division I titles in women’s (or men’s) hoops, she always pays homage to the pioneer who won none.

“The strength of your shoulders allowed us to stand tall,” Staley posted on Twitter when C. Vivian Stringer retired last season. “We will forever keep your legacy in our hearts. Thank you, Coach Stringer.”

Stringer ended her illustrious career in April 2022 after 50 years and 1,055 wins as a head coach. She once was quite a fixture at this time of year, taking her teams to 25 of the first 31 tournaments from 1982 to 2012. The Hall of Famer’s journey began with a highly improbable run that remains a precedent.

The NCAA didn’t create the women’s tournament until 1982, more than 40 years after the men’s version. Stringer and her team at then-Cheyney State College (now Cheyney University) wasted little time making a statement on Black achievement against all odds: They advanced all the way to the finals before losing to Louisiana Tech.

No HBCU before or since has reached the Final Four, let alone the final game.

It didn’t matter that Stringer was a full-time professor who coached as an unpaid volunteer. It didn’t matter that Cheyney had no money for athletic scholarships or a team bus. It didn’t matter that the players had substandard facilities and laundered their own uniforms.

“We were poor, but we never held that against us,” Stringer told Sports Illustrated. “We never felt sorry for us. Because we didn’t have anything, we feared no one, and I think that’s the greatest motivation in the world.”

Rutgers coach C. Vivian Stringer gives instructions to Matee Ajavon in the second half of a regional semifinal of the NCAA women’s basketball tournament in Greensboro, N.C., Saturday, March 24, 2007. (AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain, File)

Rutgers coach C. Vivian Stringer gives instructions to Matee Ajavon in the second half of a regional semifinal of the NCAA women’s basketball tournament in Greensboro, N.C., Saturday, March 24, 2007. (AP Photo/Mary Ann Chastain, File)

Never scared, the Lady Wolves regularly practiced against Cheyney’s men’s team (coached by legend John Chaney) and rose to No. 2 in the country. Let that sink in for a moment because it’s hard to fathom. This tiny HBCU, with a shoestring budget and eight high school All-Americans, played in Division II but ranked among the nation’s biggest and best hoops programs. They slayed a who’s who of power-conference schools — including Auburn, North Carolina State and Kansas State — en route to the title game.

Organizers thought so little of Cheyney’s chances at the Final Four, the commemorative T-shirt pictured just three representatives. The Lady Wolves were still being slept on, but they slapped skeptics awake by beating Maryland. It was Cheyney’s 23rd consecutive win.

“They really were pioneers in a lot of ways,” UConn coach Geno Auriemma said in an ESPN documentary. “For a small school like that with no resources, to show other programs around the country: It’s not about the money; it’s not about the facilities. It’s about the people.”

A coal miner’s daughter, Stringer was accustomed to exceeding other folks’ expectations. She sued her high school and won a spot on the cheerleading squad after initially being denied because she was Black. Cheyney won 83% of its games in her 12 seasons (251-51). Upon leaving for Iowa State in 1983, she built a powerhouse that helped propel women’s basketball to new levels, reaching the Final Four again in 1993.

More success followed at Rutgers, including two Final Fours and a controversy over racist remarks from shock jock Don Imus in 2007. The incident garnered more national attention in a week than her 36 years as a coach. “We have all been physically, mentally and emotionally spent, so hurt by the remarks that were uttered by Mr. Imus,” she told NPR. “But no one can make you feel inferior unless you allow them. We can’t let other people steal our joy. We’ve always understood that for a long, long time.”

Imus’ “nappy-headed hoes” comment was doubly painful because it followed Rutgers’ loss against Tennessee in the national title game. Stringer never got over the hump in 28 NCAA tournament appearances but became the first coach to take a trio of schools to the Final Four. She was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2009 and the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2001; she’s fifth in all-time victories and the first Black coach with over 1,000 wins.

Today, Staley is the standard bearer among Black women coaches, a three-time National Coach of the Year honoree whose undefeated Gamecocks are poised for a repeat title. We can draw a direct line from Stringer to Staley, who was a toddler in Philadelphia when Cheyney was becoming a powerhouse 30 miles away.

“I’m so proud of what (my players) represented for all of us,” Stringer said in the ESPN doc. “Little did we know how much of an impact it was going to make on so many people throughout our lives.”

And the beat goes on.

Deron Snyder, from Brooklyn, is an award-winning columnist who lives near D.C. and pledged Alpha at HU-You Know! He’s reaching high, lying low, moving on, pushing off, keeping up, and throwing down. Got it? Get more at blackdoorventures.com/deron.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!